How is philanthropy being affected by culture war narratives? And is it partly to blame for the whole problem?

A recurring motif in current media and political debate is the idea that as a society we are engaged in a “culture war”. In fact, just this week UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson doubled down on it in his speech to the Conservative Party conference, declaring that “it has become clear to me that this isn’t just a joke — they really do want to rewrite our national story… We really are at risk of a kind of know-nothing cancel culture, know-nothing iconoclasm.”

Depending on your point of view, the culture war can either be interpreted as a battle of the forces of progress and social justice against those who hark back to a rose-tinted (almost certainly mythical) past and have a vested interest in maintaining an unfair status quo; or it can be interpreted (as Johnson and others would have us believe) as a battle between defenders of traditional values and freedom of speech against the massed hordes of intolerant wokeness. Either way, this debate is very rarely edifying (especially when taking place on social media); as nuance and tolerant engagement with differing points of view more often than not get abandoned in favour of gladiatorial point-scoring and self-conscious attempts to signal membership of one “side” or other in the war.

But what does this mean for philanthropy and civil society? Should those of us working in these fields engage with culture war debates, or consciously stay out of them? Is this even possible, or will we inevitably end up being dragged in anyway or becoming collateral damage in wider battles being fought around us? Will the polarisation of discourse and debate undermine civil society’s voice, and thus limit its ability to seek change through advocacy and speaking truth to power? Does cultural polarisation within the world of philanthropy threaten to tear it apart? And is philanthropy itself at least partly to blame for the culture wars in the first place?

(Now, stylistically speaking, that really is quite a long list of rhetorical questions for a 3rd paragraph. But hopefully it does convey the sense that this is a complex topic that needs far more unpicking).

Is there a culture war, and should we care?

