We explore the idea that “in an ideal world there would be no philanthropy”: why does it have such deep roots, how should we understand it, and is it right?

14th July 2023

The other day I was involved in a conversation in Liverpool with someone who wasn’t by any means a philanthropy expert, and they said something that stopped me in my tracks: that in their view “in an ideal world we wouldn’t need charity, because the government would take care of everyone”. Now this definitely wasn’t the first time I have heard this idea (tbh it takes quite a lot these days for me to hear a genuinely new idea about philanthropy – because I’m old and haggard), but what really struck me is how much enduring power it (or versions of it) have had. The philosopher Bertrand Russell, for instance, wrote in a 1932 essay that “in a just world, there would be no need for charity”, and even at that point the thought wasn’t especially new: as far back as the 18th century, we can find pioneering women’s rights campaigner and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft arguing that “it is justice, not charity that is wanting in the world”. So the roots of this idea run very deep through the historical lineage of philanthropy. And this got me thinking: why does it exert such a powerful grip? What is it about this idea that makes it occurs equally to famed philosophers grappling with deep questions about the nature of charity 200 years ago, and to normal members of the public today who are stopping to think about philanthropy for the first time? And, more importantly, is it even right?

To answer these questions we need to unpick what we actually mean by “philanthropy”; we need to explore what role it plays in our society and how it relates to our notions of justice and equality; and we need to consider what it would actually mean to live in a world where philanthropy didn’t exist. And that’s what I am going to aim to do in this article (without getting too carried away, of course, as these are pretty big topics!)

It is worth saying at this point that one obvious response to any argument about philanthropy not existing in an ideal world is to point out that we don’t live in an ideal world and that in reality philanthropy does exist in society at present. Hence, even if we think the desirable end goal is to do away with the need for philanthropy, it makes more sense to engage with the world as it is (not just as we would like it to be) and focus our efforts on reforming philanthropy in whatever ways we deem necessary, rather than getting lost in theoretical arguments about whether its existence is a good thing or not. There is certainly something to be said for this line of thinking, particularly for anyone who is inclined to any extent towards pragmatism. However, for the purposes of this article I’m going to put this kind of argument aside and take the thought experiment seriously: I’m going to assume from the outset that it is actually possible to reach utopia, as the question I want to explore is whether it is right to suppose that in this scenario philanthropy would cease to exist. And whether we should see that as a good thing or not.

What is the argument?

First of all, let’s look briefly at what the argument actually says. To do so, let’s put it in its broadest form: “In an ideal world, there would be no philanthropy”. We can then start to unpick this – it is clear, for instance, that the premise (“if the world was ideal”) immediately raises other questions: what would it mean for the world to be “ideal”? Does everyone agree on this? What is it about the ways in which the world is currently non-ideal that give rise to philanthropy? We might also question whether the conclusion “then there would be no philanthropy” is somewhat ambiguous as stated: is it saying that there would be no possibility of philanthropy, or is it saying that there would be no need for philanthropy? We shall see that these two ideas are often blurred (and there is a lot of natural overlap between them), but that it may be useful to distinguish between them because they imply different reasons for supposing that philanthropy might cease to exist in the ideal world we are being asked to imagine.

What do we mean by “philanthropy”?

The other thing we should do is ask what we mean by “philanthropy” in this argument. This is a notoriously difficult question to answer (in fact, the challenge of providing an exact definition of “philanthropy” and the possible means of circumventing it form the entire basis of my recent book What is Philanthropy For? so I am well aware of the difficulties!) However, even if we can’t provide an exact definition there are a few points of clarification we do need to make.

For one thing, is “philanthropy” being used in such a way as to imply financial giving by the wealthy? This is certainly a fairly natural usage these days – indeed part of the Oxford English Dictionary definition of “philanthropy” is “practical benevolence, now esp. as expressed by the generous donation of money to good causes”. However, we also need to be aware that there are many people who would take issue with the idea that philanthropy necessarily implies wealth, and would like to reclaim its core meaning of “love of humanity” so that it is something that can be used to describe acts of generosity and kindness at all levels (and involving more than just money). This is particularly important in the context of the arguments we are currently exploring, as one interpretation of what it would mean for the world to be “ideal” is that we no longer have the huge inequality and disparities of wealth that exist in the world today. The implication would then be that philanthropy is no longer possible (on the assumption that inequality is a precondition of philanthropy) and potentially also no longer necessary (on the twin assumptions that we have addressed inequality to the extent that there is no longer any poverty, and that dealing with poverty is the sole focus of philanthropy).

