16th September 2022

Yvon Chouinard’s decision to hand ownership of outdoor fashion company Patagonia to two newly-created nonprofit entities has made headlines around the world. We explore the precedents for his approach and what they might tell us about the questions we should be asking.

It was revealed in an article in the New York Times this week that Yvon Chouinard, founder of outdoor fashion manufacturer Patagonia, is giving away ownership of the company to two newly-created philanthropic entities focussed on addressing the climate crisis. This generated a huge surge of interest – not just in my Twitter timeline (which I realise may not be entirely representative of the public as a whole) but also in the wider media. And unusually for a story about philanthropy, pretty much all of the reaction has been positive (or, at least, it has so far…)

Patagonia has a long history of foregrounding social purpose: it has donated 1% of its sales to environmental causes since 1985 and it was one of the first companies to register as a B Corp when that designation became available. So this announcement has not exactly come out of the blue. However, the scale and nature of it has still raised many eyebrows, with the journalist who broke the story even calling it “a move with no precedent in the business world”.

I joined the ranks of people somewhat breathlessly tweeting about the news myself, declaring it “a pretty amazing precedent”. (I will admit that I was running a bath for my kids at the time whilst skim reading the NY Times article on my phone, so I can’t claim to have dug deeply into the details at that point). Quite a few people subsequently replied to question (in the nicest possible way, it must be said) whether what Patagonia are doing is in fact genuinely “unprecedented” and suggesting examples from elsewhere around the world that might provide evidence to the contrary.

This got me thinking: how do Patagonia’s plans fit into the history and wider global context of philanthropic entities taking ownership of for-profit companies? And even if what they are doing is not entirely unprecedented, what is noteworthy or interesting about it?

Foundations owning companies: global context and history

The first thing to say is that this is definitely not the first time someone has thought of creating a nonprofit trust or foundation in order to hand shares in a company over to it.

