To mark the publication of Fozia Irfan’s report Transformative Philanthropy: A Manual for Social Change, we take a look at the history of philanthropy aimed at social justice in the UK.

7th February 2024

At the recent launch event for Fozia Irfan’s excellent new report Transformative Philanthropy: A Manual for Social Change (which I am absolutely delighted that we have also been able to help out with in a small way by hosting on this website), I was asked to say a bit about the historical context for philanthropy and social justice in the UK. Never one to let content go to waste, I thought I would turn this into an article too, so that anyone who wants to read it in conjunction with the report can.

The first thing you notice when asked to say something about the history of philanthropy and social justice is that the two have definitely not always been seen as natural bedfellows. In fact, they have sometimes been characterised as pulling in totally different directions. In order to understand why it is necessarily to delve far back into the roots of modern philanthropy, where we can identify the development of two distinct views of the nature and role of giving. The first of these views leads to an understanding of philanthropy as something that isn’t necessarily about furthering justice (and arguably might even get in the way of it sometimes); whereas the second is explicitly centred on the idea that philanthropy should aim to be a tool for delivering justice, and that we should shape our approaches accordingly. Historically speaking this latter notion of philanthropy – as something more radical and change-focussed – has perhaps tended to get overshadowed (at least in recent times); but in the context of thinking about how we can make philanthropy more justice-focussed today, it is important to realise that it has always been there and that there is a rich history we can draw upon.

If we take things back all the way to the medieval period, we find a situation in which the unequal distribution of wealth and rights was seen as something that wasn’t really up for question: it just was – a state of affairs fixed by God’s design. Which is not to say that the rich were simply given a free pass to hoard their wealth, as it was often argued (e.g. by Thomas Aquinas) that the rich were merely stewards of their wealth in this life (rather than “owners”), and that as such, even if they were allowed to have more than others, they also had responsibilities to use that wealth to support those with less through almsgiving and other forms of charity. But unlike later notions of philanthropy (of the sort we shall consider shortly), the aim of almsgiving was merely to meet the immediate needs of the poor within the existing structure of society. There was no sense of there being any aim of trying to change that fundamental structure. Indeed, it was generally seen as a good thing that there were so many poor people, as this meant that there was ample opportunity for wealthy people to demonstrate the virtues of mercy and charity.

The Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries brought massive changes in how we viewed the nature of property, and a shift away from the idea that its distribution was pre-determined by God. This thinking went in two key directions. On the one hand, there were people like John Locke, Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf, who argued that there were “natural rights” to property, which are prior to any man-made laws and are grounded in an individual’s right to claim ownership over that part of the world they have “carved out of the state of nature”. On this view, your property belongs to you because you’ve earned it, and it is a matter of choice as to whether you give any of it away to help others. Furthermore, the reason that other people don’t have property is taken to be that they aren’t trying hard enough, so we get a punitive and judgmental view of poverty that centres on the idea that some people are “deserving” whilst others are “undeserving”. The primary task of philanthropists then becomes to give in a suitably “discriminating” way that ensures the deserving get support whilst the undeserving definitely don’t. And this was very much the view of philanthropy that came to dominate the Victorian era, when concerns about the “evils of indiscriminate charity” were incredibly widespread. It is also an idea that has had a long-lasting legacy because it informed the thinking of many of the mega-donors of the early 20th century (Carnegie, Rockefeller etc), whose approach to giving set the template for a lot of what followed.