We shall return to the question of inequality and its relationship to philanthropy shortly, but for now we just need to note that if we take a more expansive view of philanthropy as encompassing not only the donations of the wealthy, but also everyday giving by people of average wealth, then it is no longer clear that the conclusion of our main argument follows from the premise. Assuming that an ideal world is one in which society is far more equal, but still allowing that some might have more than others, there would still be plenty of room for philanthropy, understood in this broader sense, to exist (albeit perhaps less of it and of a different character than we have now). One might, of course, suppose that there was no longer any need for philanthropy in a more equal society (so that even if it could theoretically exist, it wouldn’t), but this presupposes that philanthropy only exists as a reaction to poverty (which is something I will come back to shortly).

One might also suppose that in our ideal world we have reached such a level of equality that there is literally no possibility of there being “haves” and “have nots”, and thus philanthropy is rendered impossible even in a modest sense. However, this assumes that philanthropy must be fundamentally asymmetrical; in reality there have been throughout history – and continue to be today – many counter-examples. The historian Frank Prochaska, for instance has written of the rich traditions of “giving by the poor to the poor” that have often been left out of accounts of the Victorian golden age of philanthropy in favour of the stories of individual wealthy donors and their great deeds, but which were a major component of the culture of philanthropy of the time. Likewise in many places around the world there are traditions of “horizontal philanthropy” that involved people in similar life circumstances giving to support one another based on bonds of solidarity and mutual aid, rather than any sense of transferring from haves to have nots. Even in entirely equal societies, it is reasonable to argue that these forms of giving would persist. (One might, of course, take issue with the idea that we are still talking about “philanthropy” in this scenario, but if we have got down to arguing about semantics then at least the actual nature of the debate is clearer).

The other point to be aware of in terms of how we are using “philanthropy” is that historically a common tactic has been to draw a distinction between this and the idea of “charity”. Charity, it is claimed, addresses symptoms at an individual level and is driven by pity and emotion, whereas philanthropy seeks to address underlying causes at a more systemic level, and to do so in a more rational and effective way. This is important for our current purposes because in drawing this distinction it is sometimes claimed that the fundamental aim of philanthropy is to make charity redundant. The historian Robert Gross writes, for instance, that

“By eliminating the problems of society that beset particular persons, philanthropy aims to usher in a world where charity is uncommon – and perhaps unnecessary.”

Similarly the former President of the Carnegie Corporation, Vartan Gregorian, declared in a 2009 speech that:

“philanthropy works to do away with the causes that necessitate charity.”

There are clear similarities here with the argument we have been considering: the ideal world being posited is obviously somewhat different (presumably it is not one in which inequality has ceased to exist, for instance), but the suggestion is still that by remedying existing flaws in our society we can do away with the need for a certain kind of generosity. In this case, of course, philanthropy itself is presented as the solution, and charity as part of the problem. This suggests that when considering our main argument about whether philanthropy would exist in an ideal world, it is worth bearing in mind the distinction between philanthropy and charity, as the arguments may not apply equally to both (or may apply in different ways).

What would it mean for the world to be “ideal”?

Let’s look now at the “ideal world” bit of the argument we are considering. In some statements of the argument we are pretty much left to fill in for ourselves what it would mean for the world to be ideal, but in other versions further detail is added that gives a much clearer sense of what is meant hinted at. From those we can infer three key attributes of this ideal world:

- There is little or no injustice.

- There is little or no inequality.

- The government meets people’s welfare needs.

I should reiterate here that the purpose of this article is not to ask whether it is likely or possible that these conditions could be met (that is for a whole different philosophy seminar…); what we are concerned with is whether each of these criteria actually implies that philanthropy would no longer exist, and whether that should be seen as a good thing or not.

In a just & equitable world would there be no philanthropy?

