As debate grows over whether we should be more concerned about over-population or declining birth rates, we explore why philanthropy has such a problematic history when it comes to engaging with population issues, and what lessons this holds for modern-day donors and non-profits.

19th January 2023

Are there too many people on our planet, or too few? This is a contentious question, and many may feel as though it cannot (or perhaps should not) be answered one way or the other. However, debates over population issues have been growing in intensity in recent years, and look set to become a major focus of mainstream debate in 2023 and beyond, so it is increasingly hard to ignore them.

These are also debates that may have particularly significant implications for philanthropy and civil society. To understand why, it is necessary to look back at why ideas about giving have historically long been entwined with ideas about population; to consider why philanthropic donors, funders and non-profit organisations continue to be important voices in current population debates; and to understand why this might raise challenging questions about the role and influence of philanthropy in our society.

What is the Debate?

First it is worth delving a little bit deeper into the exact nature of the debates about population to get a better sense of the views on different sides and where they come from.

Until recently, the consensus (insofar as there was one) was probably that overpopulation is the main issue, with many having concerns about the environmental and societal impact of a rapidly growing population stretching Earth’s resources beyond breaking point. This is a view whose historic roots can be traced back at least as far as the work of the clergyman and population theorist Thomas Malthus in the 17th century, in his Essay on the Theory of Population.

Malthus famously argued that the unchecked growth of human populations would inevitably lead to collapse, as people over-competed and thereby depleted scarce resources. (He also had some pretty problematic opinions about charity as a result of these views, as we shall see in a moment…) Malthus’s views were initially highly influential, but over time they became somewhat discredited as it became apparent that such collapses did not happen in practice, and that as populations around the world grew they were able to generate sufficient resources to meet their needs and thereby remain broadly stable.

In the second half of the 20th century, however, Malthusian ideas were picked up again by some in the growing environmental movement, although now in the guise of concerns about the impact of rapidly growing human populations on our planet (rather than worries about risks to the established social order and the wellbeing of the middle and upper classes, which were more the focus of Malthus and his original followers). These Neo-Malthusian ideas were famously epitomised by the Stanford academics Paul and Ann Ehrlich in their 1968 book The Population Bomb, which set out a starkly doom-laden vision of imminent environmental and societal collapse within the following decades.

The Ehrlichs’ more alarmist predictions did not come to pass, but many environmentalists and conservationists (including well-known figures like Sir David Attenborough and Chris Packham) have continued to argue that overpopulation presents a major threat; even if the timescales may not be quite as imminent as previously argued. However, more recently, as rates of population growth appear to have slowed down, a new counter-movement has arisen around the idea that the biggest threat is not in fact overpopulation, but rather declining birth rates and the risk that in the future there will be too few people.

The solutions favoured by the two sides in this debate are unsurprisingly quite different. For those who are concerned about overpopulation, the focus has been on challenging economic theories based on the idea of constant growth and on seeking ways to limit future population growth through education and the promotion of family planning. (There is, of course, also the option of actively reducing current populations – but given that this immediately takes us into the territory of the Marvel supervillain Thanos and his purportedly altruistic plan to kill off half of the population of the universe in order to reduce over-consumption and thereby enhance the wellbeing of the remaining 50%, I’m going to assume this is an avenue most people will shy away from). For those who are more concerned about declining birth rates, however, the focus is on pushing pronatalist ideas and policies that encourage or incentivise people to have more children.

