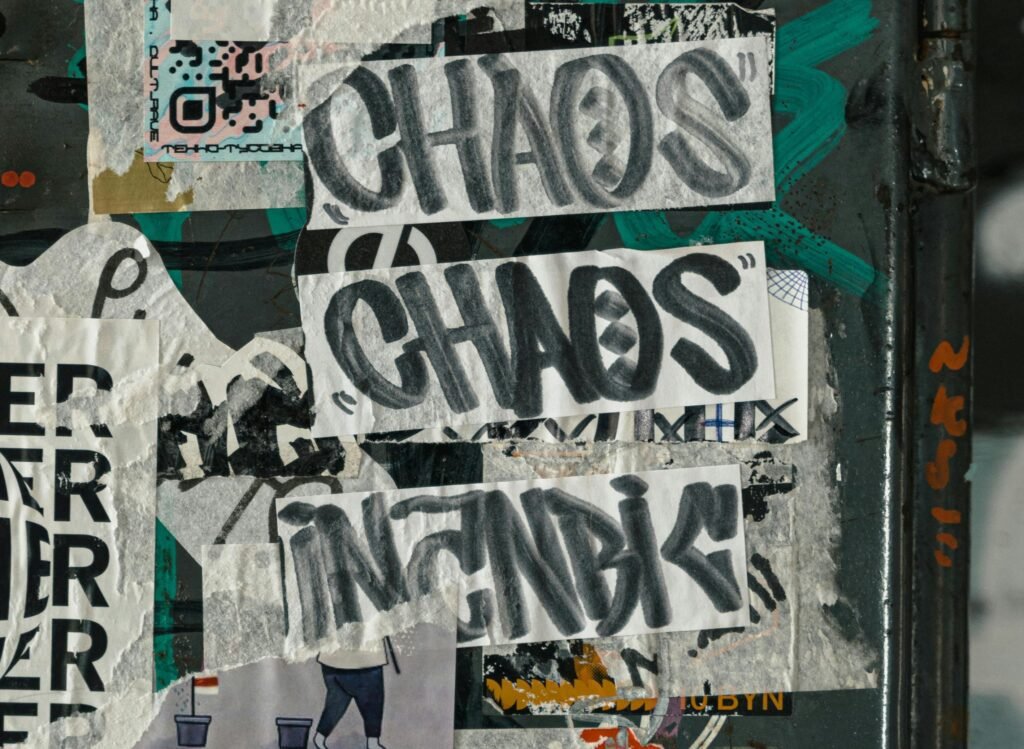

Following a barrage of executive orders and policy announcements from President Donald Trump which posed major challenges for civil society organisations, we take a look at some of the key questions for philanthropy at a time of chaos.

10th February 2025

The first few weeks of Donald Trump’s 2nd term as president have been chaotic, horrifying and absolutely exhausting – even as someone only watching from the opposite side of the Atlantic. Just as everyone is desperately trying to get their head around the implications of slapping trade tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China, Trump holds a press conference and declares that the US is going to solve the situation in Israel-Palestine by “taking over the Gaza Strip”. Meanwhile the Other President – unelected billionaire man-child Elon Musk – is spearheading what looks increasingly like a deliberate coup; taking control of the systems the US Treasury uses to make payments and implying that he will cut off any individuals or organisations who don’t demonstrate sufficient loyalty to the new administration.

These are worrying times for many in the US, and in other places around the world. And there are particular challenges for civil society organisations right now, as a number of the executive orders signed by President Trump will have a direct – and in some cases devastating – impact on their work. A proposed freeze on federal grant funding – which was temporarily blocked by legal challenges (and perhaps rescinded for now) – would see thousands of nonprofits lose major funding streams, and the people and communities they work with suffer greatly as a consequence. Meanwhile the grotesquely gleeful efforts of Elon Musk to dismantle USAID, the world’s biggest humanitarian agency, are already causing huge harm to communities around the world that are struggling with the impacts of food shortages, famine and war (as the many worrying reports already coming in from sources on the ground are attesting). At the same time, the decision to withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Agreement is posing major challenges for environmental funders and non-profits, and the all-out assault on DEI initiatives is likely to make life very difficult for organisations that target their work in any way to address historic injustices and inequalities.