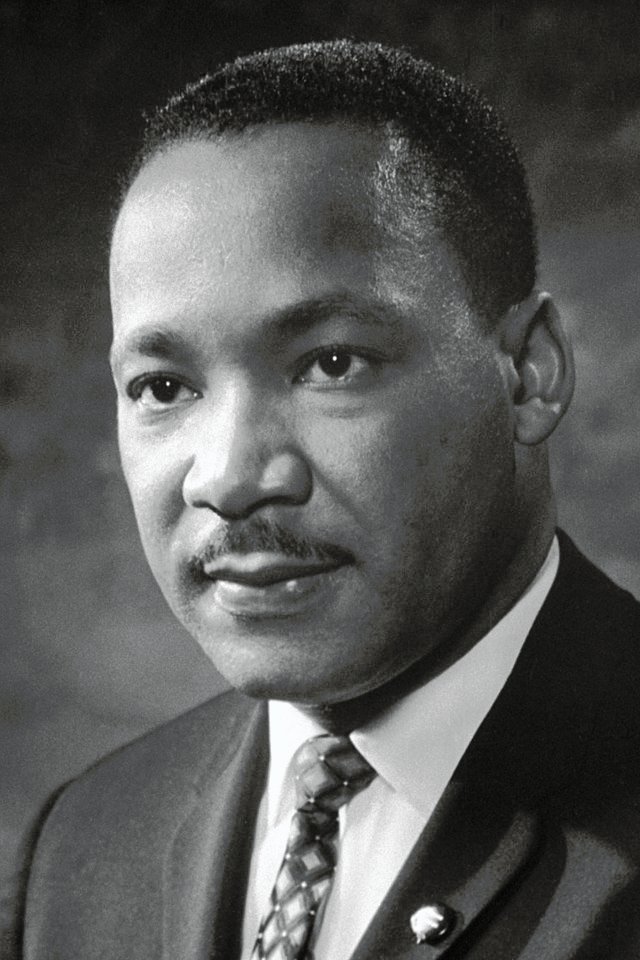

Let’s take injustice and inequality together in order to understand how they relate to philanthropy – partly because I’m trying to keep this article at a manageable length, but also since inequality can, in one sense, be understood as a form of economic injustice, as demonstrated by Dr Martin Luther King’s famous remark that:

“Philanthropy is commendable, but it must not cause the philanthropist to overlook the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary.”

In order to think that a truly just and equitable world would contain no philanthropy, presumably we have to believe either that injustice and inequality are necessary preconditions of philanthropy (so without them, philanthropy is simply not able to exist); or that addressing injustice and inequality is the only meaningful purpose for philanthropy (so without them philanthropy could exist but there is no need for it to). But is either of these obviously true?

Let’s take the latter first (i.e. the idea that addressing injustice and inequality is the sole focus of philanthropy). It seems pretty clear in one sense that this isn’t true, as there are plenty of examples of philanthropic giving that you would struggle to frame in terms of them being a direct response to perceived injustice or inequality: what about giving to art galleries and museums, or to a local community garden, or to scientific research institutions? Some critics would argue, however, that these sorts of examples show precisely what is wrong with philanthropy in its current form: that allowing donors to have free choice over what they give to means that resources are distributed according to the dictates of personal preference rather than according to the requirements of justice. The political philosopher Chiara Cordelli argues, for instance, that:

“Philanthropy should be understood foremost as a duty of reparative justice… Affluent donors should, as a matter of moral duty, exercise no personal discretion when deciding how to give and to whom. Indeed, they should regard their donations as a way of returning to others what is rightfully theirs.”

It is fairly apparent from the liberal use of “should” in this statement that this is a normative view rather than a descriptive one (i.e. a view about how the world would ideally be, rather than how it currently is). But for those who agree with Cordelli on this normative point, it is presumably true that in their ideal world there would be no philanthropy – since we are being asked to accept that the only acceptable function of philanthropy is to act as a means of delivering justice, and if there is no injustice ergo there is no need for philanthropy. For those who stop short of embracing this view, however, it is less clear that a just world would necessarily entail no philanthropy – if we accept that some of the forms of giving that are not justice-based do count as “philanthropy”, then surely at least these would continue to be relevant in our ideally just world?