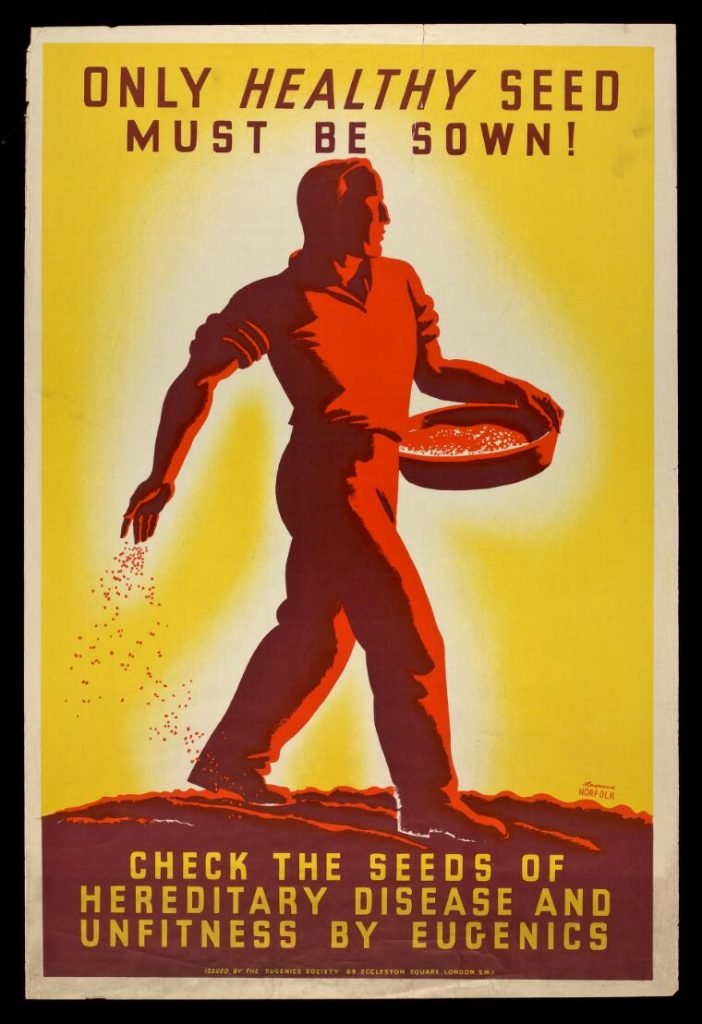

There is, of course, an elephant in the room here. We have been speaking so far as if the disagreement is a simple one between those who believe in some objective sense that there are either too many people in the world or too few; and that we therefore need either to increase or to decrease the population as a whole. However, throughout history it has been more common for people to argue that the problem is that there are not enough of the “right” people (or, conversely, too many of the “wrong” people). And this is where the spectre of eugenics rears its ugly head. As soon as you start thinking about population issues in terms of promoting or restricting the growth of particular groups in society (based on nationality, perceived racial characteristics, or views about desirable traits), you get into very murky territory that brings with it a whole host of abhorrent historical baggage. (Although people within current population debates often seem remarkably unaware of this; and are therefore sometimes willing to put forward ideas and views that have very problematic lineages).

Eugenic thinking can be reflected in ‘positive’ approaches which aim to increase the populations of ‘desirable’ groups through activities such as targeted pronatalism, or in ‘negative’ approaches which seek to limit the populations of ‘undesirable’ groups through activities such as family planning or sterilisation programmes. Philanthropy has historically experimented with all of these kinds of activities, and there are examples of philanthropy continuing to support some of them even now. Today this is rarely on the basis of an explicit commitment to eugenic beliefs, but you often don’t have to scratch the surface too hard to find views and beliefs that sound remarkably eugenics-y. (And if we’re looking back historically to the early 20th century, when eugenic ideas were much more widely accepted in society, then there are plenty of examples of philanthropists and funders just out-and-out positioning themselves as eugenicists, as we shall see in a moment).

The History of Philanthropy, Population Theory & Eugenics

Let’s turn now to consider what part philanthropy has played in the history of debate about population issues. But before we do that, we need to understand another notion that has long been at the heart of philanthropy: namely the idea that we need to discern “deserving” from “undeserving” recipients. This idea has been so influential that it has sometimes been seen as partly definitional of the very idea of “philanthropy” (particularly in contrast to “charity”). Charity, it was often argued by critics, is indiscriminate: with resources given out unquestioningly to all and guided only by emotion or religious duty. Philanthropy, on the other hand, is a matter of the head: resources are distributed in a rational way that accords with some theory about how best to achieve a desired end, so that “deserving” recipients can be supported whilst avoiding giving to “undeserving” ones at all costs.