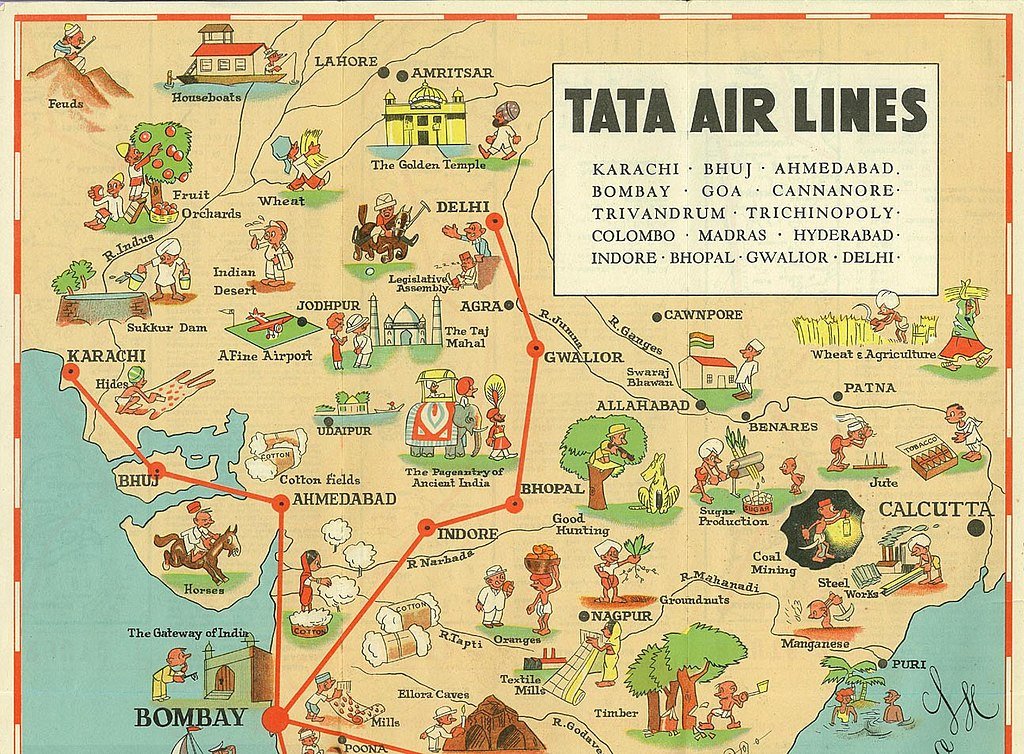

In fact there are far more examples around the globe of companies that are wholly or partly owned by foundations than you might think. This is particularly true in continental Europe, where the list of companies majority-owned by nonprofit entities includes big names such as Ikea, Heineken, Carlsberg, Robert Bosch, Bertelsmann and Rolex; as well as a significant number of banks in countries such as Italy and Denmark. But there are also examples from elsewhere in the world: India’s Tata Group of companies, for instance, is controlled by a holding company (Tata Sons Limited) which is itself around two thirds owned by a number of charitable trusts (with the largest shares being held by the Sir Ratan Tata Trust and the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust).

The foundation ownership model has a range of benefits for those involved (when done well, of course). It offers a way of enshrining a company’s social purpose, and thereby mitigating fears that it might be diluted or undermined by future takeovers or changes in stock ownership. It also offers a way for family-owned companies to manage the potentially thorny transition of ownership between generations. Foundation ownership often brings tax benefits too, since assets handed over to a non-profit entity are likely to be exempt from estate taxes and may even be eligible to be offset against income tax in some cases. (Although for many ultra-wealthy people this may not be such a big issue, as their wealth tends not to come in the form of income).

Critics often argue that foundation ownership results in a company becoming less profitable, since incentives for driving growth and turnover are reduced if the company is only able to pay out a smaller amount to shareholders. However, research has found that this is not actually the case, and that foundation-owned companies (broadly speaking) perform as well as those with more traditional shareholder structures. They do appear to grow more slowly; but on the flipside they also appear to last longer, have better staff retention and take on less debt.

Foundation ownership is far less common in the UK than in mainland Europe, though there are a few outliers. Some of these have historic roots, such as Scotland’s Robertson Trust, which has held the majority of shares in whisky manufacturer Edrington ever since the three Robertson sisters decided to give their holding in the family company away to a newly formed charitable trust in 1961. The Trust receives dividends from its holding in Edrington, which owns whisky brands including The Famous Grouse, The Macallan and Highland Park (so presumably feel free to drink those in good conscience; though obviously also in moderation…) There used to be lots of similar examples, some of which are detailed by Ben Whitaker in his book The Foundations (which is a wonderful look at the foundation world circa 1974, and remains one of the best books on philanthropy full stop IMHO). Whitaker lists, among others, the Wolfson Foundation (majority shareholder in Great Universal Stores), the Rank Foundation (Rank Plc), The Gannochy Trust (Bell’s Whisky) and The Grove Charity Management Trust (George Wimpey construction). However none of these, to my knowledge, have a majority shareholder role today (and indeed, in some cases the companies in question no longer even exist).

If you are looking for a more recent example one can be found in the form of North East England-based manufacturing firm Ebac, which was handed over to a charitable trust (The Ebac Foundation) by its owner John Elliott in 2012. The move, according to Elliott himself, was partly driven by a desire to ensure some money made its way to good causes, but also by a desire to ensure that the company remains in the North East and that its profits are reinvested into making manufacturing sustainable in the region. (Which, to me, comes across as an intriguing blurring of the lines between economic rationale and social purpose).

In the US, foundation ownership of companies is pretty much non-existent – primarily because there is a specific law limiting the amount of stock that a private foundation can hold in a single company to 20% of the total. But this is no accident. The reason this law exists is that at one time it was commonplace for foundations to own companies – indeed Ben Whitaker claims that by 1964 “the investments of half the fifty largest foundations – including at least nine of the twelve which are biggest of all – were overwhelmingly dominated by one donor stock”.

