In this article Lorena Gonzalez and Jes Olvera from the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights highlight some of the key challenges they have faced in their work trying to give voice to children from minoritsed communities (whose voices have often been little-heard) and explore why this dictates taking a justice-centered approach to philanthropy; which asks funders to think in terms of solidarity, rather than charity.

By Lorena Gonzalez & Jes Olvera

22nd May 2023

How does philanthropy understand and respond to social inequity?

This is a question many have been grappling with within the immigrant rights movement; and even more so within the immigrant children’s rights movement, in which we work. It has led us to wonder how funders can better engage with nonprofits focused on addressing social inequities through an equity and justice-centered lens and what must change about the culture of philanthropy in order for this to happen.

Back in 2019, amid the chaos of the Trump administration’s devastating zero-tolerance policy –a deliberate and government-sanctioned effort to rip thousands of children apart from their parents at the US’s southern border– donations to nonprofits directly serving immigrant children spiked. The Young Center was among them. We spoke with funders across the country about our work advocating for the rights of unaccompanied children, including those who had been separated from their families and our efforts to ensure they were reunified. Everyone we spoke with agreed the government’s intentional cruelty was appalling and that families deserved to stay together. Yet, even within these conversations, elements of saviorism and a potentially problematic understanding of philanthropy as synonymous with charity also surfaced.

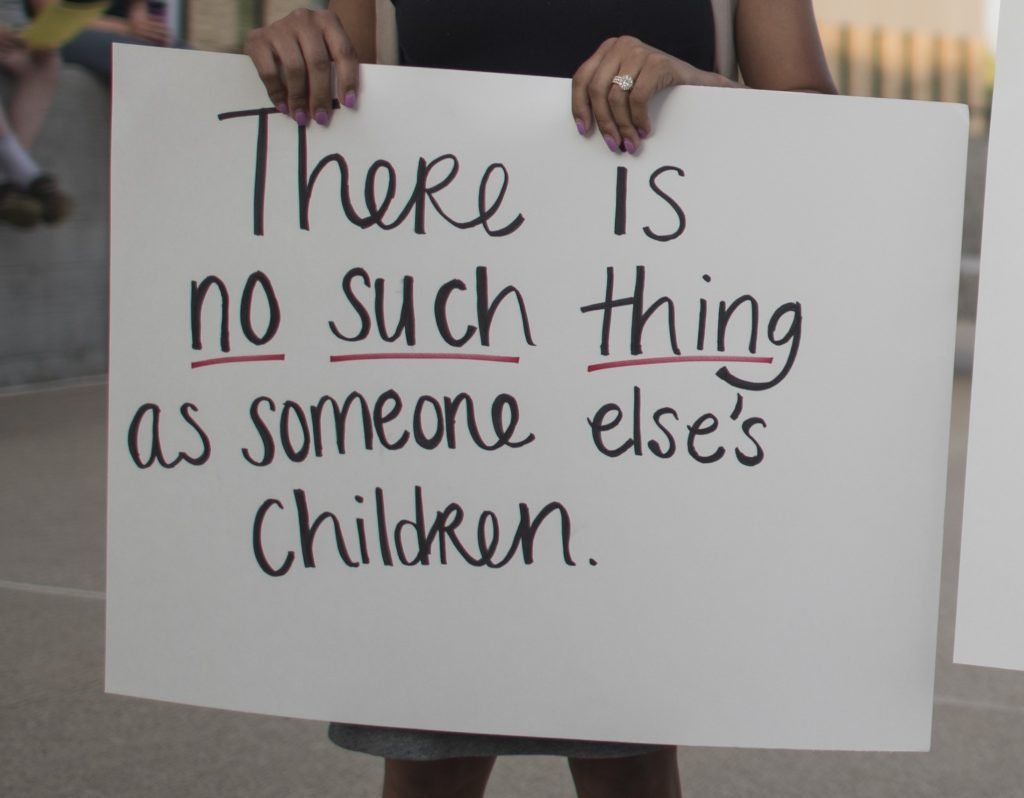

There is no denying that funder support is, and long has been, instrumental to sustaining the life-changing work so many nonprofits are spearheading across the globe. Yet, a charity-based culture of philanthropy reinforces a harmful “us” vs. “them” hierarchy between funders and impacted communities and perpetuates a false ideology that those who give – largely white individual donors or white-led corporate and institutional funders– are operating from a superior position where their donations are gifts to those “less fortunate” and, in the case of immigrant children, can help “rescue Black and Brown kids” from their conditions.

While it is certainly true that immigrant children may need particular support due to the unique and disproportionate harms they face as a result of our country’s immigration system, there is a real danger that a philanthropy-as-charity framework fails to consider their autonomy, voices, and experiences when addressing those harms. Given that those who are closest to the pain are almost always closest to the solutions too, there is a huge opportunity cost to this. That is why funders must dedicate the time to understand children’s journeys in their own words. They must take the initiative to learn about histories other than their own and the circumstances that immigrant communities face before, during, and after their journeys to the U.S. And, perhaps most importantly, they must ask: “How can I be of most help to you?” rather than assuming that their way of helping is the way directly impacted communities need.

Thus, philanthropy through an equity and justice-centered lens requires a paradigm shift whereby donors see themselves not as givers but as partners, allies, and actors who should leverage their resources in ways that reflect the actual needs and priorities of directly impacted communities.

In short, philanthropy must be about solidarity not charity. Marshall Ganz, a leader in community organizing who formerly fought alongside the labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez once said:

“Charity asks, ‘what’s wrong, how can I help?’ Justice asks, ‘why is it happening and how can I change it? ‘And that’s when people get uncomfortable. Because it is often the case that these people over here have less, because these people over here have more. And when we try to change that, there’s resistance & there’s conflict and struggle.”

At the Young Center, to try and overcome these sorts of challenges, we have embraced a community-centric culture of philanthropy that we believe honors our values of equity and justice and our mission of advancing the rights of immigrant children. This culture not only requires nonprofits to be deliberate about which grants they apply for and which donors and funders they work with and accept donations from; it also demands that donors and funders see themselves not as just givers but as partners who are equally a part of the society we aspire to make safer for us all. Community Centric Fundraising and philanthropy is about learning from those who are most directly impacted by societal inequities and committing to the long-term ambition of eliminating societal harms that have denied, and continue to deny, certain communities their fundamental rights.

That is why in our work alongside unaccompanied and separated immigrant children, we strive to create a culture of philanthropy where funders reject the notion of “saving” immigrant children and embrace instead the idea of becoming agents of social change and champions who are committed to learning from immigrant children, listening to them, honoring their expressed wishes and needs, and fighting shoulder to shoulder to protect their rights, safety, and well-being. And we need other stakeholders to join us on this journey, as at the end of the day it will depend on all of us, including funders, to ensure that the cruelty of family separation never happens again.