Indiscriminate giving has been a bogeyman haunting philanthropy for hundreds of years. Andrew Carnegie claimed in 1906 (in rather eugenics-esque language, it is worth noting…) that “one of the serious obstacles to the improvement of our race is indiscriminate charity”, and that “of every thousand dollars spent in so-called charity today … it is probable that $950 is unwisely spent; so spent, indeed as to produce the very evils which it proposes to mitigate or cure.” This idea that that indiscriminate giving was not merely wasteful but actively problematic because it bred dependency and encouraged laziness on the part of the poor was a common refrain. Over a century before Carnegie, the writer Dr Samuel Johnson argued that “you do more good to [the poor] by spending [money] in luxury than by giving it; for by spending it in luxury you make them exert industry, whereas by giving it, you keep them idle.” The Enlightenment-era Scottish philosopher David Hume, meanwhile, wrote that “giving alms to common beggars is naturally praised; because it naturally seems to carry relief to the distressed and indigent: but when we observe the encouragement thence arising to idleness and debauchery, we regard that species of charity rather as a weakness than as a virtue.” Some even argued that ill-considered charity was the main problem in society; the Victorian economist William Stanley Jevons, for instance, claimed that “much of the poverty and crime which now exist have been caused by mistaken charity in past times.”

So indiscriminate charity was clearly seen as bad. (To the extent, indeed, that in Hamburg in 1788, a law was introduced which actually made it illegal to give alms indiscriminately!) But how does this relate to views about population? The answer is once again to be found in the work of Malthus, where indiscriminate charity is painted as an evil which contributes to the likelihood of population collapse by artificially enabling weak and unfit individuals to survive, and thereby undermining the natural (and necessary) weeding-out process that would otherwise take place. As Malthus rather uncompromisingly puts it (in a passage that even he thought sufficiently problematic that he removed from later editions of his book):

“A man is born into a world already possessed, if he cannot get subsistence from his parents on whom he has a just demad, and if the society do not want his labour, has no claim of right to the smallest portion of food, and, in fact, has no business to be where he is. At nature’s mighty feast there is no vacant cover for him. She tells him to be gone, and will quickly execute his own orders, if he does not work upon the compassion of some of her guests.”

This idea proved remarkably persistent. In the late 19th century the famed Economist editor Walter Bagehot wrote that “Great good, no doubt, philanthropy does, but then it also does great evil. It augments so much vice, it multiplies so much suffering, it brings to life such great populations to suffer and be vicious, that it is open to argument whether it be or be not an evil to the world.” An editorial in the Westminster Review, meanwhile went further in arguing that: “let the object be ever so undeserving, let him be a drunkard and a wife-beater… the prospect of alms withdraws this poor incapable from what work he could do, and the gift of them enables him to reproduce his kind; and the existence of such a class is a bane to society at large… Far better that such miserables should not come into the world, than that their sorrows should in this way be tempered by a little pleasure and comfort.”

