How does MacKenzie Scott’s approach to philanthropy fit within the wider history of big money giving?

8th October 2021

Mackenzie Scott has just made her latest announcement about the progress of her philanthropic efforts, detailing $2.9 billion (yes, billion) of grants to 286 organisations made in the first quarter of 2021. This comes hot on the heels of $4.2bn of grants announced in December 2020 and $1.9bn in July 2020.

As many have noted, it is not only the scale and pace of Scott’s philanthropy that is remarkable. (Though it goes without saying that it really is remarkable in both of those regards!) The way in which she is choosing to make grants is also eye-catching: with a clear focus on unrestricted gifts and long-term support. Furthermore, the narrative she is putting forward about her philanthropy — which speaks of shifting power and de-centering herself as a donor — marks a sharp departure from a lot of existing elite philanthropy (particularly that which comes out of the tech industry).

So what is different about MacKenzie Scott’s philanthropy? What should we be genuinely excited about, and where should we still be posing questions?

So what is different about MacKenzie Scott’s philanthropy? What should we be genuinely excited about, and where should we still be posing questions?

The Rejection of Received Wisdom

One thing that marks Scott’s philanthropy out, to my mind, is that she seems to be systematically rejecting many elements of received wisdom about the role of philanthropy and how it should be done. In doing so, her giving is not only having a direct impact on the organizations she is supporting, but is also posing a challenge to other ultra-wealthy individuals and elite donors. To understand this better, it is useful to look at the history of views about philanthropy, as this shows us where some of that received wisdom has come from and also highlights where Scott’s approach reflects past efforts to challenge and reform the philanthropic status quo. (NB: This builds on thoughts I laid out in an episode of the CAF Giving Thought podcast on “Mackenzie Scott and the Reimagining of Philanthropy” in 2021, so do check that out if you fancy an audio version…)

The myth of self-made wealth

One of the key things that Scott is challenging in how she describes her philanthropy is the notion that wealth is ever “self-created”. There has long been a belief held by some that becoming rich is a reflection of particular genius or hard work on the part of the individual in question, rather than reflecting accidents of birth, societal structures and the wider political and economic context of the time.

This has a major impact on philanthropy. For one thing, if you believe that your wealth is down to your efforts alone you are far less likely to buy into the idea that there is a social contract requiring you to give back to the society that made your wealth creation possible, so you are probably less likely to give in the first place. Secondly, if you believe wealth is solely the product of hard work then you also presumably believe the converse, i.e. that poverty is explicable as the result of people “not trying hard enough” or being somehow lesser (in a Darwinian sense); and as a result you are going to take a more judgmental view of the nature of poverty and the appropriate ways of addressing it. And thirdly, even if you do buy into the notion of philanthropic responsibility, you are more likely to do so in a way that seeks to maintain existing societal structures (on the basis that you have benefited from them, and so can others if they merely try hard enough), and which centres the role of the donor as the one who not only has the money, but also the solutions to social problems (of which more shortly).