Let’s turn now to the other presumption – that injustice or inequality are necessary preconditions for philanthropy. It is worth saying at this point that we need to be slightly careful about conflating these two things: although many these days would accept that an unequal world must obviously be unjust, not everyone would agree by any means, and if we go back in history this certainly wasn’t the case. The medieval view of poverty was that it reflected a natural order imposed by God: some people were rich, others were poor – so there was definitely inequality, but this couldn’t be seen as an injustice since it reflected God’s will. Hence, as the historian Suzanne Roberts notes:

“Medieval charity never intended to eliminate or solve social problems. Medieval people had no social theory of poverty, and they did not expect to change the social order; following Saint Paul, they believed that the poor would always be among them”.

It was only with the advent of the Enlightenment, and the changes this brought in ideas about the nature of property, that people began to see poverty as something which reflected a fundamental injustice in the way society was structured. As Immanuel Kant put it in his Lectures on Ethics:

“Although we may be entirely within our rights, according to the laws of the land and the rules of our social structure, we may nevertheless be participating in a general injustice, and in giving to an unfortunate man we do not give him a gratuity but only help to return to him that of which the general injustice of our system has deprived him.”

(NB: for more on how thinking about the nature of poverty has evolved, and what this has meant for philanthropy, see this WPM article: https://whyphilanthropymatters.com/article/cold-as-charity/)

If we accept that philanthropy is, to some extent, a reflection of injustice and inequality, that still leaves open the question of what conclusion we should draw from this. Does it mean that we need to abandon philanthropy and look elsewhere, or can philanthropy be seen a tool to address inequality and injustice? One of the most influential voices on this question has been Andrew Carnegie, whose essay Gospel of Wealth has had a profound impact on shaping thinking and practice about philanthropy since the late 19th century. In this essay, Carnegie acknowledges that capitalism results in inequality, but argues that this is an unfortunate inevitability and that the best method of dealing with it is to ensure that wealthy people recognise their responsibility to give back to society through suitably strategic philanthropy:

“There remains only one mode of using great fortunes; but in this we have the true antidote for the temporary unequal distribution of wealth, the reconciliation of the rich and the poor… It is founded upon the present most intense Individualism and the race is prepared to put it into practice by degrees whenever it pleases. Under its sway we shall have an ideal State, in which the surplus wealth of the few will become, in the best sense, the property of the many, because administered for the common good; and this wealth, passing through the hands of the few, can be made a much more potent force for the elevation of our race than if distributed in small sums to the people themselves.”

This line of thinking has provided a basis for many subsequent defences of philanthropy, including bullish examples such as the philanthrocapitalism movement of the early 21st century, which followed Carnegie in arguing that giving by the wealthy is actually preferable to any alternative method of redistribution. Others, meanwhile, have embraced Carnegie’s basic idea in a more tempered way; arguing that philanthropy can play a role in addressing injustice and inequality, but that this role is partial (alongside taxation and government spending) and that it also requires us to make a conscious effort to recalibrate our approaches to giving with the aims of justice and equality in mind. (This is essentially the thesis of Ford Foundation President Darren Walkers book “From Generosity to Justice: A New Gospel of Wealth” which – as the title suggests – tries to tie together Carnegie’s view of philanthropy with the justice-oriented views of Martin Luther King and others).

Not everyone, however, is on board with the idea that philanthropy can address the fundamental concerns about its own relationship with inequality and injustice. From the Enlightenment onwards, many have argued that we must look elsewhere if we are to redistribute resources in a just way- and this usually means through taxation. The key point here is that even if philanthropy tries to focus more on justice and equality, it is fundamentally different in nature to taxation in ways that make it incapable of doing so. Taxation is a duty – an obligation that we all have to fulfil. The money raised through it is distributed according to decisions made by democratically elected bodies, and people’s needs are then met as a matter of rights. Philanthropy, conversely, is a choice – something we take it upon ourselves to do voluntarily. The decisions about where to give are made by unelected individuals or organisations, and when people’s needs are met it is done as a matter of benevolence (not a matter of rights). As the political philosopher William Godwin (aka Mr Mary Wollstonecraft) put it in his 1793 work “An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice”:

“The effect produced by this accommodating doctrine is to place the supply of our wants in the disposal of a few, enabling them to make a show of generosity with what is not truly their own, and to purchase the submission of the poor by the payment of a debt. Theirs is a system of clemency and charity, instead of a system of justice. It fills the rich with unreasonable pride, by the spurious denominations with which it decorates their acts; and the poor with servility, by leading them to regard the slender comforts they obtain, not as their incontrovertible due, but as the good pleasure and grace of their opulent neighbours.”