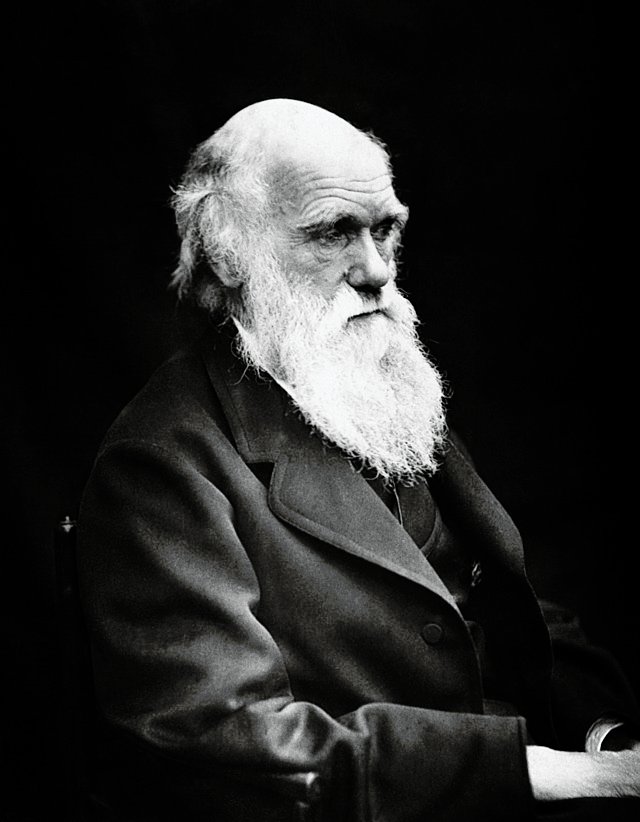

It is pretty clear from this that concerns about indiscriminate charity, in conjunction with Malthusian population theories, already carry us a long way along the road to eugenics. But the added ingredient that really accelerated things was the development of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Following the publication of his Origin of Species in 1859, many subsequently tried to adapt Darwin’s ideas to human society – with often problematic results. Indeed, Darwin himself put forward some pretty odious views in his later book Descent of Man (1871), where he argued that:

“With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. There is reason to believe that vaccination has preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed.”

Combined with better understanding of the mechanisms of genetic heredity, this ‘social Darwinism’ increasingly provided those concerned about population issues with the basis for ever-more active interventions, including compulsory birth control and forced sterilisation.

These sorts of ideas seem shocking to us now, but it is important to recognise that they were once widely accepted across society, to the extent that by the 1920s hundreds of universities were offering courses on eugenics. They were also enthusiastically adopted by many proponents of “scientific” philanthropy, who saw them as powerful new tools in their efforts to improve society. Women’s rights and birth control activists such as Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger were prominent promoters of eugenics. The philanthropist Ezra Gosney and the biologist Paul Popenoe, meanwhile, worked together for many years to promote and put into practice eugenic theories: firstly by advocating for sterilization, which they did through the rather chillingly-named Human Betterment Foundation, and then – when public support for such overt, proactive forms of eugenics waned – latterly by pushing pronatalist and family-oriented policy ideas through the American Institute for Family Relations (indeed, Popenoe, is still seen as one of the ley figures in the development of marriage counselling in the US). A number of far more well-known US philanthropic foundations were also involved in supporting eugenics research or the use of eugenic methods. The original funding for the Eugenics Record Office in the US, for instance, came from the Carnegie Corporation in 1910, while other foundations such as Ford, Rockefeller and Russell Sage supported similar efforts elsewhere.

The Chicago-based Wieboldt Foundation even funded a book on ‘Intelligent Philanthropy’ in 1930 that included contributions from a range of academic experts, including the notorious eugenicist H.S. Jennings. In his chapter on ‘biological aspects of charity’, Jennings suggested that:

“Charitable organisations are promoting the survival and propagation of the unfit … they are progressively filling the race with the weak and degenerate, who must hand on their weakness and degeneracy to their descendants. Conditions should be made harder instead of easier; any other procedure results in corrupting the race.”

Coming at a time when the Nazi Party was formulating its ideology in Germany – which would lead eventually to the atrocities and genocide of the Holocaust – these words in a book on philanthropy are deeply chilling. Yet much later in the twentieth century, there were still instances of philanthropic organisations being involved with highly problematic population theories and practice; in the late 1970s, for instance, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations were involved in funding programmes aimed at addressing overpopulation in India that are now acknowledged to have coerced many men to be sterilised against their will.

This relationship with eugenics is a dark stain on philanthropy’s past (as the philanthropy writer William Schambra has long argued e.g. in this 2013 piece, where he labelled it “philanthropy’s original sin”). Some organisations have begun to acknowledge and face up to this problematic history (e.g. the Rockefeller Archive has published some good material on its history with population issues and on its role in sterilisation campaigns in India), but there is still far more to be done. And this is not just about atoning for the sins of the past; we also need to heed this as a warning from history about the challenges we might face in the present as debates about population once more come to the fore.

Philanthropy and Current Population Debates

What then, if anything, can the historical context we have been considering tell us about the role that philanthropy is likely to play in current debates about population? The first, and most obvious, lesson is that there is not going to be any sort of consensus among donors or philanthropic organisations. The fundamentally pluralistic nature of civil society means that it will contains a range of individuals and organisations that reflects the spectrum of values and views you would find in society as a whole, so it should come as no surprise that we find donors and civil society organisations represented on all sides of the debates.