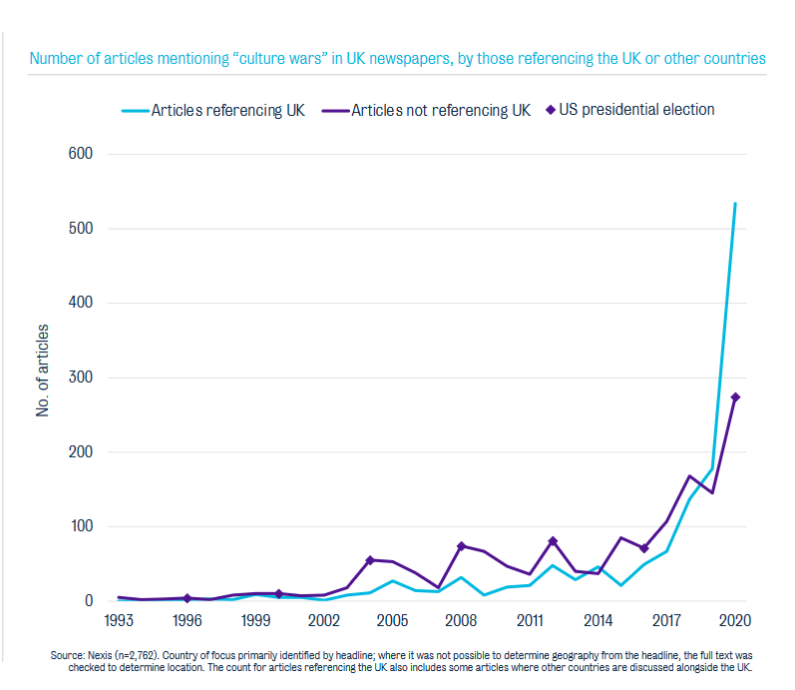

Before we get to any of those questions, however, the first thing we should do is sense-check whether there is really a problem here. The Policy Institute at King’s College London, for instance, which has done perhaps the most detailed analysis of this topic, found that whilst there has been a definite increase in media mentions of culture wars and related issues in recent years (in 2020 there were 534 UK newspaper articles focusing on the existence or nature of culture wars, up from just 21 in 2015), it is still far from clear that the public understands what they actually are, or believes that they matter even if they do (e.g. the UK public is as likely to think “being woke” is a compliment as they are to think it is an insult; and by far the most common response when asked to describe what sort of issues the term “culture wars” makes them think of is that it doesn’t make them think of any). The Policy Institute did find, however, that whilst the UK is not polarised in the way that the US is, there is definite potential for the country to slide in that direction — particularly given that there seem to be overt efforts from a number of directions to stoke culture war divisions. Part of the problem, as political commentator Matthew d’Ancona points out, is that “everything the government has on its to-do list is hard”; so faced with the challenges such as post-Brexit supply chain issues, the aftermath of the pandemic and following through on their “levelling up” agenda, it is sorely tempting for politicians instead to focus on putting out tweets and op-eds designed to amplify apparent cultural divisions and fill the headlines with a series of confected rows, because that is far easier.

This is something that the charity sector in the UK has certainly had experience of in recent years. Former Chair of the Charity Commission, Baroness Tina Stowell, for instance, was an early adopter of culture war narratives. From early in her tenure, a key centrepiece of her approach was to attack the charity sector (sometimes in person, but also in the form of columns in right-leaning newspapers) for being out of touch with ‘public opinion’ on issues that she argued had become political, and that as a result they risked damaging the trust of their supporters and the wider public. (It has to be said that the ‘public opinion’ in question was often backed up only by rather questionable polling results that tended to conflict with findings elsewhere).

More recently, now-former Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden doubled-down on culture war narratives in his dealings with the sector: picking fights with the National Trust over their work uncovering hidden histories of links of slavery at their properties, convening meetings of arts and culture organisations in order to threaten them about not being sufficiently cheerleading about Britain’s history of empire, and wading into an entirely overblown row about plans by the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust to make a slight amendment to their name. Those worried about the long-term damage this might do to relationships between the government and civil society may therefore have breathed a sigh of relief when Dowden was moved on in a recent reshuffle; however, this was short-lived as his replacement, Nadine Dorries, has her own long track record of stoking up culture war issues - a widely-quoted tweet of hers from 2017, for instance, proclaimed that:

If this kind of oppositional approach also becomes the norm in interactions between civil society and government it is clearly going to be a lot harder to get meaningful engagement or compromise, which will make campaigning and advocacy far more difficult. There may also be knock-on effects on public opinion and levels of trust: although it seems as though the public are not that bought into culture war narratives thus far, the steady drip-drip of media stories and comments from politicians implying that the charity sector has been captured by a fifth column of liberal elite social justice warriors who want to use and abuse beloved national institutions to fit their own radical woke agenda hardly seems likely to bolster widespread public trust in the value of an independent civil society. Even if most of the time the vast majority of the public has no interest in this kind of nonsense, the danger is that it sets a problematic and negative background narrative — so that when stories about charities do come to wider public attention, it is in the context of the average punter having a vague sense that charities are all somehow ‘a bit suspect’. And that should be a cause for concern for all of us.

Undermining civil society voice

Attacks on the campaigning role of civil society are, of course, not new. The understandable (if somewhat depressing) gap between the willingness to recognise the theoretical importance of organisations that are able to speak out on issues and hold those in power to account, and the willingness in practice to respect and protect the rights and freedoms that make this possible — particularly when you are the one being held to account — means that politicians have often taken issue with civil society advocacy and voice. This has been a particular leitmotif within Conservative party rhetoric over recent years; where a clear view of charity has emerged that implies (or occasionally just states) a distinction between small volunteer-run organisations that deliver services to address the symptoms of issues in society (which are Good) and large, professionalised organisations that engage in campaigning to influence social change designed to address the causes of those problems (which is Bad). Similar sentiments can also be detected in some of the the pronouncements of the Charity Commission, which is perhaps even more problematic given its role as a supposedly independent regulator for charities. It should be stressed, however, that the Commission has subsequently gone out of its way to clarify that it does believe campaigning by charities to be valid and important (as Commission CEO Helen Stephenson outlined in this admirably unequivocal blog). Although even had this clarification not been forthcoming, it is far from a new thing for the leadership of the Charity Commission to take a slightly lukewarm view of campaigning: in 1979, for example, outgoing Chief Commissioner Terence FitzGerald wrote in the Sunday Telegraph that “the role of charity is to bind up the wounds of society. This is what they get their fiscal privileges for. To build a new society is for someone else.”