Amidst all this chaos, what of philanthropy? What should donors and funders be doing? And what particular challenges might they face? In this article I want to outline some thoughts on these questions, in the hope that me thinking out loud and getting things clear in my own head is useful to others (even if I can’t necessarily claim to have any answers).

The confusion and the cruelty IS the point

The first thing to remember is that whilst the barrage of news and comments coming out of the Trump administration right now might well feel hard to deal with, that’s precisely the point. Whilst a lot of what is being said may sound totally unhinged – and to some extent that reflects the fact that the people saying it are dangerously unhinged – there is also a clear strategy at play: to flood the space with so much noise that everyone feels overwhelmed and they aren’t able to fight back effectively, so the things the administration and their friends are actually serious about get through without much opposition.

As the sociologist Jennifer Walter said in a post that was doing the rounds on LinkedIn and Bluesky:

“Your overwhelm is the goal… The flood of 200+ executive orders in Trump’s first days exemplifies Naomi Klein’s “shock doctrine” – using chaos and crisis to push through radical changes while people are too disoriented to effectively resist. This isn’t just politics as usual – it’s a strategic exploitation of cognitive limits.”

It’s akin to how a magician will try to distract the audience so they don’t focus on what he is doing with his hands. (Although for the full effect, instead of light-hearted stage patter, imagine that the magician is instead spewing out a steady stream of hate-filled invective and racial dog-whistles). And just as experts will tell you that if you want to see how a magic trick really works, you need to ignore what the conjuror is saying and just watch his hands; when it comes to the new Trump administration it feels like part of the trick will be to avoid getting sidetracked by all the ridiculous things they are saying and focus instead on what they are actually doing.

A lot of the advice being offered on how to navigate the current chaos centres on this kind of idea. The aforementioned post from Jennifer Walter, for instance, suggests as actions the following:

“1. Set boundaries: Pick 2-3 key issues you deeply care about and focus your attention there. You can’t track everything – that’s by design. Impact comes from sustained focus, not scattered awareness.

2. Use aggregators & experts: Find trusted analysts who do the heavy lifting of synthesis. Look for those explaining patterns, not just events.

3. Remember: Feeling overwhelmed is the point. When you recognize this, you regain some power. Take breaks. Process. This is a marathon.

4. Practice going slow: Wait 48hrs before reacting to new policies. The urgent clouds the important. Initial reporting often misses context

5. Build community: Share the cognitive load. Different people track different issues. Network intelligence beats individual overload. Remember: They want you scattered. Your focus is resistance.”

This is good advice that we should all heed, but we also need to be aware that following it may be easier said than done. Particularly when it is not just the volume of communication coming out of the Trump administration right now that is the problem, but the tone – which seems deliberately calibrated to goad progressives and other political “enemies”. Now, I’m definitely willing at this point to believe that Elon Musk’s tweets about “feeding USAID into a wood chipper” and accusing it of being a “criminal organisation” are a clear reflection of the fact that he is just an awful, awful human being. But I also suspect that there is a strategy at play here, and that the glib cruelty and callousness on show is designed as a form of trolling (which Musk and Trump certainly both have long track records of); where the aim is to make people who might oppose them outraged, and thus less able to keep the necessary calm focus on what needs doing.

The challenge here is that the correct response to unelected billionaires gleefully making unlawful decisions that are likely to cause huge harm and loss of life around the world is outrage, so it is quite hard to contain this impulse. And to some extent, we shouldn’t: if ever there was a time to be outraged and angry, this is probably it. The trick, of course, is not to let this outrage become overwhelming or to expend it entirely spent on furious social media denunciations (although some of those are OK – we are all human, after all), but instead to find ways of harnessing it as the fuel that drives concerted and coordinated actions in response. And this is true for philanthropists and funders, in the same way that it is true for the rest of us.

Covering the gaps?

The first big question for philanthropic funders is what to do about the sudden, massive withdrawal of government funding for civil society. The answer may seem obvious – “step in and cover the gaps” – but in reality it is more complicated than that. For one thing, it just isn’t practically possible for philanthropy to fill all the gaps that will be left by the destruction of USAID or the withholding of federal grant funds in the US. Even the biggest of Big Philanthropy pales into comparison relative to the scale of government finances: Bill Gates has said previously that philanthropy is “a rounding error” in the context of public spending, and Michael Bloomberg declared back in 2014 that “all the billionaires added together are bupkis compared to the amount of money that government spends.