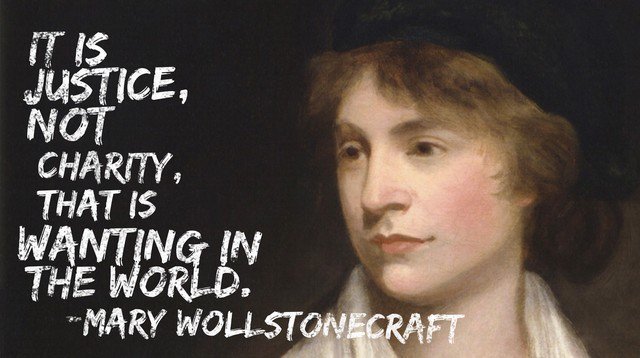

However, there was another way of thinking about wealth, poverty and charity that emerged during the Enlightenment and took things in a different direction. People like Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Immanuel Kant and Thomas Paine all argued that the unequal distribution of wealth is not a reflection of some sort of natural justice, but rather of flawed societal structures – and the only way of addressing this is through radical reform. Often this was taken as the basis for an argument against charity. Hence Wollstonecraft’s stark statement that “it is justice, not charity that is wanting in this world”, or Paine’s argument that “it is not charity, but a right; it is not bounty, but justice, that I am pleading for”. The alternative to flawed charity put forward by many of these thinkers was usually some form of redistribution through taxation (bear in mind, of course, that there was no income tax before 1799 and that it wasn’t introduced fully until 1843, so these writers were arguing for something that didn’t really exist at that point).

Despite the arguments that charity is an inadequate tool for delivering justice, there are plenty of examples of philanthropists who have tried use their giving not just to address the symptoms of society’s problems within existing structures, but to do something to change those very structures in order to make society fairer and more equitable. It is worth clarifying that this isn’t always about total reform of capitalism or the way wealth works – arguably that is a difficult, if not impossible ask, for philanthropy, since it is in many ways a reflection of inequality (on the presumption that it requires there to be “haves” and “have-nots”) and therefore may not be the best tool to address wealth inequality at a fundamental level. However, there are certainly philanthropists who have put a focus on other aspects of justice and rights at the core of what they did.

Even before people were using the word “philanthropy” in its modern sense, the London merchant Thomas Firmin was taking a partly justice-focussed approach in his giving. Firmin started off by addressing the symptoms of problems in the classic way; and was in fact so good at it that he developed a reputation among his peers which led to other rich men seeking him out to help them with their giving. Over time, however, Firmin shifted towards trying to address the more fundamental underlying causes of various social issues, rather than just their symptoms. For instance, he started off trying to help people caught in debtors’ prisons by giving them money to pay their bail, but over time branched out into challenging corruption among jailers and even taking some to court. Similarly, as well as being a successful merchant, he set up various businesses “for the employment of the poor” which were deliberately loss-making ventures that would pay workers (especially women) fair wages and give them good working conditions (with the loss of profit seen as a form of “thrifty philanthropy”). His aim was to demonstrate the value of the approach successfully enough to get government to take it on, but unfortunately he was quite a long way ahead of his time on that front.