Although attacks on the involvement of charities in “politics” are not new, the emergence of culture war narratives has had the effect of turbo-charging them, and providing a range of new tools to those who (for whatever reason) want to undermine the legitimacy of civil society campaigning. If a charity campaigns or expresses a view on a social issue, for instance, it is no longer necessary for potential opponents to counter any research, evidence or experience the charity may have used to make their case: instead, you can simply attempt to delegitimize the charity by implying (or just outright claiming) that they are driven by a divisive “woke” agenda. Alternatively, you can redefine the issue that the charity is speaking out on as one that is inherently “political” and argue that by taking a side on it, the charity is being “divisive”, “ignoring the views of its members” or “straying into politics”, as Tina Stowell did in her last speech as Charity Commission chair.

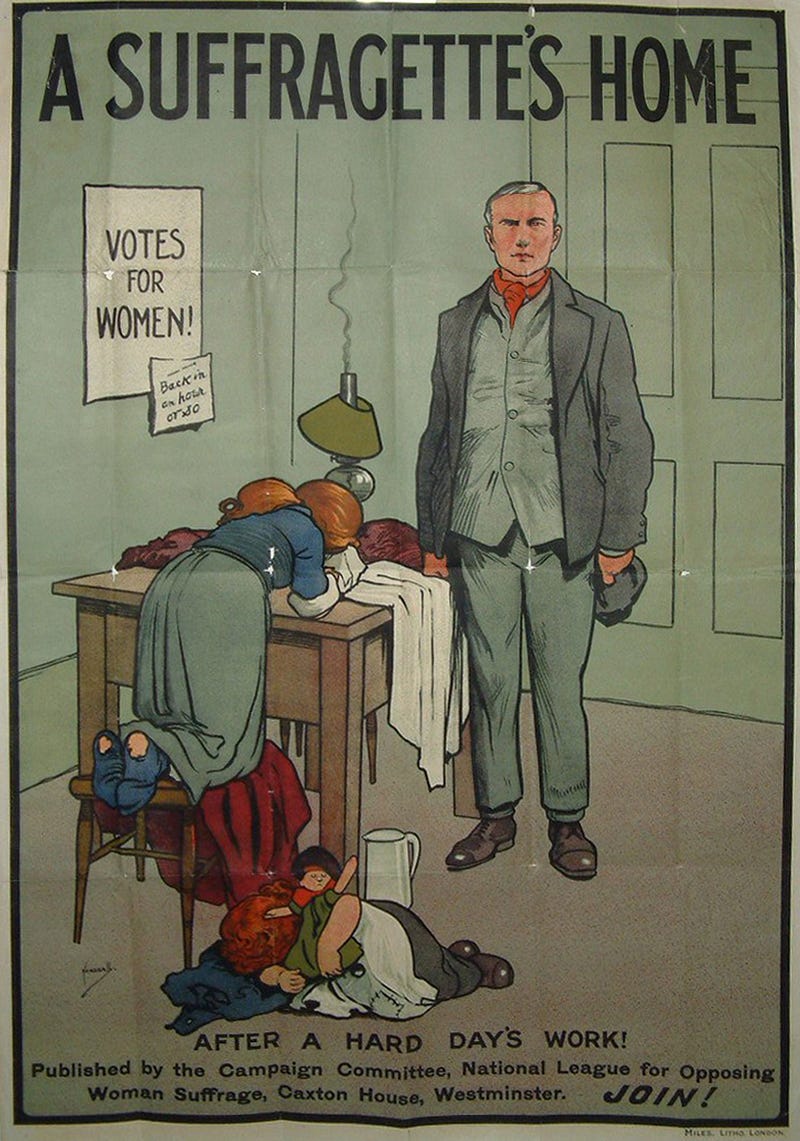

As an aside, I find this ‘both sides’ line of argument pretty baffling, as it seems to imply that charities need to maintain balance when it comes to any issue that might be deemed contentious or divisive. Yet this runs counter to pretty much the entire history of how civil society has actually successfully fought for milestones in social progress. How would the fight for the abolition of slavery, for instance, have worked if all the organisations working on it had been forced to acknowledge the potential upsides of slavery at all times? Likewise, if the Suffragettes and others had had to ensure they considered the views of those who objected to votes for women in all their activities, might this not have undermined their case somewhat? Of course, in all these examples there have been civil society organisations on both sides of the argument (e.g. it is worth reading up on the history of the anti-suffrage movement and the many prominent philanthropic women who took part in it), but this should be unsurprising given that civil society is a reflection of the plurality of views within society as a whole. What makes no sense at all is to suggest that every individual organisation needs to reflect all of the potential dimensions of public opinion on any given issue.

