We are often told that human nature is selfish and that life is all about competition and struggle. Yet around the world every day, millions of acts of generosity take place: from mega-donations to fund universities and museums, to simple (but no less important) acts of individual kindness from those with little or no money to give.

Is something overcoming our innate selfishness and making us think of others before ourselves? Or is the truth that we are actually hard-wired to be altruistic?

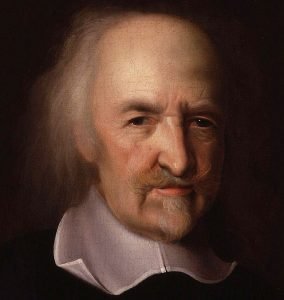

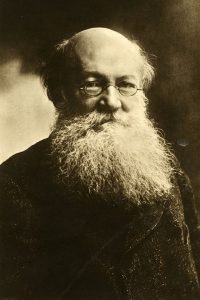

There are definitely those who would argue the latter. They take issue with the view made famous by philosopher Thomas Hobbes that the “state of nature is red in tooth and claw”, and that left to our own devices we would all gladly trample over one another to get ahead. Rather, people like the 19th century anarchist and political philosopher Peter Kropotkin or the contemporary historian and author Rutger Bregman argue, cooperation and collaboration are just as prevalent as competition (if not more so) across human societies throughout history. (And indeed, across large parts of the animal kingdom too).

Historically, economic theory struggled to deal with altruism. The classical notion of “homo economicus” was based on the idea that we are all rational individual agents, whose sole goal is to maximize our own private utility value (i.e. make our own lives better). If this is the case, then people giving things away to help others, with no expectation of a return (and quite probably resulting in a loss to themselves) makes no sense.

Economists tried to solve this problem by arguing that we do in fact get a return for apparently selfless acts of generosity in the form of a “warm glow”. Hence, presumably, we can safely go back to viewing everyone as fundamentally selfish. This workaround led the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson to note wryly that “economists shy away from altruism almost comically… caught in a shameful act of heroism they aver “Shucks, it was only enlightened self-interest…””.

Today it is clear that “warm glow theory” is at least partly right, as neuroscientific research has confirmed that giving money to charity and other pro-social acts trigger reward centres in the brain that result in us feeling better. (In much the same way as less wholesome activities like gambling, taking drugs and eating chocolate do). And if we were simply reward-seeking machines, driven simply by responding to stimuli in search of the next dopamine hit, perhaps this would be the whole story – but of course it isn’t. Most of our actions are driven by a hugely complex range of factors, ranging from unconscious biological ones to conscious social ones, and this is very much the case when it comes to giving.

So what does make us give?

Upbringing

Many of our lasting habits are formed at an early age. If you are raised in a religious context then a duty to give might well be an explicit part of your faith. But even if you aren’t, if the ethos of your family or community emphasizes the importance of being kind and giving to others, then the likelihood is that you will continue to do so when you grow up and have your own money and resources.

Life Experiences

As we go through life, we all have experiences that lead us to become aware of the work of charitable organisations. Sometime this reflects happy moments – for instance getting involved with a local conservation group after visiting a nature reserve, or seeing the impact that a literacy organisation has on our child’s love of reading. But it may also reflect much harder times in our lives – such as when we lose a loved one or suffer physical or mental illness ourselves and need to rely on the support of a charity.

For many people, the personal connection to a cause that comes from these life experiences is one of the biggest factors that gets them giving or makes them give more.

Other People

Giving is sometimes presented as a private and entirely individual matter, but in reality other people play a big part in our decisions to give.

This may simply be because they ask us. It is sometimes said that “people give to people”, and it is certainly the case that being asked remains one of the biggest motivating factors there is for donating. This is especially true if the person doing the asking is someone we already know or trust.

However, other people don’t necessarily need to ask us to give in order to get us giving. Many studies have found that we are more likely to be generous when we can see that other have already given, because we feel a sense of peer pressure. (Social media has almost certainly amplified this effect by allowing everyone to publicise their own giving and volunteering more than ever before).

We also worry about how we look in the eyes of others, so we are more likely to give in situations where we might be concerned that others will see us as ungenerous if we don’t. (Researchers have even found in experiments that this effect can be replicated simply by putting up images of “watching eyes” when asking people to make a donation).

Why do Rich People Give?

We have made it clear already that philanthropy is not just about wealthy people giving. However, there is also no denying that this is an important element of the wider picture, and there is often particular interest in what drives rich people to give away their money.

In one sense, of course, wealthy people are just like the rest of us (only with more money), so all the factors outlined above still apply. They may give as a result of religious beliefs, or because of experiences they have had in their lives, or simply because they want to feel a “warm glow”.

However, there may be additional factors that drive wealthier people to give. For instance, whilst caring what others think may play a role in giving for all of us, it is only when significant amounts are involved that wider public opinion also becomes a factor. It is a caricature to suggest that philanthropy is merely a self-interested means to bolster reputation or boost social status, but equally it is clear that such considerations do play a part in shaping some wealthy people’s willingness to give their money away.

Conversely, some wealthy people clearly see their philanthropy as a duty: part of a “social contract” that requires them to give back to the society that has allowed them to be successful, or to particular organisations or communities that have helped them on the way.

An increasing number of wealthy people are also uneasy about the scale of inequality in the world today, and see their giving as an important and necessary element of wider efforts to redistribute resources more equitably.

Another factor that drives rich people to give is concern about the alternatives. There is a common fear for instance (particularly among those who have not come from wealth themselves), that if they leave too much money to their offspring it will ruin them. This has historically been a strong motivation for giving the money away instead.

Sir Francis Bacon warned of the dangers of leaving too much money to one’s offspring all the way back in 1625, counselling that:

“A great state left to an heir is as a lure to all the birds of prey round about to seize on him, if he be not the better ‘stablished in years and judgment”

And one of the most famous philanthropists of all, Andrew Carnegie, was vehemently opposed to inherited wealth, arguing that:

“The parent who leaves their son enormous wealth generally deadens his talents and energies and tempts him to lead a less useful and less worthy life than he otherwise would.”

Does motivation matter?

It should be clear by now that there are many different reasons why we all give; whether you are a billionaire philanthropist or an everyday donor.

In one sense it is important to understand these motivating factors, so that we can find ways of encouraging people to give more to help address the many pressing issues facing the world today. But in another sense, does it really matter why we give? If someone is supporting a good cause, but doing it for reasons that we don’t think are the “right ones”, does that lessen the value of their gift? Or do we just need to accept that people might give to charity for all kinds of reasons, and that to an extent the end justifies the means?