Some funders and NGOs may see their primary role as that of taking the heat out of population debates by trying to dissuade people from engaging in them in the first place, or by downplaying their importance. For instance Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (the public-private global health partnership) published an article in late 2022 which argued that the current population debate is “futile” and “misguided”; and that overpopulation fears are a “red herring”, whilst fears about declining birth rates are “unhelpful” and “often racist”. Bill Gates, meanwhile – who remains one of the world’s best-known philanthropists – has argued that a continuing focus on improving education and healthcare around the world will address concerns about overpopulation as an automatic corollary, because people will naturally choose to limit family sizes when infant mortality rates are lowered and birth control is more widely available. Discussions of active (and ethically questionable) measures to reduce population growth are thus unnecessary.

There are, of course, also NGOs and funders to be found much more clearly on one side of the debate or the other. In the “overpopulation is the problem” corner there are organisations like Population Matters in the UK, Population Connection, Negative Population Growth and GrowthBusters in the US, the Ten Million Foundation in the Netherlands, EcoPop in Switzerland, the Deutsche Stiftung Weltbevölkerung (DSW) in Germany, and the Population Foundation of India in India – all of which advocate for population control measures of one sort or another. And even where donors or foundations aren’t actually that strongly aligned with concerns about overpopulation, it is sometimes claimed by those on the other side of the debate that they are, simply because philanthropic funders make convenient bogeyman. In 2020, for instance, a piece of fake news did the rounds claiming that there is a sign on the outside of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that proclaims it the “Center for Global Human Population Reduction”, accompanied by a doctored photo of the building. (Which is certainly not the first time Bill Gates has been the target of a conspiracy theory, and is unlikely to be the last either).

In the “declining birth rates are the problem” corner there is a currently a smaller number of visible organisations. However, there are overtly pronatalist organisations like Pronatalist.org, whose founders Simone and Malcolm Collins have become poster children of sorts for a new pronatalist movement that has gained particular momentum within a community of wealthy, college-educated technology professionals. (The Collins couple have also been the subject of a number of profiles and articles in which they speak surprisingly candidly about their views, in terms that often stray into distinctly eugenics-sounding territory it has to be said). This new techno-pronatalist movement also includes a number of prominent philanthropists. Most notable among them so far is Elon Musk, who has spoken a number of times about his views that falling birth rates pose a danger to society and that wealthy, super clever people like him should be having more children to ensure that their lineages don’t get overly diluted by the rest of us proles and our progeny. (I’m paraphrasing slightly here, but in all honesty not very much – he really does appear to think this).

Musk’s prominence in this debate highlights another influence too: that of Longtermism. This is a school of thought which argues that we should base our thinking about present-day priorities on calculations about what is most likely to ensure the survival and flourishing of the human race over the very long term (using time horizons of hundreds or even thousands of years). Longtermism has come to be associated with the Effective Altruism movement (though the two are not the same) and has exerted a growing influence in recent years: particularly among wealthy tech types like Elon Musk (who has stated that Longtermism is a “close match for his philosophy”). One of the tenets of Longtermism, as outlined by the philosopher Will MacAskill in his recent book “What We Owe the Future” (which is the most prominent exposition of Longtermist thinking so far, and which you can find a Why Philanthropy Matters book review of here), is that it is an inherent good for there to be more human beings. As MacAskill puts it: “we should want future human populations to be happy. But we should also want them to be big.” And this idea gives an immediate intellectual basis for adopting pronatalist ideas in the present.

Of course, as we saw earlier, in practice pronatalism rarely occurs in a form that is agnostic about how the population grows. Instead, it often tends to be driven by fears that a particular group in society (of which the pronatalist is a member) is in danger of being outnumbered and therefore focusses on promoting methods of ensuring that more children are born to people within that group. These groups might be defined on a geopolitical basis (and there are certainly countries around the world, such as Hungary, which are currently promoting pronatalist policies to try to increase their own populations), but more often than not they are defined using supposed genetic or cultural characteristics such as race or IQ. And that takes us once again into the realm of pseudoscientific eugenics.