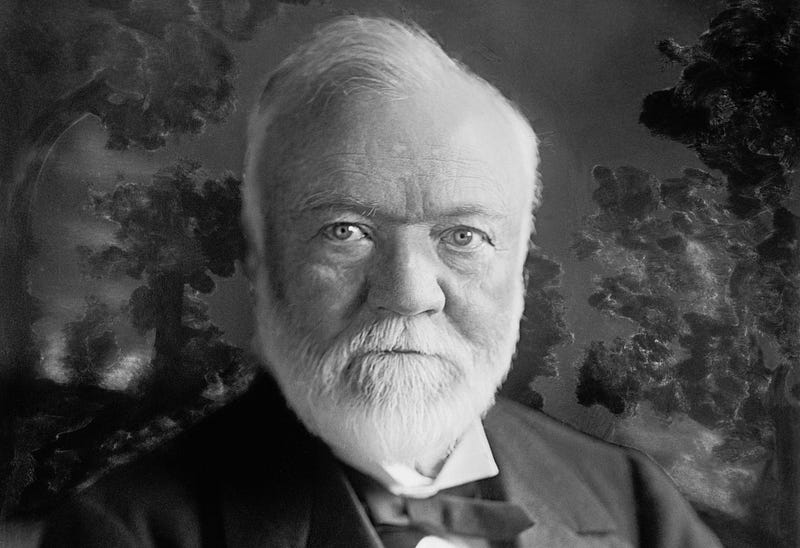

Andrew Carnegie played a major role in establishing this template through his writings, most famously in his “Gospel of Wealth”, where — following the social Darwinist ideas of Herbert Spencer (whom Carnegie counted as an intellectual idol) — he claimed that “it is a law… that men possessed of this peculiar talent for affairs, under the free play of economic forces must, of necessity, soon be in receipt of more revenue than can be judiciously expended upon themselves; and this law is as beneficial for the race as the others.” He further argued that this inequality and excess wealth was not something we should see as problematic because “not evil, but good, has come to the race from the accumulation of wealth by those who have had the ability and energy to produce it”.

In a similar vein (but even earlier), the Liverpool merchant William Rathbone VI wrote in 1867 that:

“Not only do we need that men of fortune should give of their wealth; we need much more that men of business should give of their brains, their power of organization, their knowledge of men and things, their business capacity and business habits. They have the talents that bring them to success in this world; and with those talents comes the temptation to devote them purely and solely to selfish aims; to make the utmost of them for purposes of worldly gain. It is earnestly to be wished that such men would practically acknowledge that they hold these talents as a trust from God, and are bound to use them in some part at least in the service of those to whom God has not given the advantages of position, education, connections, natural ability, or power of will, which have made them what they are.”

Even among those like Carnegie and Rathbone who believe that wealth creation signals some special capacity on the part of the individual, their views are often not clear-cut. Carnegie’s biographer, David Nasaw, for instance, argues that he did acknowledge the role that luck had played in his own wealth creation:

“Warren Buffett calls himself “a member of the lucky sperm club”. Carnegie made much the same point. He emphasised his good fortune in having moved to Pittsburgh with his family at precisely the moment the city was becoming a centre of iron and steel manufacturing because of its ideal location on the East-West railway network and its proximity to iron ore and coal deposits. Both men recognised that they had not earned their fortunes by themselves and thus had no right to spend them on themselves or on their families. As Carnegie put it, it was not any individual — talented and hard-working though he might be — but the community that was the true source of wealth. And it was to the community that the millionaire’s dollars should be returned.”

One thing that is clear is that both Carnegie and Rathbone believed wealth creation came with a responsibility to give back through philanthropy. However, their views about the desirable nature of this philanthropy do seem to reflect an underlying belief that wealth and poverty have a moral basis of sorts. So, for Carnegie (as indeed for many of his contemporaries), “indiscriminate” giving that failed to distinguish between those who were in poverty through no fault of their own and those who were there through laziness and lack of application was worse than no giving at all:

“Those who have surplus wealth give millions every year which produce more evil than good, and really retard the progress of the people, because most of the form in vogue to-day for benefiting mankind only tend to spread among the poor a spirit of dependence upon alms, when what is essential for progress is that they should be inspired to depend upon their own exertions. The miser millionaire who hoards his wealth does less injury to society than the careless millionaire who squanders his unwisely, even if he does so under the mantle of sacred charity.”

The notion of “self-created wealth” and the views that entails are still major factors shaping elite philanthropy today. This is especially true of the new breed of tech billionaires who are driving a lot of big giving, as Silicon Valley has a particularly strong mythos around wealth creation — centred on the image of the brilliant outsider who builds something in their shed that ends up disrupting an entire industry and thereby making them rich. (As I discussed with former Vox Recode reporter Teddy Schleifer in an episode of the CAF Giving Thought podcast). And this view often carries over into their philanthropy, which is likewise focused on finding disruptive (and usually tech-centred) “hacks” for intractable social and environmental problems, with power remaining firmly in the hands of the donor.