(As an ironic sidebar, perhaps the one man who could test this theory is Elon Musk, since his estimated $426 billion fortune is greater than the GDP of all but the top 34 nations on Earth, so if he decided to give even half of it away, he would be operating on the same scale as governments. But that clearly isn’t going to happen, as he has never really shown any interest in philanthropy, and he now seems more set on decimating civil society rather than doing anything to support it).

Of course, even if philanthropy can’t cover all of the gaps left by the large-scale withdraw of government funding, it can cover some of them – and plenty of donors and funders will feel compelled to try. This raises a couple of important questions. The first being: what else might not get funded as a result? Since the pool of philanthropic capital is finite (and has generally proven stubbornly resistant to significant enlargements), presumably any funding that is used to replace lost government funding would have to be diverted from other current or future projects which may bring significant opportunity costs. The second, perhaps more fundamental, question is: even if philanthropic funders can cover some of the gaps, should they? Some would argue that this might actually make the problem worse, by ameliorating the impacts of the government’s decisions and thus letting them off the hook to some extent. This is definitely a valid line of argument in theory, but it is harder to see how it works in practice if it requires funders to make a conscious decision not to fund work that has clear value or meets immediate needs, in the hope that the consequences of not doing so are sufficiently bad that the Government is forced to change course. For one thing, those consequences may well include lives being lost that could otherwise have been saved, and it is difficult to see how a philanthropic funder could make a moral case to themselves that this is an acceptable price to pay. Furthermore, for this kind of strategy to work, we have to assume that the government actually cares about the potential negative impacts, or would feel shame at them, but I’m not sure that applies in this case. Unlike the situation in which a government cuts back spending in the hope or expectation that philanthropy will step in (as we have often seen in the case of the arts, for example), the decisions taken by the Trump administration largely target causes and organisations that they would probably rather didn’t exist at all, so they have no real interest in philanthropy picking up the slack and presumably would feel little or no shame if that didn’t happen. (And in any case, an inability to feel shame increasingly seems to be one of the key attributes of successful politicians…)

The challenge might actually be even bigger than this, as funders and nonprofits who step in to replace government funding for civil society that has been lost as a result of Trump’s executive orders may find themselves confronted not merely by the indifference and lack of shame of an administration that doesn’t care about the impacts of its decisions, but by deliberate attempts to demonise them. Some within the administration (most notably Vice President J.D. Vance) have already made clear their antipathy towards philanthropy (particularly large, progressive foundations), and almost certainly wouldn’t waste a second in accusing any funder who stepped in to cover gaps in withdrawn government funding of being “antidemocratic” and “part of the problem”. Funders will therefore have to decide if they are willing to take this risk and face such criticisms head on. (We’ll come back to some of the challenges that the Trump government might pose to philanthropy itself in a moment).

Defending civil society

The next big question for philanthropic funders is what role they are going to play in supporting the defence of civil society values and organisations, above and beyond covering immediate funding gaps.

Should they, for instance, be pivoting to support legal challenges to the Trump administration’s policies and executive orders, of the kind that the National Council for nonprofits launched against the federal grant funding freeze, and which resulted in the implementation of the order being temporarily halted (before it was seemingly dropped altogether)? If so, how do they do this in the most strategic way, so that it doesn’t simply end up being a reactive game of whack-a-mole that absorbs all their financial resources and time? (Since legal proceedings are not famous for being either quick or cheap). And what happens if it turns out the Trump administration decides to just, well… ignore the courts? (Obviously at that point we are talking about a pretty fundamental challenge to the basis of democracy, but it definitely doesn’t seem that far-fetched).

Or perhaps the whole point is that funders don’t need to be “strategic”, and that this is instead a time to lean even further into placing trust in organisations on the ground by offering them unrestricted funding? CSOs of all kinds have long argued that this kind of funding is preferable, because it puts the power in their hands to choose how money is used, and at a time of chaos – when it is may well be necessary to change plans rapidly – it is more important than ever that funders recognise this. This may test the risk appetite of some funders, especially since the heightened politicisation of the civil society arena means that there is a greater chance the activities of organisations they fund will come in for criticism from political commentators. The response to this threat, however, should not be to revert to placing restrictions on funding and thus tying the hands of grantees at a time when they need all the freedom they can get. Instead, funders need to be bold. After all, as the Director of the Carnegie UK Trust said back in 1952 “It is the business of Trusts to live dangerously”.