Those within Pronatalist movements, Longtermism and EA are usually at pains to distance themselves from any suggestion that they are sympathetic to eugenics. Most of the time this is fair enough: it is possible to have challenging views on population issues without necessarily being a eugenicist, and we need to be very careful about tossing that accusation around too freely. (To avoid any ‘boy who cried wolf’-style devaluation of the term, apart from anything else). However, that cuts both ways, and we also need to be strong in challenging those that do use the cover of rationality-driven schools of thought like Longtermism to espouse views that clearly veer into the territory of unfounded race science and eugenics.

And this is not just a theoretical risk – there have been a number of instance of it happening already. Most recently the philosopher Nick Bostrom (one of the key intellectual drivers of Longtermism) took the step of pre-emptively publishing an exchange from an email group in 1996, in which he made a series of deeply racist claims and used racial slurs. Bostrom’s ‘apology’ for the email was to many people’s eyes (mine included) totally unsatisfactory, as he focussed most of his efforts on trying to contextualise his specific use of language rather than addressing the underlying views being expressed, whilst at the same time also trying to defend the idea that expressing deliberately shocking views is a valid (and in his view valuable) intellectual tactic. (I personally hate this sort of defence of deliberately outré contrarian thinking, as it always seems to me to be the philosopher’s equivalent of the “it was just locker room banter” line of argument). Whether or not Bostrom is actually committed to the sorts of abhorrent views he expressed in his old emails, his comments and lacklustre apology have drawn sharp criticism – with some of the most acute coming from within the EA movement (see this thread from Chris Smith at Open Philanthropy for a sense of some of the critical responses from within EA).

It may seem surprising and shocking to many that individuals and organisations that are ostensibly philanthropic in nature are willing to flirt with such problematic views, but in many ways it is merely the most extreme example of more fundamental truth: that the pursuit of rationality and neat solutions to complex societal problems can lead people to lose sight of principles of basic humanity and respect for individual human lives. Indeed, it was a common satirical trope in the 18th and 19th centuries to paint “philanthropists” as high-minded idealists, whose focus on grand utopian schemes and disdain for “mere charity” sometimes led them to act in ways that seemed distinctly uncaring and even cruel. (For more on this, check out this previous Why Philanthropy Matters article on the history of satirising philanthropy).

Etymologically, of course, a “philanthropist” is a “lover of humanity”, but critics have long argued that this love of humanity in the abstract is not always accompanied by a love of actual real-life humans. A 1914 article in the Times, for instance, argued that:

“The philanthropist… often seems to overlook the individual in his passion for the general. Or rather he dislikes men because they fall short of his conception of what man ought to be. Man in the abstract and man whom it is his mission to love and to do good to would recognise his mission and submit to his good intentions, but concrete men persist in treating him just as if he were one of themselves. They do not offer themselves to his kind offices, and often they show resentment when these are thrust upon them.

Or, as the philosopher Robert Nozick put it in his classic 1973 book Anarchy, State and Utopia:

“Sometimes…one encounters individuals for whom the universal eradication of something has very great value while its eradication in some particular cases has almost no value at all; individuals who care about people in the abstract while, apparently, not having such care about any particular people.”

This empathy for humanity in the abstract is often accompanied by what political scientist James C Scott has termed the “High Modernist Ideology”, which he characterises as “a muscle-bound version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress, the expansion of production, the growing satisfaction of human needs, the mastery of nature (including human nature) and , above all, the rational design of social order commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws”. This combination can be seen in many of today’s Effective Altruists and Strategic Philanthropists, who emphasise the need to do away with subjectivity and emotion when it comes to giving and have a clear faith in the ability of technology to provide solutions or “hacks” for complex societal and environmental challenges. (Despite the fact, of course, that many of these issues are intractable and long-standing, and have proven resistant to the best efforts of government, philanthropy and the private sector in the past). A clear example is Elon Musk, who regularly describes his core motivation in hyper-utopian terms as “extending the light of human consciousness to the stars”, even though – according to multiple sources – he is notably lacking in concern for other people at an individual level. His brother, Kimbal Musk, has said of him that “he is a savant when it comes to business, but his gift is not empathy with people”, whilst the journalist Ashlee Vance, who wrote a biography of Elon Musk in 2015, said that “he doesn’t have a lot of interpersonal empathy, but he has a lot of empathy for mankind.”