In reality, however, wealth is the result of a complex mixture of political, social and cultural factors, as well as — in most cases — a healthy dose of good old fashioned luck. Mackenzie Scott clearly believes this to be the case, as she has written that “There’s no question in my mind that anyone’s personal wealth is the product of a collective effort, and of social structures which present opportunities to some people, and obstacles to countless others.” This recognition of the structural nature of wealth (and, conversely, poverty) is a core element in her explanation both of why she feels it is necessary to give in the first place and the approach she is taking to her giving.

And she is not alone here: other philanthropists throughout history have similarly acknowledged the role that good fortune has played in their wealth accumulation and the fact that they have benefited from systems and structures that bring huge benefits to a small number of people but disadvantage many others. Julius Rosenwald, for instance, said:

“I believe that success is 95 per cent luck and 5 per cent ability. I never could understand the popular belief that because a man makes a lot of money he has a lot of brains. Some very rich men who made their own fortunes have been among the stupidest men I have ever met in my life. There are men in America today walking the streets, financial failures, who have more brains and ability than I will ever have. I had the luck to get my opportunity. Their opportunity never came. Rich men are not smart because they get rich. They didn’t get rich because they are smart. Don’t ever confuse wealth with brains. They are synonyms sometimes, but none too often.”

More recently Warren Buffett was similarly clear about the role that luck had played in his success:

“My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest. Both my children and I won what I call the ovarian lottery. (For starters, the odds against my 1930 birth taking place in the US were at least 30 to 1. My being male and white also removed huge obstacles that a majority of Americans then faced.) My luck was accentuated by my living in a market system that sometimes produces distorted results, though overall it serves our country well. I’ve worked in an economy that rewards someone who saves the lives of others on a battlefield with a medal, rewards a great teacher with thank-you notes from parents, but rewards those who can detect the mispricing of securities with sums reaching into the billions. In short, fate’s distribution of long straws is wildly capricious.”

Those who believe luck and structural factors play a role in wealth creation may still believe, like Carnegie, that the system we have on the whole benefits our society and that inequality is therefore merely a necessary price we pay. However many nowadays (MacKenzie Scott included) are more likely to believe that such inequality is problematic and needs to be addressed. This has further implications for how they view the role of philanthropy and the best way of engaging in it, as we shall see in a moment.

Power & Paternalism

Linked to the idea that wealth is self-made, and therefore a marker of particular genius or ability, is a belief that people who happen to be rich are also the best ones to identify the most pressing areas of social need and the best ways of addressing them. This often manifests itself in a fetishisation of “businesslike approaches”: Thorstein Veblen wryly noted as far back as the late C19th, for instance, that “business principles are the sacred articles of the secular creed, and business methods make up the ritual of the secular cult”. It has also led to a paradigm of philanthropy that has been dominant for more than a century, in which the goals and approach are set by the donor or funder and delivered to people and communities in need (presumably whether they like it or not).

There have long been criticisms that this kind of approach to giving is top-down, paternalistic and disempowering. As Susan Ostrander notes:

“Nearly a century ago, settlement house founder and progressive social scientist Jane Addams criticized what she called the “charitable relation… between benefactor and beneficiary” for its fundamental contradiction with democracy. This contradiction lies in Addam’s view of the charitable relation as one where benefactors give in accordance with their own interests, without the involvement of recipients in determining for themselves their major needs and interests. Addams explicitly labels this relation as hierarchical. Benefactors, she claims, retain superiority and power. The charitable relation takes place at the benefactor’s discretion, with the benefactor retaining the right to decide who is worthy of help and what kind of help is needed, without consulting the beneficiary”

There have been some philanthropists and funders who have tried to address these challenges and to make their own approach more democratic, such as the Stern Family Fund (established by Julius Rosenwald’s daughter Edith Rosenwald-Stern) or the Haymarket People’s fund. Throughout most of history this has been only a marginal part of philanthropy, but more recently there has been an upsurge of interest in exploring new models and methods that move the emphasis from the donor to the recipient, and which seek to shift power as well as resources. Participatory grantmaking is perhaps the most prominent of these; and whilst rhetoric still outstrips action to some extent, there are many funders starting to experiment with participatory methods (as I discussed in an episode of the CAF Giving Thought podcast with Meg Massey and Hannah Paterson).