When it comes to being willing to fund work that is “political” in nature, funders may not even have a choice anymore. Racial justice work of any kind, for example, is likely to fall foul of the Trump administrations “war on DEI”, so funders that support this kind of work will have to make a choice as to whether to continue to fund it (and potentially be accused of acting inappropriately “politically”), or to back off. We are already seeing a wide range of for-profit companies that went big on DEI row back their commitments, but for nonprofits whose mission and values are aligned with racial justice, this kind of capitulation isn’t really an option. And this doesn’t just apply to issues such as racial justice (which have always been fairly political in nature): by threatening to destroy the apparatus of USAID, and forcing funders and nonprofits to make a choice to step into the breach in opposition to government policy, the administration has arguably politicised basic human compassion. Even organisations that see their role entirely in service delivery terms may have to accept the risk of being accused of acting “politically” if they are to continue providing those services and delivering on their mission.

So, I’m not sure that anyone really gets to stay out of politics right now, and philanthropic funders will need to adapt to this new reality. At the same time, it will be important keep one eye on longer-term ambitions of repairing and renewing civic space, which many funders and nonprofits have been working on in recent years. The challenge that funders and nonprofits may find, however, is that if they lean too heavily into their role as political adversaries for government, it will exacerbate existing issues of polarisation and make it harder to achieve these longer-term goals. This should absolutely not be taken as a veiled suggestion that I think it would be better to keep quiet or to go along with the government’s actions in the hope that this will avoid friction and automatically lead to some kind of magical democratic renewal, because I don’t. I think that would be remarkably naïve at this point, given that the government themselves have given no indications that they have any interesting in reducing polarisation and strengthening civic life (in fact, quite the opposite). So it is largely just a matter of pragmatic reality that funders and nonprofits will almost certainly have to accept a more adversarial role over the short term; but I do think it is important to be aware that this may come at a cost in terms of making longer-term aims of repair more difficult to achieve.

The other challenge that some funders and nonprofits will face is that they may in the past have been critical of the very systems and structures they are now called upon to defend. Take USAID, for example: it undoubtedly does a vast amount of good work around the world, which is why the efforts to destroy it have been met with such shock and revulsion. But plenty of critics (including nonprofits and funders) have pointed out its flaws as well – accusing it of being overly bureaucratic or failing to make sufficient efforts to localise its distribution of aid. Similarly, many racial justice campaigners have criticised the notion of DEI for being too surface-level and allowing organisations to engage in performative concern about racial justice without actually doing any of the hard work necessary to deliver it. So how do these critics react now that the things they criticise are under attack? Presumably most of them will still rally to the defence of USAID or DEI policies, on the basis that even if they are flawed that doesn’t mean we should abandon them altogether. And that is a perfectly valid line to take, although it can be a difficult one to sell. One of the lessons of the campaign prior to the 2016 Brexit vote in the UK is that when you have one side offering a clear argument that “thing X is bad, and we should get rid of it” (as the Leave campaign said about the European Union) and another side offering an argument that “thing X definitely isn’t perfect, but it’s better than not having thing X, so we should stick with it and try to reform it” (which was the basic gist of the lacklustre Remain campaign), the former tends to cut through more effectively. So those who have been critical of USAID or DEI in the past will need to figure out what approach to take: do you argue in their defence, but offer caveats? (Which might not be that helpful). Or do you dial down any criticisms in the interests of keeping the message clear, but then risk romanticising what has gone before (or face accusations of hypocrisy)?

Defending philanthropy?

Philanthropists and funders clearly have a role to play in supporting civil society organisations to defend themselves and their values against government attacks, as we have seen. But philanthropy itself may also need defending – both from government and, perhaps, from philanthropists themselves.

In the run-up to the 2024 Presidential election, now Vice President J.D. Vance made clear his antipathy towards philanthropy – particularly in the form of large, progressive foundations (which he has called “cancers on US society”). Some at the time questioned whether this rhetoric would be forgotten when the new administration came to power and they had other priorities to deal with, but whilst it has not yet been that overt part of the attacks on civil society, it certainly doesn’t seem to have gone away. So, as foundations work out how best to support civil society, they need to be braced for attacks on their own legitimacy – including, potentially, criticism of individual people working within foundations (as Musk has certainly been happy to do in the case of government staff).