If we move on from the more divisive aspects of population debates that we have been considering, there are of course other ways in which demographic trends are likely to have an impact on future philanthropy. One thing is that as population growth rates lead some countries and region to expand much faster than others, we are likely to see the centre of gravity of global wealth and philanthropy shift too. There has been a lot of discussion in recent years about the rise of China as a global philanthropic power, but with India set to overtake China as the world’s most populous country in 2023 (and Nigeria apparently set to overtake the US into third place in 2047) we will surely see new focus on these areas as well. And it would be arrogant to assume that the giving which emerges from these countries will simply mirror that of the US or UK; since each country has its own rich mixture of history, religion and culture that will more likely than not help to shape a unique philanthropic landscape.

The other key population-related factor that has profound relevance for philanthropy is life expectancy. At a societal level we are seeing the average age of populations around the world increase, as people live longer thanks to improvements in medicine and living conditions. At the same time, at an individual level, advances in technology have opened up the possibility that some of us may be able to extend our lifespans well beyond the limits of what nature would allow. (To the extent that the ageing expert Aubrey de Grey has even made the bold claimed that “the first person to live to 1,000 has already been born”). This combination of natural and artificial increases in life expectancy is likely to contribute to an ongoing increase in the average age of the population. While that may be great for those of us who stand to benefit from the possibility of more time on earth, it will also place a huge strain on our society and economy as we struggle to meet the health and social care needs an increasingly geriatric population (whilst at the same time, of course, the proportion of people who are of working-age presumably decreases). This is likely to present all sorts of new challenges for philanthropy to address.

Individual life extension is also likely to become an increasingly prominent focus for philanthropic spending. Now, personally, I don’t really know why you would want to live to 1000, but I suspect that it will prove popular among people who have made vast sums of money, simply because they seem more likely to have the requisite level of self-regard to think that the world would benefit from their extended continued existence. To that end, there are already a number of high-profile wealthy individuals, like Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel, who are supporting efforts to slow down the ageing process (through things like “young blood infusions”, which is just as weird and vampiric as it sounds) or to find ways of cheating death by cryogenically freezing themselves in the hope of being reawaken when future medical technology has advanced sufficiently, or by uploading a digital copy of themselves into a computer.

Obviously there is a high level of self-interest here, since the individuals in question presumably want to prolong their own lives; but if their donations or investments take the form of support for organisations that can benefit others, they will almost certainly be presented as philanthropic. This may well raise some challenging questions in the near-future about who actually benefits from such philanthropy, since if (as seems likely) life extension technologies are the sole preserve of the very rich, there is a clear risk of new forms of biological inequality emerging. (Just think the 1997 movie Gattaca as a shorthand).

What Next?

Population looks set to be a big issue for philanthropy in coming years. Both because the impacts of demographic changes will alter the nature of the challenges that we face as a society, and because philanthropists, funders and CSOs seem likely (based on historical and current evidence) to get increasingly dragged into debates about whether overpopulation or declining birth rates should be our primary concern (or whether both are in fact a distraction).

This is likely to bring more scrutiny of philanthropy and its influence on public policy and debate. It may also bring to light – and put further strain on – a tension that has long existed within philanthropy: between rational or head-driven, top-down approaches and more people-centred or heart-driven ones. Neither, of course, is an answer in itself, and philanthropy at its best always aims for a balance between the two. However, the murky history of philanthropy’s relationship with eugenics offers a stark warning about what can happen when you get this balance wrong.

If philanthropy is to avoid going down this ill-fated path once more, we must heed the warning of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who cautioned that, “it is not the slumber of reason that engenders monsters, but vigilant and insomniac rationality”; and we must not let over-confident rationality and abstract concern for humanity as a whole lead us to ignore the importance of basic human concern for the dignity and rights of individuals.