It is clear that this desire to make philanthropy more democratic is an important part of what informs MacKenzie Scott’s approach to giving. In her announcements to date she has been keen to emphasise that whilst she has money, this does not mean she is best placed to decide how it should be deployed. And she is not afraid to position this as a particular strength of her approach, arguing that, “I began work to complete my pledge with the belief that my life had yielded two assets that could be of particular value to others: the money these systems helped deliver to me, and a conviction that people who have experience with inequities are the ones best equipped to design solutions.”

But whilst Scott’s approach is clearly very empowering for the organisations she supports, with funding offered in the form of core-cost grants with few strings attached, there is still a question as to how those organisations are selected in the first place. As we will see, this is one area where some have been lightly critical of Scott; arguing that greater transparency about how funding decisions are made and the identity of the team of advisers she is relying on to help her make choices would be welcome. Just as there is a power imbalance in the traditional relationship between donors and recipients that needs to be addressed, there is also significant power in the ability to choose which organisations to engage with, and this needs to be acknowledged too.

This is particularly important when it comes to supporting grassroots organisations and social movements, which MacKenzie Scott clearly wants to do. In this case, many of the potential recipient organisations have very limited resources, so the support of a funder like Scott can be totally transformative — not only for the organisation itself, but for the wider field in which it works, because the scale of the funding in relation to that wider field may have a distorting effect. This is why understanding how choices are made about what to fund and why is so important (and conversely why understanding why other organisations did not receive funding is equally vital). As Daniel Faber and Deborah McCarthy argue in their introduction to their edited collection “Foundations for Social Change”:

“Many foundations engage in the philanthropic exclusion and/or marginalization of select organizations for social change within normally funded popular movement. In other words, when foundations do fund social movements, they often encourage and support the more politically “centrist” organizations and campaigns within movements. Larger foundations have a greater capacity to “disembody” and “conventionalize” a movement, although networks of smaller foundations acting in a coordinated fashion can have the same type of impact.”

There is nothing so far to suggest that MacKenzie Scott is either deliberately or accidentally “taming” any of the social movements she is supporting. However, given that this is a danger that scholars of philanthropy and social movements have long acknowledged (e.g. check out this 2019 interview I did with Megan Ming Francis for the CAF Giving Thought podcast about her work on “movement capture”), it is something that Scott and her advisers need to guard against, and greater transparency would help them to do so.

Does “strategic” have to mean top-down/technocratic?

One of the major challenges MacKenzie Scott is posing with her giving, to my mind, is to our dominant notions of what it is to be “strategic” or “effective” when it comes to philanthropy. This links to what has already been said about the mythos of wealth creation and donor-centred approaches to giving, as many of our current notions of what it is to be strategic or effective are based on a model in which the donor or funder defines both the goal and the approach/intervention used to deliver it. “Success” is then assessed based on the extent to which the approach proves to be effective (using methods of measurement most likely also defined by the donor/funder).

But what of an approach like MacKenzie Scott’s, which aims to move away from top-down, donor-directed programmatic funding towards more flexible, trust-based core funding? In handing over the power to make decisions about how money is spent to recipient organisations, and making few if any demands of them in terms of measurement, is Scott sacrificing being strategic in pursuit of a desire to make her giving more democratic? That’s certainly what some have claimed, arguing that whilst her approach to philanthropy may be laudable in itself, it remains to be seen whether it is “effective”.