Currently charities are allowed by law to engage in “political activities” in furtherance of their purpose, but they are not allowed to have purposes that are overtly political. It is worth noting that this principle is based on far shakier historical foundations than might be supposed (as outlined in this Twitter thread) and that it has subsequently been subjected to significant scrutiny and calls for reform- both in other jurisdictions that have followed the lead of UK charity law, such as Australia (as detailed in this fascinating 2011 paper on the Aid/Watch vs Federal Commissioner of Taxation case), and in the UK itself (e.g. the Institute for Economic Affairs recently attempted to square the circle of limits on the ability of think tanks to engage in political issues by proposing a new charitable purpose of “advancing debate for the public benefit.”) For now, however, the rule prohibiting political purposes remains and most charities are able to navigate it fairly well (with the occasional edge case continuing to test the law). The additional challenge that the culture war narrative brings, though, is that it enables the definition of the political sphere to be extended to pretty much any issue on which one can claim there is division, so it becomes far less clear for organisations when they might be accused of “straying into politics”. The danger is that this has a chilling effect, as charities refrain from speaking out on issues for fear of falling foul of the rules and their ability to hold those in power to account becomes diminished. But then again, maybe that is the point.

Polarisation within philanthropy

So far we have focused on the impact of culture wars on civil society organisations, but what about the impact on philanthropy? Well, in one obvious sense the former is very much linked to the latter — because supporting civil society organisations is the primary way in which most philanthropists and funders try to pursue their goals, so anything that undermines the legitimacy of CSOs or their ability to drive change is also detrimental to philanthropy. However, there may also be other ways in which philanthropy is more directly affected by culture war narratives.