Similar sentiments can be found today in articles like one the Guardian commentator Owen Jones wrote in 2018, which declared that: “We don’t want billionaires’ charity. We want them to pay their taxes”, or in historian Rutger Bregman’s viral appearance at the 2019 World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, where he called on the world’s global elites to “stop talking about philanthropy and start talking about taxes”.

Arguments like these suggest a rather binary view of the relationship between taxation and philanthropy; in which we simply need to raise taxation to a sufficient level to meet the demands of justice and that will then then mean the disappearance of philanthropy. Again, this might either be because we have done away with the need for philanthropy by meeting all of society’s needs through taxation (which would presumably be OK); or it might be because we have made it impossible for anyone to have the disposable wealth that would allow for philanthropy (which would presumably not be a good thing if there were still needs in society that would benefit from philanthropic attention).

But is this really how tax and philanthropy fit together? Justice may well demand that the wealthy pay more in tax (I would certainly buy that idea, as would the many wealthy people involved in movements like Patriotic Millionaires), but are we to believe that this duty is absolute, so that by paying taxes these people would have fulfilled their whole duty to society and may not have any additional resources left over with which to do philanthropy? This seems unfeasible to me. Even with the introduction of significant wealth taxes, the very rich would still have large sums available to them to give away so they could engage in philanthropy (and, I would argue, they should). If they chose to do so, having paid all their taxes, would we view this giving as being above and beyond duty (the fancy philosophical term for this is “supererogatory”)? If so, then at this point would be OK for these philanthropists to choose where to give based on their own interests and preferences (which may be guided by notions of justice and equality, but need not necessarily be)?

Coming back to our original thought experiment, we can thus imagine a world in which we all pay far more in tax – which would meet the demands of justice and would presumably result in less inequality (although perhaps not none) – but people are still free to engage in supererogatory philanthropy with any additional resources they have left. Of course, some might argue that this isn’t an ideal world at all if there is still potential inequality and people have private wealth, but that is taking a fairly extreme view of things! Unless we are hypothesising a scenario in which all personal property has ceased to be, then presumably people still have assets of various kinds, and if taxation is not absolute then some of those are disposable; so we would still have the required resources for philanthropy (albeit this might be at a vastly reduced level , and it might have far more in common with models of horizontal giving and mutual aid than the current approaches we rely on).

State and Philanthropy

Let us turn briefly now to the third criterion we identified earlier for what might count as an ideal world: that all needs are met by the government. Obviously, the arguments we have just considered about taxation and justice are highly relevant here, as they provide the most obvious basis for thinking that state provision of welfare is a preferable alternative to philanthropic provision (because it is based in duties and rights, and it has democratic legitimacy). But I want to consider two related questions: does it actually make sense to suggest that government could or should replace all philanthropic provision? And are there arguments in favour of philanthropic provision even where state provision is possible?

To answer the first, it pays to take a historical perspective and look at how philanthropy and state provision have actually interacted over time. In the UK, the story is broadly one in which philanthropy led the way in most areas for a long time – both in highlighting needs and in addressing them – before the state eventually (and often reluctantly) started to accept responsibility for meeting the welfare needs of citizens in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The birth of the Welfare State in 1948 obviously then shifted the balance much more towards the state. Some believed that this would signal the death knell for philanthropy, but of course it didn’t, and there was still plenty of room for philanthropy to focus on things the state wasn’t doing (and also to fill in gaps in state provision, or to campaign and advocate in the face of state failure). In other places that have sizeable welfare states, such as Scandinavian countries, we see a similar story: philanthropy may have moved out of certain areas (or may never have moved into them in the first place if the government was the early mover in providing services), but it has certainly not disappeared altogether. (The only places in which philanthropy might genuinely be said to have disappeared altogether are all-encompassing communist states like the former USSR, but this also reflects active efforts on the part of the government to stifle or appropriate civil society, so it is hard to say that the diminution of philanthropy was a direct consequence of the government successfully meeting everyone’s welfare needs).

