As we enter LGBT+ history month, we shine a light on one piece of the puzzle that often gets overlooked: the role that philanthropy and charity has played.

4th February 2022

It is once again LGBT+ History month. This will no doubt bring to light many fascinating facts and stories from the long struggle to ensure equal rights and freedoms for the LGBT+ community, and perhaps has even greater relevance this year in the wake of the recent announcement that a new national LGBTQ history museum for the UK will open this spring. However,one piece of the puzzle that often gets overlooked is the important role that philanthropy and charity has played.

This is perhaps in part because the history of philanthropy is itself a subject that deserves far more study that it currently gets. Equally, it may be because the relationship between rights-based campaigns and philanthropy is often complex and brings to light many issues — both positive and negative. However, given that social movements are playing an ever more prominent part in civil society — and the potential tensions between our notions of charity and those of justice continue to cause widespread debate – it seems more important than ever that we understand the history of the fight for LGBT+ rights and what we can potentially learn from it about the role philanthropy can play in driving social change. (NB: for a great overview of the broad history og LGBT+ rights in the UK, I definitely recommend this British Library blog).

One of the major strengths of philanthropic funding is that by its nature it can take greater risks when it comes to supporting unpopular causes (as it is not accountable to voters or shareholders), so it has often played an instrumental role in funding rights-based campaigns in their very early stages and thus ensuring that issues can eventually be brought from the margins into the mainstream. This makes philanthropy (at its best) a crucial part of a democracy, as it can help to overcome the “tyranny of the majority” that can result through the ballot box; where minority groups struggle to have their voices heard because they never have sufficient numbers to exert influence through voting.

An additional benefit that philanthropy can often bring, apart from just the money, is legitimacy for a cause. In the early days of LGBT +philanthropy in the US in the 1970s, the field relied on a handful of foundations that were themselves from within the gay and lesbian communities, such as the Astraea Foundation and the Horizons Foundation (originally the Golden Gate Business Association Foundation, founded in 1980 by a group of gay local business owners, due to dissatisfaction with their local United Way’s failure to distribute enough to LGBT causes in an area with a sizeable gay community). The emergence of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, however, led to well-known mainstream funders such as the Geffen Foundation, Ben & Jerry’s and Levis getting involved. Although some of these funders stuck to funding treatment for AIDS as a medical condition, others broadened out into supporting broader calls for gay rights too; bringing a new level of mainstream legitimacy to the cause. (For more on the US history of philanthropy and LGBT+ history, check out this great report on “Forty Years of LGBT+ Philanthropy: 1970–2010” from LGBT Funders).

One challenge the history of LGBT+ rights and philanthropy demonstrates very clearly is the tension between idealism and pragmatism that is so often a struggle for social movements. Philanthropic funders and charitable organisations have, by their nature, usually erred towards gradual change and the need to work within existing systems. But this has often brought them into conflict with those who favour more radical action and believe in the need to reform society more fundamentally.

The focus of the movement in the UK in the first half of the 20th century was to secure the decriminalisation of homosexuality so that gay and lesbian people were not forced to live secretly, in constant fear of arrest. Following the publication of the Wolfenden Report in 1957, which recommended the decriminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults, the Homosexual Law Reform Society (HLSR) was established, along with a linked charity (The Albany Foundation). These were instrumental in ensuring the implementation of the Wolfenden Report recommendations, but many critics came to feel that they were too close to the existing establishment and therefore complicit in watering down many of the more radical proposals. Some even branded founder Anthony Grey an “Uncle Tom”.