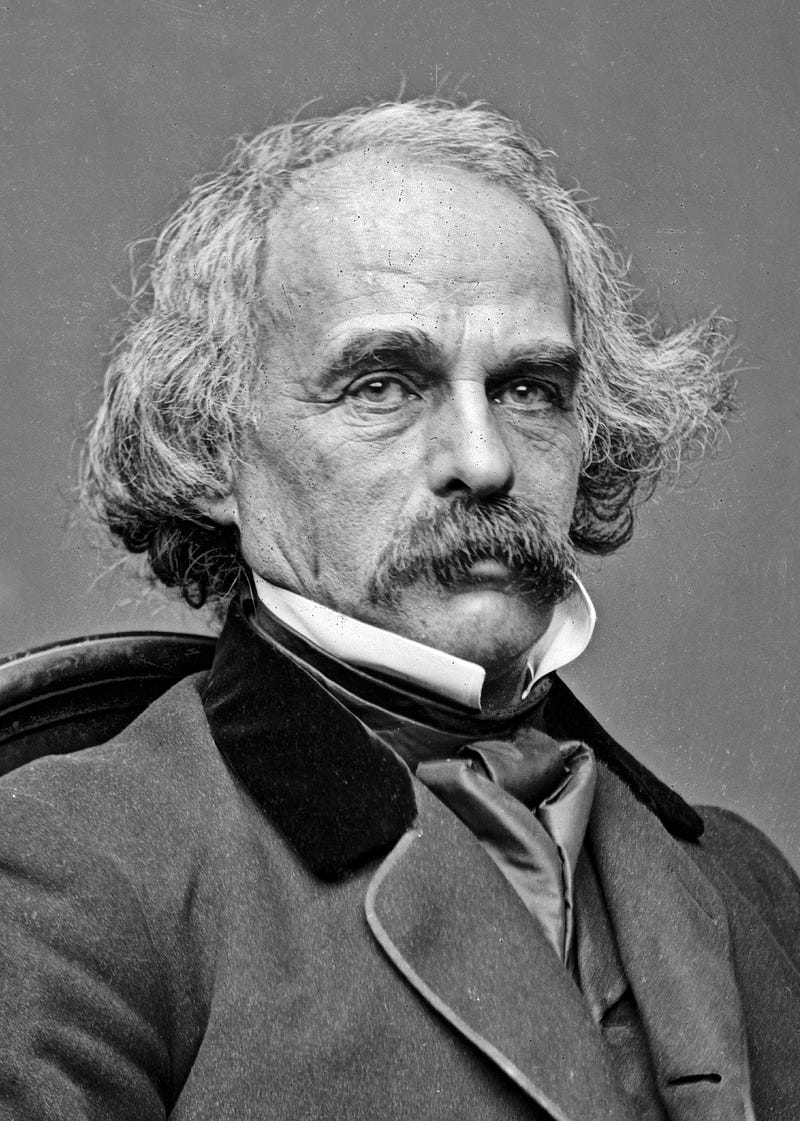

For one thing, it may add to the risk of absolutism in philanthropy — where people or organisations come to believe that their views or approach are the “right” ones to the exclusion of any others — because culture war divisions are designed to make it far easier to dismiss those who hold different views. Of course this is not a new problem — in his 1843 short story “The Procession of Life”, for instance, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote that:

“When a good man has long devoted himself to a particular kind of beneficence — to one species of reform — he is apt to become narrowed into the limits of the path wherein he treads, and to fancy that there is no other good to be done on earth but that self-same good to which he has put his hand, and in the very mode that best suits his own conceptions. All else is worthless. His scheme must be wrought out by the united strength of the whole world’s stock of love, or the world is no longer worthy of a position in the universe.”

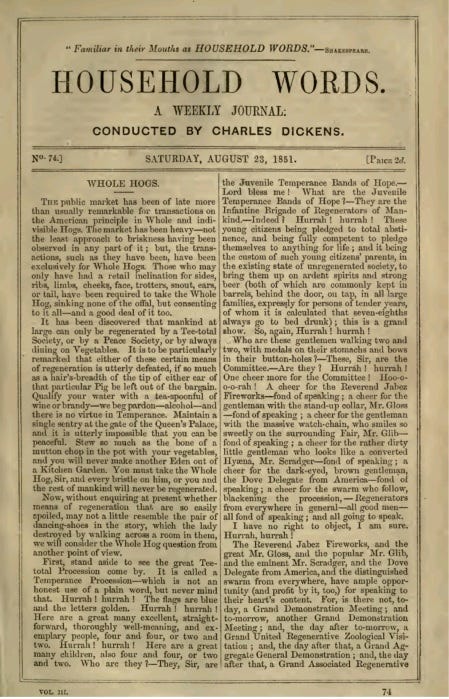

Similarly in an 1851 article entitled Whole Hogs, Charles Dickens poked fun at the pomposity and absolutism of social reformers, writing that:

“It has been discovered that mankind at large can only be regenerated by a Teetotal Society, or by a Peace Society, or by always dining on Vegetables. It is to be particularly remarked that either of these certain means of regeneration is utterly defeated, if so much as a hair’s-breadth of the tip of the ear of that particular Pig be left out of the bargain.”

Despite these known dangers, however, philanthropy (at its best) still has a long history of bringing together those from different walks of life and differing viewpoints to address shared concerns. We shouldn’t be naive and assume this has always been easy: in fact more often than not it has brought to light problematic power dynamics and the often unavoidable tension between donor and recipient. It has also required compromise: both on the part of CSOs and activists who may have to accept the need to soften their approaches or dilute their aims, and also on the part of donors and funders who may have to accept the need to give up control or to accept risks that they might not otherwise be comfortable with. Compromise may not be ideal from everyone’s point of view. In fact it may be inevitable that, as Larry David said, “a good compromise is when both parties are dissatisfied”. But those of even a vaguely pragmatic bent are likely to acknowledge that compromise is more often than not a necessary part of doing philanthropy. The challenge, then, will come if culture war narratives make this kind of compromise less possible because people become more absolutist or tribal.

Will the culture wars result in less philanthropy?