When it comes to the respective roles of philanthropy and state, it helps to think in terms of a Venn diagram: there are some things that we look to the state to provide, others that we see as the preserve of philanthropy, and then an overlap in which there are things that can be provided by either or by both. The exact contours of this Venn diagram are contested, and shift over time as our expectations of state and philanthropic provision evolve. Right now, in the “state responsibility” space we might put things like rubbish collection and policing; whilst in the ”philanthropic provision” space we might put The Scouts and the Girl Guides, or model railway societies (to use my favourite example again). In the intersection of the two we would find things like the lifeboat service (which is run through voluntary provision in the UK, but by the state in the US), or public libraries (which have their roots in philanthropy and have passed into state ownership in many cases, but in some cases are now being handed back).

To say that in our ideal world philanthropy would not exist is therefore to say that this Venn diagram should become a circle, in which the space of state provision swallows all else. In practice this means we are suggesting that the Girl Guides, the Scouts and the local model railway society should all be state-run; and surely only the most die-hard Leninist would accept that conclusion? Obviously, I have chosen edge cases here, where the idea of state control seem particularly ridiculous (because I love a cheap, showy rhetorical trick), but even in less absurd cases, there may be valid arguments in favour of philanthropic provision even if it is theoretically possible to replace it with state provision. For one thing, altruism, generosity and gift giving are pretty fundamental parts of all human societies (and indeed, many animal ones), which create important connections of compassion, kinship and reciprocity, so could we realistically expect them ever to be entirely replaced? And if we can’t, does it not make more sense to nurture those impulses and get the benefit of them, rather than trying to stifle them? There is also the argument, first made famous by Alexis de Tocqueville, that voluntary activity has value as a “nursery of democracy”, because it teaches people vital skills of collaboration and civic engagement. This has led some to argue that there is additional value in looking to provide welfare services through voluntary means- the social scientist Constance Braithwaite argued in her 1938 book The Voluntary Citizen, for instance, that:

“The qualities of citizenship desirable in the democratic community of the future are far more likely to be developed by active participation in the work of voluntary associations than by methods of mass propaganda and deification of the State.”

One can also argue that state provision is more likely to reflect the majority opinions of the day, and as a result may run greater risks of leaving out marginalised groups or failing to adapt to changing needs. Indeed, one of the leading architects of the UK welfare state, William Beveridge, argued in his 1948 book Voluntary Action that “the democracy can and should learn to do what used to be done for public good by the wealthy’, but cautioned that ‘the problem is that of getting the democracy to give for new things, and unfamiliar needs.” As a result:

“Voluntary Action is needed to do things which the state should not do, in the giving of advice, or in organising the use of leisure. Itis needed to do things which the state is most unlikely to do. It is needed to pioneer ahead of the state and make experiments. It is needed to get services rendered which cannot be got by paying for them.”

Perhaps, then, we need to be careful about assuming that in our ideal world we should allow state provision to do away with philanthropy, even if it is possible to do so.

Conclusion

The idea that “in an ideal world there would be no room for philanthropy” clearly taps into important questions about the nature of philanthropy, its relationship to government and how we are to view it relation to concerns about inequality and injustice. But it is hard to conclude that the argument’s premises justify its conclusions in their strong form. A future in which society is more equitable and just, and the government has a greater role in looking after citizens, is almost certainly one in which there would be less excess wealth available for philanthropy and also less need for it as a means to address problems. However, that doesn’t mean there would be none of either. Yes, there might be less philanthropy, and yes, it might look markedly different from a lot of the philanthropy we have today, but it would still be there. And for my money that’s probably a good thing, since there is value to philanthropy that cannot be replaced by the state or the market.

As a parting thought it is worth noting that this whole thought experiment might actually be less theoretical than it seems at first glance. In the context of concerns about the impact of automation, and the shift to a “post-work” future as we are all replaced by robots and AI systems, one of the policy solutions often discussed is the idea of some form of universal basic income (UBI). In its full-fat version, at least, UBI doesn’t look that dissimilar from the “ideal world” scenario we have been exploring, so perhaps now is a good time to be thinking through these questions….