There are two particular challenges I can see here: the first is how to defend philanthropy without it simply seeming like self-interest or preservation of the status quo. Some observers have wryly noted that in the past, funders often seem to have mobilised significantly more quickly and effectively when their own tax or legal advantages have been threatened, as opposed to when there is a crisis of acute need that requires their attention. This may be slightly unfair, but it is certainly true that any defence of the privileges that philanthropic donors and funders have which doesn’t make a clear and compelling case for why those privileges are justified and necessary risks coming across as self-defence (and may struggle to win support from wider civil society as a result).

The second challenge for philanthropic funders is that J.D. Vance is not alone in holding a critical opinion about philanthropy – indeed, some of his views may even be shared by parts of the civil society sector. Organisations aligned with the political right, such as The Philanthropy Roundtable, may be willing to go along with populist attacks on progressive philanthropy for ideological reasons (even if this might end up harming philanthropy as a whole). But it is also worth noting (as a recent piece in Inside Philanthropy pointed out) that some of Vance’s suggestions for how to deal with the problems of elite philanthropy (as he sees them) are eerily similar to calls for reform being made by progressive groups on the left of the political spectrum such as the Donor Revolt for Charity Reform. There is a clear difference in motivation and intent (Vance doesn’t seem to want to reform large foundations, so much as he wants to destroy them entirely), but in practical terms both groups have expressed their support for similar things, such as increased foundation payout rates. The question for the progressive critics of philanthropy is whether they should view this in terms of realpolitik and see it as an opportunity to work with Vance and others to push through reforms; or whether they should suspend their critiques (in the short-term at least), to avoid lending further weight to populist attacks that might damage philanthropy as a whole?

The threat to the long-term health of philanthropy doesn’t just come from government, however: arguably it comes just as much from philanthropists themselves at this point – particularly wealthy donors, whose actions (and inaction) may play a big part in shaping future public attitudes to philanthropy as a whole. There are suggestions, for instance, that Trump’s second term will bring with it a new age of conspicuous, unapologetic wealth – in which wealthy people may feel less need to acknowledge inequality or to profess a sense of responsibility to do anything about it. At the same time, the high proportion of billionaires who have been appointed by Trump to key roles within his administration will probably breed further cynicism about the influence of wealth on US politics. (Quite rightly so, and whilst that isn’t directly to do with philanthropy – since in this case these people are exerting influence through overt participation in politics – it will inevitably affect perceptions of wealthy people, and thus perceptions of elite philanthropy).

It is also true that even among wealthy people who aren’t directly involved in the Trump administration, there are clear signs that many of them are doing things designed to please Donald Trump in the hope of currying favour and keeping themselves out of his firing line: whether that is Mark Zuckerberg abandoning third party fact-checking on Meta platforms, Jeff Bezos halting funding for the Science Based Targets Initiative, or Google announcing it is scrapping its DEI programs. You might argue this is just pragmatics, and that it makes sense to adapt to changing political winds, but to many these look like prime examples of what the historian Timothy Snyder calls “obeying in advance”. As he warns in his book On Tyranny:

“Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these people think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.”

If wealthy philanthropists are seen to have made life easier for Donald Trump by obeying in advance, and are thus complicit in his attacks on philanthropy and nonprofits, then I suspect history – and indeed current civil society – will not judge them very kindly. If, on the other hand, they step up and use their resources to defend civil society against attacks, they can play an important part in defending a vital component of democracy, whilst also reaffirm the fact that philanthropy should be seen as a part of civil society, not something separate to it.

There will almost certainly be further challenges for civil society as a result of the Trump administration’s policies and Executive Orders, on top of those we already know about. CSOs will undoubtedly fight back – as, indeed, they are already doing through launching legal challenges and mobilising support. I am certain that behind some of this work are resources that have been provided by individual donors or foundations, but a whole lot more will be needed. Any support given so far has not been given particularly openly either. The question is, will funders remain circumspect for fear of bringing the ire of the administration down upon themselves, or will at least some of them be willing to come out of the woodwork and position themselves openly against Trump’s attacks on civil society? I really hope that it will be the latter, but it is far from clear yet which way all of this will go.