As well as making it harder to do philanthropy well, is there also a danger that polarisation could result in less giving in the first place? Empathy is an important driver of charitable behaviour, and is determined by the extent to which we are able to “put ourselves in someone else’s shoes”. Some argue that this already makes empathy a flawed basis for altruistic behaviour because it limits our scope and wrongly leads us to focus on those most identifiably “like us”. If culture war narratives take hold and lead to more entrenched divisions and the “othering” of those who are perceived to be outside our “tribe”, then it is not hard to see a situation in which our capacity for empathy (and thus our drive to give) is reduced even further.

Are there also risks that culture wars might lead to more conscious decisions on the part of potential donors not to give because they are worried about potential criticism? I have certainly had conversations with journalists, researchers and donors who want to know whether what they perceive to be the rise of “cancel culture” (especially at universities and cultural institutions) is having a negative impact on donations from wealthy individuals who are reluctant to put themselves at risk of getting cancelled. I’m not sure there is any real evidence for this as a widespread phenomenon at the moment, and it feels like most of the arguments I have seen suggesting that it is rely on suitably cherry-picked examples that imply a vague sense of something going on. But as with so many other aspects of culture wars, if you repeat something enough times it might well become true — because people respond to what they are told is a trend and in doing so the trend becomes real. So whilst those seeking to encourage and promote philanthropy might well need to guard against the risks of donors getting cancelled, it is even more likely that they will need to guard against donors preemptively cancelling themselves in the face of the perceived threat of being cancelled by others.

The challenge of contextualising philanthropy

One of the potential causes of donor nerviness may be awareness of the growing number of institutions and organisations that are reckoning with problematic elements of their own histories (most often links to slavery and other exploitative practices), which has resulted in a number of high profile incidents in which philanthropists of the past have been disavowed. Some of these long-dead donors have had their names taken off institutions (e.g. Cass Business School at City University in London, originally named after merchant and slave owner Sir John Cass, is now Bayes Business School), some have had their statues taken down (e.g. slave owner Thomas Picton, whose effigy is still encased in a wooden box in Cardiff’s City Hall pending a decision on what to do with it) and others have found their likenesses cast to the bottom of Bristol Harbour (as famously happened to the long-controversial statue of merchant and slave trader Edward Colston). The Policy Institute at Kings College London found that issues of Empire and slavery, particularly in reference to the removal of statues, were at the centre of the highest number of media stories about culture wars in 2020, so it is unsurprising that people are aware of them. Quite why some philanthropists find these stories so worrying is less clear, but perhaps the best guess is that it is due to a combination of broad concern about the wider divisions that arguments over statues represent and a more direct concern that growing scrutiny of historical sources of wealth will spill over into scrutiny of current sources of wealth and result in philanthropists like them being vilified.

This is one of those areas, like many others that get caught up in culture war narratives, where lack of nuance becomes a real problem. Placing philanthropy in the wider context of how wealth has been generated is, in my opinion, absolutely critical — as without doing so the legitimacy of philanthropy is always in question. That is why it is important that we grapple with the complex ethical issues raised by “tainted donations” — whether those come from historical donors with links to slavery or from problematic modern donors like the Sackler family or disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein — and that we do so in a way that does not involve simply jumping to the conclusion that “all philanthropy is bad”. Similarly , when it comes to historically tainted donations we need to have a much more sophisticated understanding of what history actually tells us. In the case of Edward Colston, for instance, the story of his statue is less about what he was like as an actual philanthropist (FYI not especially pleasant or praiseworthy by all accounts) and more about how a mythos was developed around him and his generosity that suited the needs of competing groups of merchants in Bristol more that 150 years later — as they were the ones who actually put up the statue. (If you want to read more about the history of the Colston statue and how it fits into the wider debate over tainted donations, I wrote a piece all about it back when I was at CAF).

How best to deal with statues and names commemorating figures from the past whose philanthropic deeds are now seen to be outweighed by the wider harms they may have caused remains a hot topic of debate; and one that raises many questions for organisations who owe some or all of their existence to historical gifts that are tainted in some way. Is it enough merely to acknowledge the issue? Should we remove elements of commemoration (or does this risk being tokenistic)? Is it better at this point to keep the “bad” money and “do good” with it, or do we need to be more proactive about making reparations of some kind (and if so, how)? These are not easy questions to answer, but they are important questions nonetheless. Likewise, the question of what donors and recipients should do in response to concerns about modern sources of wealth and tainted donations is thorny but vital to address. If nuance-destroying culture war battles undermine efforts to do so, then this is a real problem for philanthropy as a whole.