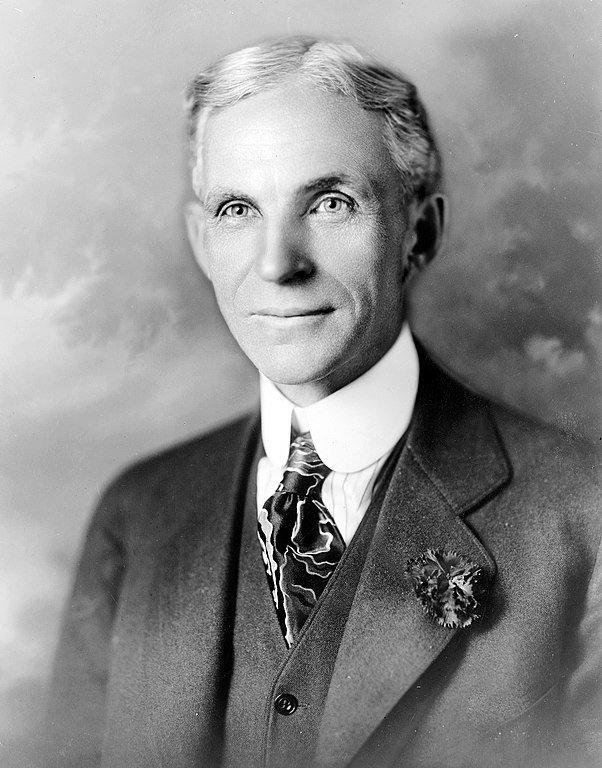

As Eric John Abrahamson argues in a great article for HistPhil, the trend for businessmen to hand over large quantities of their shareholdings to a foundation was kick-started by Henry Ford in 1936, when he changed his will to stipulate that 95% of the shares in the Ford Motor Company held by he and his son, Edsel, would be donated to the newly-created Ford Foundation on their deaths (which followed in the 1940s). As Abrahamson puts it:

“In the process, Ford let go of one of the greatest fortunes created in the history of the nation, but he saved his heirs an estimated $321 million in inheritance taxes.”

And it doesn’t seem as though Ford’s motivations were primarily philanthropic either, since:

“For Ford, the idea of creating a private foundation was not attractive. Generally, he believed charity promoted dependence. Socially, the capital generated from profits provided more benefits, including more jobs, when it was invested in entrepreneurial activity. Ford also thought that endowments and foundations tended to be slow-moving and conservative, benefitting insiders and employees more than society. But Ford was even more opposed to selling his company.”

A suspicion that many other foundation-corporate relationships were similarly driven more by self interest than altruism, and that the donors were often finding ways to ensure that money ostensibly given over to the foundation instead found its way back to them and their families in various forms of private benefit, gave rise to growing criticism. In 1950 President Harry S Truman said in a message to Congress that “the exemption accorded charitable trust funds [had become]… a cloak for speculative business ventures”, and in the same year the House of Representatives Ways and Means Committees was even more explicit, arguing that “frequently families owning or controlling large businesses set up private trusts or foundation to keep control of the business in the family after death,” and proposing that “no charitable deduction be allowed to a contributor… if the contributor and related parties control the trust or foundation to which the contribution is made and also control the business corporation whose stock is contributed.” (Quote taken from this 1999 paper by Thomas Troyer).

These proposals were not adopted immediately, but the baton was picked up in the 1960s by the US Congressman Wright Patman: a populist Democrat (and a pro-segregationist signatory to the “Southern Manifesto”) who became something of a scourge of the foundation sector. Patman’s dislike for foundations allegedly stemmed (according to Ben Whitaker, at least) from the fact that, as a child, his family’s grocery store had been taken over by Hartford A & P Stores, which was owned by the Hartford Foundation. Whatever the reason, Patman went on to lead something of a one-man campaign against philanthropic foundations. This saw many high-profile philanthropoids dragged in for Congressional hearings and eventually led to a series of new laws within the Tax Reform Act of 1969.

This Act is a hugely important landmark. Indeed some would argue that, by introducing for the first time a distinction between private foundations and operating charities, it created the US nonprofit sector as it exists today. However the most pertinent thing for our current purposes is that the Tax Reform Act brought in new rules governing the activities of foundations. This included a requirement that 5% of the value of a foundation’s endowment must be paid out for charitable purposes every year (a rule that still leads to much debate), as well as the restriction on the amount of a single company’s shares that a nonprofit can hold (20%, as mentioned above).