One immediate rejoinder to this line of criticism is that it implies a rather depressing lack of faith in the work of nonprofits and activist groups. If Scott is willing to place trust in these organizations by giving them longer-term core funding, on the basis that they almost certainly know better than her how to use the money to address the issues they work on, why should that be seen as any less “strategic” than designing and building her own programmes and interventions, or giving highly prescriptive grants based on her own views about how best to address societal challenges?

In any case, it is not like Scott is simply throwing handfuls of cash out of a moving car window in the hope that it finds its way into the hands of someone able to do good with it; in actual fact there appears to be a lot of research and due diligence going on. The difference is that this work is going on prior to the engagement with grant recipients, rather than being imposed upon them. As Scott herself explains:

“We do this research and deeper diligence not only to identify organizations with high potential for impact, but also to pave the way for unsolicited and unexpected gifts given with full trust and no strings attached. Because our research is data-driven and rigorous, our giving process can be human and soft. Not only are non-profits chronically underfunded, they are also chronically diverted from their work by fundraising, and by burdensome reporting requirements that donors often place on them.”

Now, if you are really looking to be critical, there could be an argument that this approach actually takes some of the power out of the hands of civil society organisations because it limits their ability to make a case for their work through fundraising and donor engagement. However, when faced with the philanthropic equivalent of unsolicited manna from heaven in the form of a large no-strings-attached grant, I suspect few non-profit organisations would be raising such quibbles…

The other point to be made about criticisms that Scott’s approach is not “strategic” or “effective” is that they may beg the question of what she is trying to achieve. They seem to assume that handing over power to grantees is part of an approach designed to achieve some other goal or outcome, but what if that empowerment is the goal? What if Scott’s primary purpose with her philanthropy is to shift power to those she is supporting and to challenge existing paradigms of grantmaking? If so, what she is doing is surely both strategic and effective.

The idea that we should strive to make philanthropy more “strategic” or “rational” has a long history. In the late 18th and early 19th century critics argued that the principles of political economy should be applied to charitable giving, whilst in the late 19th and early 20th century the Charity Organisation Society and Scientific Philanthropy movements demanded that giving be based on more rigorous principles of evidence and investigation that mirrored the methods of science. More recently, some have argued that philanthropy can be improved by making it more “businesslike” and following the logic of the market, whilst advocates of Effective Altruism propose a radical new rationality for giving based on a utilitarian vision of maximising good for the greatest number (whilst remaining agnostic about cause areas).

Each of these normative efforts to ‘impose order’ on philanthropy has met with resistance from those who feel that in seeking to replace the element of “heart” entirely with that of “head”, the reformers have misunderstood the fundamental nature of giving and the human impulses that drive it. This is sometimes characterized as a battle between ‘charity’ and ‘philanthropy’, or between ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ approaches to giving. The social reformer Josephine Butler, for instance, adopted this language in calling for a middle-way approach between these two poles:

“We have had experience of what we may call the feminine form of philanthropy, and individual ministering, of too mediaeval a type to suit the present day. It has failed. We are now about to try the masculine form of philanthropy — large and comprehensive measure, organizations and systems planned by men and sanctioned by Parliament. This will also fail if it so far prevails as to extinguish the truth to which the other method witnessed in spite of its excesses. Why should we not try at last a union of principles which are equally true?”

A distinctive element of MacKenzie Scott’s narrative about her own giving — which perhaps echoes this idea of a “feminine” approach to philanthropy — is that she seems keenly aware of the importance of human connection and is unafraid to emphasise it. In the Medium posts announcing her second tranche of grants she wrote:

“We shared each of our gift decisions with program leaders for the first time over the phone, and welcomed them to spend the funding on whatever they believe best serves their efforts. They were told that the entire commitment would be paid upfront and left unrestricted in order to provide them with maximum flexibility. The responses from people who took the calls often included personal stories and tears. These were non-profit veterans from all backgrounds and backstories, talking to us from cars and cabins and COVID-packed houses all over the country — a retired army general, the president of a tribal college recalling her first teaching job on her reservation, a loan fund founder sitting in the makeshift workspace between her washer and dryer from which she had launched her initiative years ago. Their stories and tears invariably made me and my teammates cry.”

