Rhodri Davies highlights a few thoughts prompted by the recent New Yorker magazine profile of philanthropist Leah Hunt-Hendrix.

17th August 2023

Recently, I read one of the most interesting articles on philanthropy I have come across for a while: a profile of philanthropist Leah Hunt-Hendrix in New Yorker magazine. The piece touches on many fascinating issues: including the relationship between where wealth has come from and the legitimacy of trying to do good through giving it away, the thorny dynamics that can occur within wealthy families when different members hold opposing world views, and the challenges of funding social movements through philanthropy. It sparked lots of thoughts for me (and judging from the response when I shared the article on LinkedIn, the same was true for others!) so I thought I would just take the opportunity to highlight a couple of those here.

The opening paragraph of the New Yorker article does really well in capturing the fundamental conundrum faced by those inheriting wealth that they feel to be somehow tainted. Is it better to wash your hands of the whole thing, by refusing to accept the money, or giving it away wholesale to someone else; or should you try to put that money to good use through philanthropy in a way that does something to address the harms done in creating the wealth?

Let’s say you were born into a legacy that is, you have come to believe, ruining the world. What can you do? You could be paralyzed with guilt. You could run away from your legacy, turn inward, cultivate your garden. If you have a lot of money, you could give it away a bit at a time—enough to assuage your conscience, and your annual tax burden, but not enough to hamper your life style—and only to causes (libraries, museums, one or both political parties) that would not make anyone close to you too uncomfortable. Or you could just give it all away—to a blind trust, to the first person you pass on the sidewalk—which would be admirable: a grand gesture of renunciation in exchange for moral purity. But, if you believe that the world is being ruined by structural causes, you will have done little to challenge those structures.

This resonated particularly strongly for me as I have recently been doing interviews with next gen philanthropists as part of the research for a book I’m working on, and one of the things I have definitely noticed with a number of them is precisely this sense of grappling with how to acknowledge concerns about structural inequality, injustice and problematic sources of wealth, without letting it prevent them from doing anything at all.

In the case of Leah Hunt-Hendrix, she seems to have combined a practical desire to do something with her wealth with a deep engagement with the fundamental questions it raises (up to and including studying philosophy and doing a PhD, which I have got a LOT of time for as an approach!) This has led her to a focus on trying to support grassroots organisations and social movements, and to do so in a way that avoids as many of the challenges that this often brings as possible (i.e. “movement capture”, where funders – even when well-intentioned – skew the focus of social movements they are funding; or “taming”, where funders soften the harder edges of grantees and try to steer them away from confrontational tactics). Hunt-Hendrix has identified the notion of solidarity as being core to the model of philanthropy she is trying to follow: indeed, one of the main organisations she helped to found is called the Solidaire Network.

This is really intriguing to me, as (in the UK, at least) the ‘philanthropic tradition’ and the ‘mutual aid/self help tradition’ are often identified as separate and divergent strands of the history of civil society, so to see an elite philanthropist try to bring these strands back together in a meaningful way is absolutely fascinating. I was excited to learn via this article that Hunt-Hendrix even has a co-authored book coming out next year which traces the history of the idea of solidarity and its influence (which I for one will 1000% be reading as soon as it comes out!)