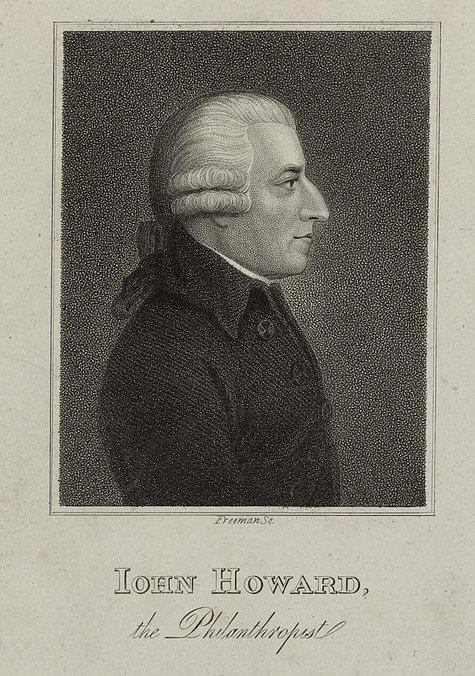

It is worth noting (as a fun fact to share at parties, perhaps) that when the word “philanthropy” did re-emerge into modern English usage in the late 17th and early 18th century, it was actually associated far more with notions of social campaigning and reform (and therefore justice), than it was with simply giving money. So the first person to be known as a philanthropist in the modern sense was the prison reformer John Howard. Who did give some money, to be sure, but it definitely wasn’t the defining characteristic of what he did or why he became so famous. That was far more to do with his single-minded focus on gathering data about conditions in prisons across Europe and using the information to lobby for reform at the highest levels (work that led to him being claimed on his death in 1790 as “the consummate philanthropist” and “God-like Howard”, and meant that even a century later the Times was using him as a yardstick against which to measure late 19th century philanthropists unfavourably). Similarly, other notable early modern “philanthropists” were people like anti-slavery campaigners William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, or the prison campaigner Elizabeth Fry; none of whom were defined by the size of their largesse, but rather by their tireless efforts to push for justice and reform.

Over the course of the C19th, “philanthropy” did come to be associated more with monetary donations and the giving of wealthy people, and the reformist, campaigning notion of philanthropy that was central to the 18th century gradually became overshadowed. It never totally disappeared though, and we can still find plenty of examples of philanthropy being used as a tool for agitation and reform. The wonderfully-named “Society for Superseding the Necessity for Climbing Boys”, for instance, was founded in 1803 to try to find a solution to concerns about the use of chimney sweeps. They offered a prize for the invention of a machine that would do away with the need to send children up chimneys, and also lobbied parliament to change the law.

There were also individual figures who were successful in business, and therefore accumulated wealth, but still wanted to use their philanthropy to push for fundamental reform. The Welsh textile manufacturer Robert Owen, for instance, developed a model of “Utopian Socialism” at his mills in New Lanark in Scotland – focussing on workers rights, childcare and free education – which was admired by many who visited, including senior politicians and royals (although sadly not emulated by most of them…) Quaker philanthropists, like George Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree, also clearly held wider concerns about justice to be important. They were aware that when it came to trying to do good in the world, how wealth was created was just as important as how it was given away, so they brought in new innovations in terms of working conditions and built model towns for their employees to live in (such as Bournville and New Earswick). In addition, they used ownership of newspapers and involvement in politics to campaign for change on issues such as pacifism, and also used new social research methods to highlight the scale of poverty – information that could then be used as the basis for a case for further state involvement in welfare provision. They were also keenly aware of the potential tension between philanthropy and justice. Indeed, Rowntree wrote in 1865 that:

“charity as ordinarily practised, the charity of endowment, the charity of emotion, the charity which takes the place of justice, creates much of the misery it relieves, but does not relieve all the misery it creates.”

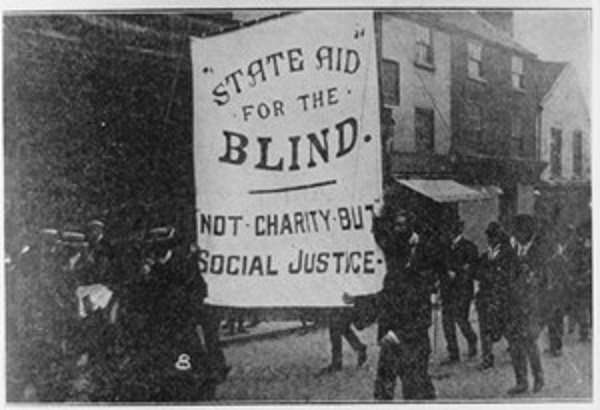

As the 19th century turned into the 20th century, the social justice aspects of philanthropy became more apparent once again, with philanthropic support at various levels playing a vital role in campaigns such as the fight for universal suffrage. A key part of this role was providing resources in the early stages of the suffrage movement’s development, when it was crucial to develop public awareness and support and to build the machinery for grassroots organising. Philanthropy has played a similar role in other examples of campaigns for social change, such as the fight for LGBTQ+ rights or the right to access to land: providing vital funding at an early stage so that issues can be taken on a journey from the margins to the mainstream, which eventually leads to political or social reform.