This law remains in force to this day, though I learned in the course of discussing this story on Twitter with people far more knowledgeable than me that the situation may have changed thanks to a new law introduced as part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, known as the Newman’s Own Exemption. This had been lobbied for by the Newman’s Own Foundation (which owns 100% of the Newman’s Own food brand following the death of actor and founder Paul Newman in 2008), on the basis that they felt unfairly penalised by the 20% restriction. From what I understand, this new law sets a high bar in terms of eligibility so it is unlikely that many existing foundation/corporate relationships would meet the criteria. However, it has reopened the possibility of 100% foundation ownership of a private company in the US for the first time in many years, so perhaps we will see more foundation-owned companies in the US in coming years.

And that brings us back to Patagonia. It may be that the fascination with this story partly reflects the fact that the rich history of foundation ownership of companies in the US has been somewhat forgotten, so to many commentators – or at least those who don’t spend their days obsessively poring through the history of philanthropy – this does all seem new and unprecedented. (However, as we shall see in a moment, the new entity that has been created to receive the vast majority of the company’s shares is not in fact a foundation – so most of what I have just said may be entirely irrelevant…)

But even if what Patagonia is doing is not entirely without precedent, are there elements of it that are genuinely new? And what questions should we be asking?

What is distinctive and interesting about the Patagonia example?

The main new nonprofit entity isn’t a foundation or a charity

Central to Patagonia’s plans is the new entity being created to take over control of the vast majority of the company, known as the Holdfast Collective. We don’t know much about this entity yet apart from the name, but the one thing we do know is that it is not a private foundation or a charity – rather it is a different kind of nonprofit entity, known by its super-catchy US tax code designation of “501(c)(4)”. To my mind this is one of the most interesting things about the Patagonia story, and the one that raises the most questions.

Why, for instance, have Yvon Chouinard and his family chosen to use a 501(c)(4) structure? And who is going to be in control of the new entity? One answer to the first question may be that it is a way of getting round the 20% ownership restriction discussed above. (Although, as we saw, the Newman’s Own exemption has already opened the door for private foundations to take larger stakes in private companies so we can’t assume this is the reason). Another explanation for the choice might be that 501(c)(4) organisations have more latitude to engage in political campaigning than traditional charitable organisations (which fall under the separate 501(c)(3) designation, and are therefore subject to restrictions on their ability to get involved in politics), and given that the focus of the Holdfast Collective is to address climate issues, the Chouinards and their advisers might have felt that the ability to get involved in politics was vital.

If one was a cynic, one could also assume less noble reasons for choosing a 501(c)(4) over a private foundation: for instance, in addition to being outside the rules limiting share ownership in companies, 501(c)(4)s are also not subject to the minimum annual payout requirements or to the same safeguards against self-dealing (i.e. using ostensibly philanthropic money for private gain). I don’t really see any reason to assume the worst in this case, particularly given that what Yvon Chouinard is doing is consistent with a long track record of social purpose activities by Patagonia. However, the longer we go without getting more details of the exact nature of the Holdfast Collective and how it will work, the more inevitable it will become that people start to raise these kinds of queries.

Split of voting/non-voting shares

Another interesting thing about the way Patagonia have chosen to structure this new arrangement is that although the Holdfast Collective will own 98% of the ordinary shares in the company, it won’t hold any of the voting shares. All of these will instead go to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, which will be controlled by the Chouinard family. This is different to some (though by no means all) other examples of corporate ownership by foundations, where the foundation is the majority shareholder and also has voting rights.