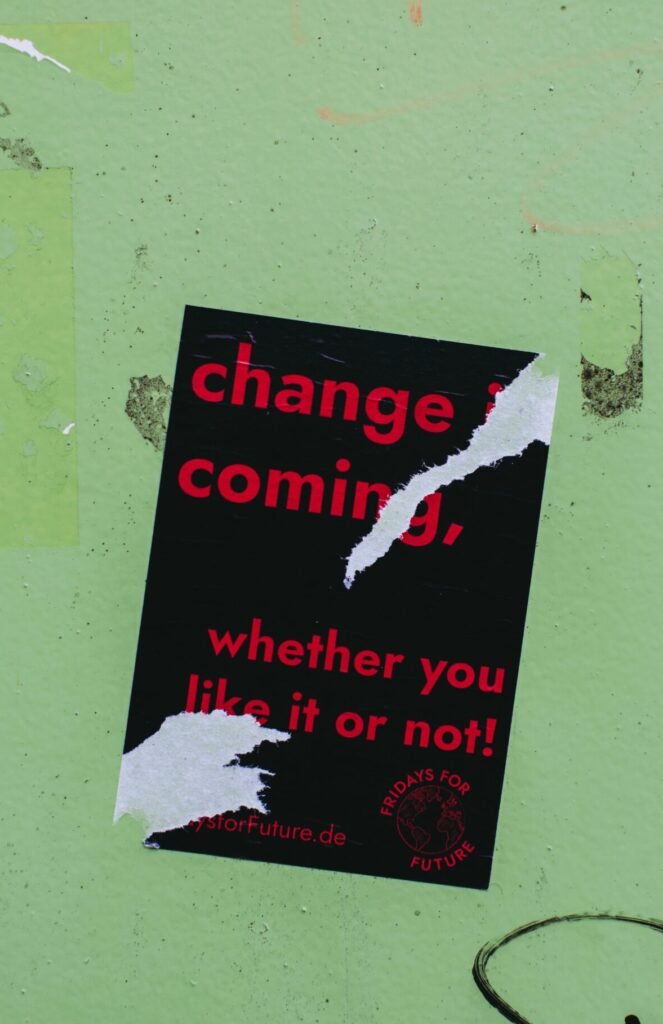

The New Yorker profile is certainly a sympathetic one, but stops short of being entirely hagiographic. The main grit in the oyster comes when the author questions whether Hunt-Hendrix’s desire to engage civilly with other members of her family who don’t share her views on climate issues had led her to be less forceful than she might have been. The family dynamics obviously bring an added dimension here, but the underlying question of whether it is more effective to take an incrementalist approach of working with the world as it is and seeking gradual change, or to take a more idealist approach which demands radical change and rejects compromise, is one that faces pretty much all donor and funders who are trying to address big systemic challenges like the climate crisis, inequality or racial injustice. This is definitely one of those questions that I haven’t made up my own mind on either, as I can go pretty hard in either direction on any given day (depending on how I am feeling about the world…)

One thing that doesn’t really come through in the article, but which is worth noting, is that whilst Hunt-Hendrix’s story is fascinating, and she is certainly unusual in the extent to which she is trying to shape an approach to philanthropy focused on justice, and designed (in part, at least) to atone for the injustices that gave rise to her wealth, there are at least some precedents that we can find. For one thing, her own mother (Helen LaKelly Hunt) is a pretty notable philanthropist in her own right, with a strong focus on issues of women’s rights. (She helped found both the New York Women’s Foundation and the Dallas Women’s Foundation and is President of the Sister Fund). She may not have been as vocal in disavowing the source of the family’s wealth (which in her case was her own father, H. L. Hunt), but she clearly did a lot to put that money to good use through philanthropy; in the same way that her daughter is now doing.

There is also at least some broader historical precedent for the scions of family dynasties to engage in radical philanthropy, up to and including approaches that attack the very nature of their own wealth. The one that came to mind for me when reading the article was Charles Garland (perhaps in part thanks to the mention of Megan Ming Francis’s excellent work questioning the history of the foundation he set up as an example of the dangers of “movement capture”). Garland became famous (or, in some people’s eyes, infamous) in the early 1920s, when he turned down a $1m inheritance from his father – a Wall Street banker. In her 1996 book, “The American Fund for Public Service: Charles Garland and Radical Philanthropy, 1922-1941”, Gloria Samson details Garland’s explanation of why he refused the money:

“The reporter asked the handsome young man, Charles Garland, why he had recently rejected a million-dollar inheritance. As he had informed the executor of his father’s estate, Garland now earnestly told the reporter his reason for refusing the money now due him in 1920. “It is not mine. I never did anything to earn it.” He refused to take money from “a system which starves thousands while hundreds are stuffed,” a system “which leaves a sick. woman helpless and offers its services to a healthy man.” It is such a system, he said, that “offers me a million dollars.” He wanted no part of it.”

Samson also notes that a number of prominent progressives of the time took issue with Garland’s decision, and urged him to accept the money and put it to good use instead:

“Upton Sinclair also urged Garland to accept the money. Writing from Pasadena, Sinclair scolded Garland, whom he had never met, for his rigidity and his excessive purity about money, quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson’s dictum that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds.” Never in the history of the radical movement “has anybody had a million dollars or a tenth part of that,” he wrote. Urging Garland to take the money and do good with it, he suggested specific organizations and individuals who would agree with Garland’s dislike of “the system” and would benefit enormously by his largesse.”

Garland did eventually heed this advice, and used the inheritance to set up the American Fund for Public Service (often known as the Garland Fund) – a limited life foundation that made a series of fairly radical grants to progressive causes (although many of them not radical enough in Garland’s own view).

Those like Leah Hunt-Hendrix, who find themselves faced with inheriting money that they find problematic, have to make a similar calculation today to the one Charles Garland made a century ago: is it better to turn down the money, and thereby keep yourself clean (but have no opportunity to influence how that money is used); or should you take the money in the knowledge of the ethical issues it raises, and try to do as much good with it as you can?

There are also some more recent historical parallels. I’ve got a second-hand copy of a fascinating 1992 book titled “We Gave Away A Fortune” which recounts the stories of a number of people who have used wealth (in many cases inherited wealth) to pursue highly progressive aims of social and environmental justice. This includes George Pillsbury (one of the heirs of the Pillsbury baking fortune, of “doughboy” fame), who founded the radical Haymarket People’s Fund – often cited as one of the pioneers of participatory grantmaking. It also includes Chuck Collins, an heir to the Oscar Meyer hot dog fortune, who also went on to co-author his own interesting book “Robin Hood Was Right”, which offers practical advice for donors on how to give in support of social change. (And yes, before you ask, I do have a copy of that one too…)

I should be clear that pointing out that there might be relevant historical precedents and parallels is not intended to diminish what Leah Hunt-Hendrix (or any other donor like her) is doing now. If anything, it makes it more interesting to me to think that such donors are not total anomalies, but rather part of a wider tradition of radical philanthropy. Of course, we should be clear that this kind of giving makes up only a tiny fraction of the overall landscape of philanthropy. But perhaps in coming years, as concerns about climate and inequality become ever more acute, we will see more of it emerge; and the inspiration and template provided by people like Leah Hunt-Hendrix will be a crucial part of making that happen.