The other thing that happened in the first half of the 20th century which is highly relevant to the question of philanthropy’s relationship to justice is the emergence of the welfare state. In large part this came about because the Victorian era had seen a ‘grand experiment’ of trying to meet the needs of society through philanthropic means, but this had failed. It had become apparent by the early 20th century that philanthropy wasn’t up to the task of providing universal welfare: both because it simply wasn’t large enough in scale, and because its essentially voluntary nature made it ill-suited to ensuring an equitable and just distribution of resources. It therefore became increasingly apparent that state involvement was necessary. The gradual introduction of state education in the late 1800s was followed by the introduction of state pensions in 1911, and an accelerating process of state acceptance of responsibility finally culminated in 1948 with the launch of the National Health Service (generally seen as the ‘birth of the Welfare State).

There were many who thought that the creation of the welfare state would spell the end of philanthropy, and in some cases they weren’t particularly sad about the idea. Health Secretary Aneurin Bevan, for instance, celebrated the fact that access to healthcare would no longer be based on a “patchwork of local paternalisms” because he thought it “repugnant to a civilised community for hospitals to have to rely upon private charity”. Of course, as we know now, the birth of the welfare state didn’t spell the end of philanthropy by any means. For one thing (much as William Beveridge had suggested would be the case in his 1948 book Voluntary Action), there were still gaps and failings in state provision; there were also new and changing needs that required adaptation and innovation (which the state was not always good at), as well as things the state was never going to provide so they would always require funding through philanthropic means.

One thing that did happen following the creation of the welfare state was that many philanthropy and voluntary organisations were forced to reconsider their role, and for some this meant rediscovering the spirit of radicalism and campaigning that had been there back at the birth of modern philanthropy. Thus in the 1960s and 1970s we have existing organisations taking more of a campaigning role, and also the formation of new justice-focussed campaigning orgs like Shelter, Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) and Amnesty International, which would further push the boundaries when it came to making charity a means of pushing for radical justice-based reform.