In doing this, is she trying to reintroduce some elements of what might in the past have been pejoratively labelled “charity” into our understanding of philanthropy? Or, as Paul Vallely frames it in his book Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg, to bring together the “strategic” and “reciprocal” approaches to philanthropy? (You can hear me discuss this with Paul at length on a 2020 episode of the CAF Giving Thought podcast).

Pace, Perpetuity and Pledges

Andrew Carnegie famously said that “it is harder to give money away intelligently than to earn it in the first place”, and this is often cited in support of a view that giving large sums is frightfully difficult and therefore must be done slowly, in a heavily restricted way, over long time periods. (BTW I’m not deliberately just picking on Carnegie here- it’s just because he has been so influential in shaping modern philanthropy so it is kind of unavoidable!)

But again, this is an idea that Scott is challenging through her philanthropy. For one thing, the pace of it is quite remarkable. To give away $9bn in little over a year is absolutely unprecedented; and whilst (as outlined above) there may be some critics who would contend that she is not doing it “intelligently” or “strategically”, the fact that her approach has enabled her to operate at this speed is, for many, a strong argument in its favour.

The time horizon Scott is applying to her philanthropy also offers a challenge — this time to the idea of perpetual endowment. It has been a default assumption of philanthropy for many hundreds of years that it should involve the creation of structures that exist in perpetuity, beyond the life of the donor. This became prominent as an issue during the early 20th century with the birth of many of the US mega-foundations, but it has been a source of criticism for far longer. In the 18th century, for instance, the French economist Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot wrote that:

“Public utility is the supreme law… it must not be tempered by a superstitious respect for the so-called intentions of the founder as if individuals, ignorant and limited as they are, have the right to subject unborn generations to their caprice… Let us conclude that no work of man is made for eternity; and since foundations, continually multiplied by vanity, would ultimately absorb all wealth and private property, we must be able to destroy them.”

In the early 20th century, meanwhile, Julius Rosenwald said more succinctly that he was “opposed to gifts in perpetuity for any purpose”. But MacKenzie Scott is not just in good historical company in rejecting the idea of perpetuity in her philanthropy; here she is part of a wider contemporary trend towards giving while living and making philanthropy time-limited. Like other signatories to the Giving Pledge, Scott is committed to giving away at least half of her wealth in her lifetime. (Although it should be said that she appears to be getting on with making that happen rather quicker than many others on the list…)

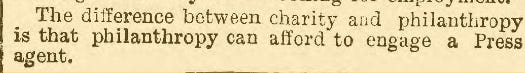

Mention of the Giving Pledge brings us to the final way in which MacKenzie Scott is going against the grain with her philanthropy. It has become standard practice among big donors (especially those from the tech world) to make big announcements about their intentions rather than their actions. The Giving Pledge is the prime example of this, and whilst it has won plaudits for the commitments it has garnered from many wealthy people around the world to give back in a big way, there has also been criticism that this is not accompanied by any mechanisms to track that giving or to hold signatories to account. In a similar vein, Scott’s former husband Jeff Bezos made headlines back in early 2020 when he announced that he was going to give $10bn to establish a new fund focussed on climate issues. Details of what Bezos is actually doing to realise this promise have been slow to emerge; and in the meantime Scott has managed to give away nearly as much as the amount he pledged already. Which is not to say that pledges to give are not a useful tool for developing norms and creating healthy peer pressure among the ultra-wealthy, but we do have to be careful that the announcement of the intention to give does not become the end in itself. (I’m reminded here of an aside I found in a 1905 copy of a newspaper from West Wales, that “the difference between charity and philanthropy is that philanthropy can afford to engage a Press Agent”…)

The Grit in the Oyster

It is probably more than apparent from what has been said that I think MacKenzie Scott’s approach to philanthropy and her actions over the last year are both fascinating and hugely impressive. In many ways it can be argued that she is providing a template for what a positive vision of philanthropy in the 21st century might look like. However, we shouldn’t pretend that it is all entirely sunshine and lollipops. There are certainly critiques and questions still outstanding, of which (to my mind) the key ones are:

- Will Scott’s approach prove to be effective? There are some who argue that we should reserve judgment about Scott’s philanthropy until it is possible to know whether it proves to be effective or not. (As covered at length above, this depends largely on what you assume her goal to be and what your criteria for assessing “effectiveness” are).