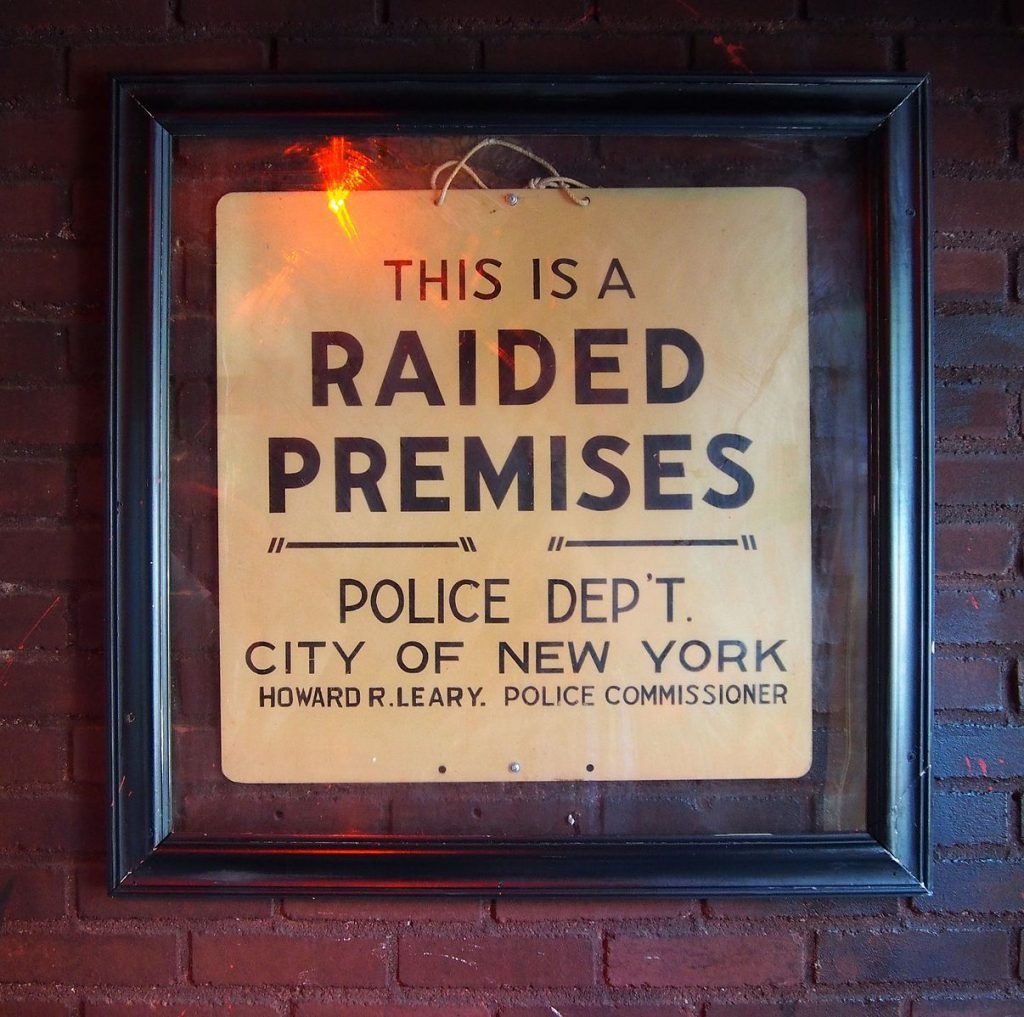

Following on from the Stonewall uprising in New York in 1969, the LGBT+ rights movement in the UK took a more militant turn as those who demanded radical action came to the fore. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) formed in the US in 1969 and a UK chapter was then set up in 1970, centred on the London School of Economics. The GLF only existed for about 4 years before internal divisions saw it splinter, but in that time it engaged in a series of high-profile direct action protests and also organised the UK’s first ever Pride march (in London in 1972). Its approach and many of its tactics set a template for other radical LGBT groups that followed it in the 1980s and 1990s, such as Outrage!- whose co-founder Peter Tatchell became a prominent figure, but whose adoption of ‘forced outings’ of homosexual public figures proved highly controversial.

The tension between moderates and radicals, as in so many movements, swung back and forth over time as new rights opened up for the LGBT+ community and new challenges also emerged. The introduction of “Section 28” legislation by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher in 1988 — which banned local authorities from “promoting homosexuality” or “promoting the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”- galvanised the LGBT+ rights movement in the 1990s in opposition to what was seen as highly regressive attempt to demonise homosexuality once more.This led to the creation of new organisations, such as the charity Stonewall, which has been an important voice in the ongoing fight for LGBT rights ever since. Section 28 was repealed in 2003, and there were other wins too: such as Age of Consent equality (introduced in 2001 in England, Wales and Scotland, and 2009 in Northern Ireland), and — most notably — the legalisation of first same-sex civil partnerships in 2004 and then same-sex marriages in 2013.

The other big challenge that history highlights is that of “hyperpluralism”. This is where a right-based movement can over time splinter into many sub-movements, each with their own priorities and approach that may be incompatible, and as result it is hard to maintain the coherence of the movement as a whole. Philanthropy can potentially exacerbate this problem, since by its nature it tends to promote plurality because it reflects the differing priorities and choices of a wide range of different donors.

The political scientist Kristin Goss, in her study of philanthropic funding for feminist movements in the latter half of the 20th century, poses the key question thus:

Does philanthropy encourage a robust group-based politics, or quash it? Have foundations contributed to the fragmentation of U.S. society by encouraging identity politics, or have foundations contributed to the unification of the United States by bringing previously marginalized groups into social, political and economic life?

Hyper-pluralism may present a similar challenge for the LGBTQ+ rights movement today, as debates about intersectionality and the differing (and sometimes contradictory) priorities of different subgroups within the movement continue to give rise to strong feelings and disagreements. These are often extremely complex issues, but the lesson from history is that when pluralism within a movement turns into division, that can significantly undermine the force of the movement overall.

Hyper-pluralism may become even more of a challenge in the future if efforts to drive social change increasingly adopt ‘leaderless’ or decentralised models,, because there is little or no ability to dictate focus or strategic direction. As Jo Freeman argued in her seminal 1972 essay “The Tyranny of Structurelessness”:

The more unstructured a movement is, the less control it has over the directions in which it develops and the political actions in which it engages. This does not mean that its ideas do not spread… But diffusion of ideas does not mean they are implemented; it only means they are talked about. Insofar as they can be applied individually they may be acted on; insofar as they require coordinated political power to be implemented, they will not be.

(For more on Freeman’s paper and its relevance to modern social movements, see this blog I did for HistPhil).

A further challenge may then be that those who wish to undermine the ability of civil society to speak truth to power are able to exploit this tendency toward hyper-pluralism. The phenomenon of “astroturfing” has already seen many examples of new organisations and online networks emerging which look like expression of grassroots activism, but are in fact controlled by state or corporate interests. The aim of these astroturfing entities is often to create artificial hyper-plurality, giving the false impression that views on an issue are divergent and thereby stifling the efforts of genuine civil society groups to advocate or campaign. (For more on the challenges to civil society authenticity in the digital age, here’s a piece I did for Stanford’s Digital Civil Society Lab blog)

As technology opens up new ways to organise, so that movements like Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter have come to the forefront, the story of efforts to drive social change over the coming years is likely to be increasingly one of traditional funders and charities having to work with or support looser, network-based movements. As such, understanding the historical context of the relationship between philanthropy and movements in areas such as LGBT+ rights is going to be vital, and could give us invaluable insights into the opportunities and challenges the future may bring.