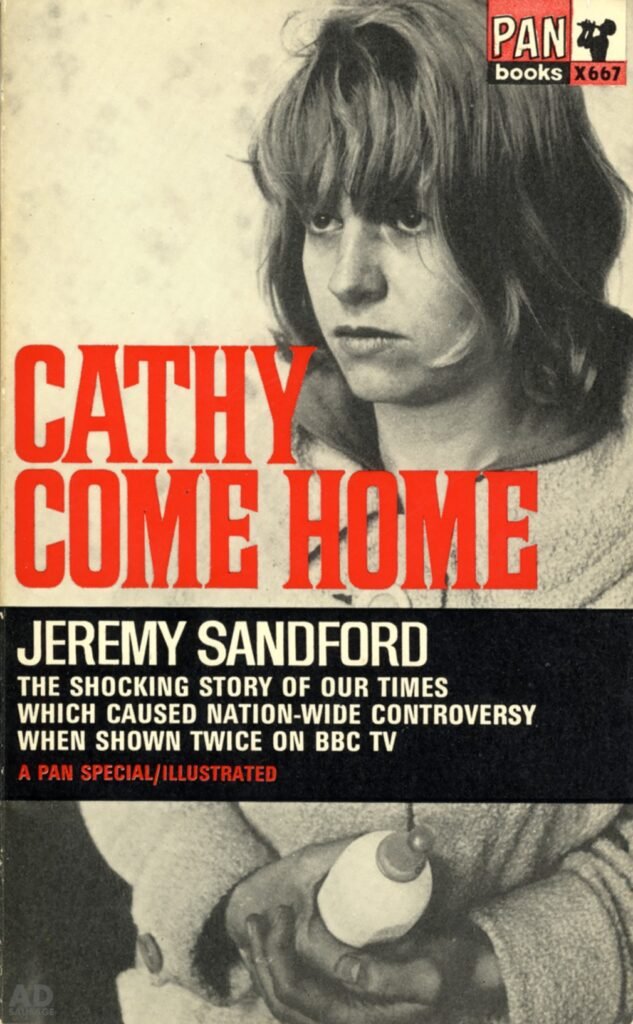

Evidence of the exact role that philanthropy played in supporting this new spirit of justice focused campaigning is hard to come by. (In fact, as an aside, one of the main things I have been reminded of whilst pulling this article together is quite how maddeningly hard it is to find sources on philanthropy at a sectoral level in the latter half of the 20th century!) We do know that some of these campaigning organisations enjoyed widespread public support from the outset, and were very successful in fundraising from the general public. The launch of Shelter in 1966, for instance, coincided with the screening of Ken Loach’s highly influential TV drama “Cathy Come Home”, which led to a huge upsurge of awareness and concern about homelessness as an issue, and many people looked to the newly-formed organisation as an outlet for their concerns. Other campaigning organisations, on the other hand, faced a constant struggle to raise funds from the public – either due to lack of awareness, or because the causes they were focussing on were not seen as sufficiently “appealing”. The level of support from institutional philanthropy (i.e. charitable foundations) and from big money donors is more difficult to determine, although we can identify individual examples. We know, for instance, that both Shelter and CPAG received money from the Baring Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust (although that of course, and perhaps tellingly, is not a charitable foundation…) We also know that the Albany Foundation was established by a group of donors (including some with significant wealth) as a vehicle to support the work of the Homosexual Law Reform Society and ensure that the decriminalisation of homosexuality recommended in the 1957 Wolfenden Report was taken forward. (NB: for more on this history, see this WPM article exploring lessons from the history of philanthropy & the fight for LGBT+ rights.) And there are also intriguing examples like that of the Abortion Law Reform Association, whose work in conducting research and polling was vital in securing a change in the law in 1967 to decriminalise abortion, and who were largely funded by a single US foundation up to that point (The Hopkins Charitable and Donations Funds of Santa Barbara).

The involvement of a US foundation in the last example above is perhaps telling, as it is certainly a fact that it is easier to determine a clear history of distinct social justice or social change philanthropy in the foundation sector in the US than it is here in the UK. Which is not to suggest that this kind of philanthropy has ever been mainstream in the US either – it certainly hasn’t, and has only ever been a marginal part of the overall philanthropy landscape at best – but it has been there. From early pioneers like the American Fund for Public Service (aka the Garland Fund), the Rosenwald Fund, The Stern Fund and the Field Foundation, which supported racial equality, civil rights and economic justice, through to later inheritors of the social justice philanthropy mantle such as the New World Foundation, the Taconic Foundation, the Twentieth Century Foundation, and The Haymarket People’s Fund, there has been a distinct and coherent (if small) subsector of social justice philanthropic funders in the US for at least a hundred years. (You can read a bit more about this history and how it might be informing current philanthropy in this WPM article). The question here in the UK is whether our charitable trusts and foundations have been funding similarly radical work, but have just been less likely to self-define as social justice funders (thus making it harder to identify common threads)? Or do we have something to learn from the US when it comes to using philanthropy – and particularly foundations – as tools for genuinely radical efforts at reform?

What we can say with certainty is that the ideas of campaigning and advocacy have been important parts of the voluntary sector and philanthropy in the UK from the outset. They haven’t of course always been appreciated by everyone (especially not by those who happen to be in power, and thus the targets of criticism, at any given time!) And there have certainly been efforts to constrain the ability of voluntary organisations to speak out on issues that are deemed political. (For more on this history, check out this WPM article). At times the voluntary sector itself has perhaps taken its eye off the ball too, and been guilty of downplaying the importance of its campaigning and advocacy role in the pursuit of government contracts or insider influence. However in the last few years there has been renewed focus on the importance of civil society voice and the role it plays in speaking truth to power. In that context, it is vitally important that we once again ask what positive role philanthropy can play in supporting powerful and potentially radical efforts to push for a more just society. And, of course, how philanthropy itself might need to change to do that. So Fozia’s report couldn’t have come at a more crucial time, and I really do urge everyone to read it and think through what it means for them and their work.