Again, until the Chouinards themselves clarify their thinking it is not entirely clear why this approach was taken. Perhaps they felt it was better to separate the Holdfast Collective as much as possible from decision-making about Patagonia? (And maybe this suggests that they envisage the new 501(c)(4) being more independent that we might have supposed?) It is perhaps worth noting, however, that one historical precedent for the approach they are taking would seem to be Henry and Edsel Ford, who gifted 95% of the stock in the Ford Motor Company to the Ford Foundation but retained all of the voting shares under the ownership of a trust owned by the family. And as we have seen, given the criticism this eventually led to it may not be a precedent one would particularly want to be associated with…

Donor motivation

We have been preoccupied so far with relatively technical questions of structure and governance, but it is also worth looking at what Yvon Chouinard has said about what motivated him (and his family) to make such a big philanthropic commitment. It has been widely reported that one of the big prompts was seeing himself included in a list of billionaires in Forbes magazine, and that this “really, really pissed me off because I don’t have $1 billion in the bank. I don’t drive Lexuses”. At a time when a growing number of donors (particularly next generation ones) seem to be increasingly uneasy about the disconnect between philanthropy and widening wealth inequality, perhaps this is a story we will hear more often: awareness of one’s own wealth triggering significant commitments to philanthropy as a way of trying to divest wealth.

Climate focus

Another aspect of the Patagonia story worth noting is that the focus of the new nonprofit entity is addressing the climate crisis. This is unsurprising given Patagonia’s past record of supporting environmental causes. However, given that less than 2% of charitable contributions worldwide currently go towards towards climate issues, it is still significant. And whilst Patagonia is clearly not going to solve the climate crisis on its own, what it is doing may act as a spur to other companies and philanthropic funders to do more.

Is this the acceptable face of dark money?

There is a final question we should ask (to ensure a bit of grit in the oyster): is the transfer of wealth to a new organisation that intends to engage in political campaigning something we should be applauding, or is it merely another example of the anti-democratic nature of big money philanthropy?

If, like me, the Chouinard’s focus on climate issues and their seemingly liberal worldview accords with your own preferences, then it is easy to get carried away being positive about this whole thing. But how is this fundamentally different from an example from the other side of the political spectrum – like, for instance, that of billionaire Barre Seid, who recently hit the news thanks to his enormous $1.6 billion donation to a new right-wing political advocacy group – except in that I happen to agree with this one?

This is where people often go wrong when it comes to addressing the question of how much freedom we should afford to philanthropists to advance their own views about what would make for a better society: they are inclined to be tolerant of those whose political views match their own, whilst being far more likely to be critical of those whose views they disagree with. As David Callaghan puts it in his 2017 book The Givers:

“When donors hold views we detest, we tend to see them as unfairly tilting policy debates with their money. Yet when we like their causes, we often view them as heroically stepping forward to level the playing field against powerful special interests or backward public majorities”

But if we really want to get to grips with the whole question of elite philanthropy’s role in a democracy, what we should be doing is thinking of the least palatable example of currently allowable philanthropy that we can come up with and asking whether we are willing to accept that as the cost of plurality and philanthropic freedom.

Given this, if I think that funding from a conservative billionaire for a new 501(c)(4) right wing political advocacy group is an example of problematic “dark money”, but I think that funding from a progressive billionaire like Yvon Chouinard for a similarly-structured organisation focussed on climate issues is a powerful example of philanthropic activism, am I just being a hypocrite? Or is there some qualitative difference here? It may be, for instance, that the Holdfast Collective is able to take some moral high ground on the basis of being more transparent (and thus, presumably, less “dark”) but the jury will remain out on that until we know far more about the new entity and how it will operate.

Where does all of that leave us?

Despite going into critical mode throughout this article, I broadly think that what Patagonia and Yvon Chouinard are doing is a good thing (though the claims that it is “unprecedented” might be a bit overblown, as we have seen). There are definitely still questions that need answering about the exact nature of the new entities that will take ownership of the company and who will control them. Some people might also have valid concerns about whether this all sits comfortably within a democracy. I must admit that I am more sanguine on that front in this instance, because the urgency of the need to address climate issues trumps many other considerations as far as I am concerned (though I recognise that this very much reflects my own views and that not everyone will agree with me). It will certainly be interesting to see what impact this has on other privately-owned companies and whether any follow suit in adopting a model of nonprofit ownership.