- Transparency: Many have called for more transparency about who Scott’s advisers are and what criteria they are applying in deciding who to fund. Others have pointed out that whilst Scott publishes lists of the organisations she funds, she does not specify the amounts given to each- which would be useful information in understanding the overall picture of her giving and in informing the activities of other philanthropic funders.

- Distorting effect on the nonprofit sector: Some have argued that no matter how well-intentioned and carefully thought-out Scott’s approach to giving may be, philanthropy at this scale cannot help but have a distorting effect. Scott’s giving now makes up a significant proportion of the total philanthropic funding for US nonprofits, so the decisions she makes about who to fund (and who not to fund) have a major impact — both on the nonprofits themselves, and potentially on other funders who may be considering funding in similar areas.

- Part of the problem, not part of the solution: Critics of big philanthropy have argued that the fact Scott is able to give at this scale should be seen not as a cause for celebration, but as further evidence of how big a problem wealth inequality is. This is by no means a new point, and from Scott’s pronouncements it would seem as though she agrees to a large extent that her level of wealth is problematic, but some would like to see her go further by supporting calls for wealth taxes, funding labor rights organizations etc.

- Amazon wealth is tainted wealth: Plenty of critics would further argue that the fact Scott’s wealth comes from Amazon makes it particularly problematic, given the company’s well-documented history of tax avoidance and its poor record on labour rights and treatment of its employees. It is easy here to paint Scott as the passive recipient of this money, or as a heroine who has taken the money from Jeff Bezos via a divorce settlement and is now, Robin Hood-like, redistributing it to the poor. However, this is probably a mistake. For one thing, as this Marker piece details, Scott was far from being a passenger in the development and growth of Amazon (certainly in the early days, at least); and for another it is somewhat patronising to absolve Scott of any need to take into account how her wealth was created and what that might mean for the legitimacy of her efforts to do good through giving it away. All donors at this kind of scale need to contextualise their philanthropy in that way, and Scott is no different in that regard.

So where does this leave our assessment of MacKenzie Scott? Is anything she is doing genuinely new? Perhaps not, in the sense that each individual element has historical precedents (as they almost always do!) However, by combining these elements (some of which have only ever been fringe parts of philanthropy at best) and doing so at a scale that commands such widespread attention, she does appear to be doing something unprecedented. And, in broad terms, should we welcome what she is doing, or be more sceptical? Here, I definitely err on the side of the former. Whilst we should continue to subject Scott’s philanthropy to scrutiny (as we should with all giving at this scale), there is a great deal to applaud about her approach so far. The way she talks about her philanthropy also suggests that she recognises many of the challenges and critiques people are posing and is adapting in light of them.

I will leave the final word to MacKenzie Scott herself. In the announcement of her latest tranche of funding she has the following to say, which for my money gets to the heart of the challenge she is posing to our dominant paradigm of philanthropy and why that has to be seen as a positive thing:

Putting large donors at the center of stories on social progress is a distortion of their role. Me, Dan, a constellation of researchers and administrators and advisors — we are all attempting to give away a fortune that was enabled by systems in need of change. In this effort, we are governed by a humbling belief that it would be better if disproportionate wealth were not concentrated in a small number of hands, and that the solutions are best designed and implemented by others. Though we still have a lot to learn about how to act on these beliefs without contradicting and subverting them, we can begin by acknowledging that people working to build power from within communities are the agents of change. Their service supports and empowers people who go on to support and empower others.