Philanthropy in the culture wars: victim, saviour or perpetrator?

It may seem from what has been said so far that the main relevance of the rise of culture war narratives for philanthropy and civil society is the risk of being damaged or undermined (whether deliberately or unintentionally) by the polarisation of discourse and the politicisation of a growing number of issues. But is this too defeatist? Rather than seeing philanthropy and civil society as victims of culture wars, should we instead see them as a vital part of the solution? Many who have studied the culture war phenomenon clearly think so: the Policy Institute at King’s College London, for instance, make it one of their recommendations that “civil society needs to be supported in providing sites for real-world connections across divides: we know that real-life contact, in the right settings, reduces the sense of division”. As we mentioned above, philanthropy can definitely play an important role in providing space for people from different walks of life or different viewpoints to come together, or as a tool for brokering compromise.

It has long been noted, too, that philanthropic giving and voluntary action may have significant value in building social capital and fostering wider civic engagement: acting, in de Tocqueville’s words, as a “nursery of democracy”. However, we should not simply assume that all forms of philanthropy or voluntary association enhance civic life in this way. As many critics point out, there are certainly forms of both that seem far more likely to harm it. Should, for instance, my active participation in an anti-vax conspiracy group be seen as a good thing because I am getting out there, building connections and learning valuable tools of civic engagement? Or should it be seen as a bad thing because of the impact the group as a whole has on democracy and society? I’m pretty comfortable going for option “b” here. (There are many more fascinating historical examples of “uncivil civil society” that challenge the Tocquevillian notion of voluntary association as an inherent nursery of democracy in this forum from HistPhil).This is not meant to be a counsel of despair, though: I still believe that philanthropy and voluntary action can enhance civic engagement and thus strengthen democracy — we just can’t assume that they will, and need instead to take a more intentional approach to the methods and models we use in philanthropy in order to ensure that they have a positive impact overall.

If we are to make philanthropy part of the proposed solution to culture wars, it is important that we also acknowledge it has been part of the problem and recognise the role philanthropy has played in fomenting culture wars in the first place (and in sustaining them). It has been noted by many (and often, it has to be said, in slightly envious terms by Progressives) that conservative philanthropy in the US has proven highly successful over the last 40 years or so . As Sally Corrington outlines it in her chapter “Moving Public Policy to the Right: the Strategic Philanthropy of Conservative Foundations” (in Faber & McCarthy (ed) Foundations for Social Change):

“[T]he long-term investments that conservative foundations have made in building a “counter-establishment” of research, advocacy, media, legal, philanthropic and religious sector organizations have paid off handsomely… Their successes, on both a broad ideological and public policy level, are readily apparent.”

(More detail on the history of US conservative philanthropy for those who are interested can be found in another series of articles on HistPhil). Clearly one of the tactics of conservative funders has been to put in place the elements of the culture war we now find ourselves in (as detailed in this 2013 Guardian article). This may seem like a specifically American problem, but as we have seen although culture war narratives developed in the US they have very definitely been exported to the UK. And philanthropy is continuing to play a role in sustaining them — most notably through the work of right-wing think tanks and their networks of not-usually-very-transparent donors.

Where, then, does this leave us? Well, as is often the case with anything to do with philanthropy, once you start delving into the details you find that it is complicated. Culture war narratives certainly provide challenges in terms of undermining the legitimacy of civil society voice, causing polarisation within the nonprofit world itself, and making it harder to engage with debates in a nuanced way so that philanthropy can be put in the required wider context. But they may also provide opportunities for philanthropy to show its worth; by driving positive civic engagement, fostering civil debate in which a variety of viewpoints can be heard, and ensuring that there are spaces within civil society for people on different sides of issues to come together in productive and non-confrontational ways. However, we cannot escape the fact that philanthropic funding continues to supply the means for culture war narratives to be developed and disseminated; and if philanthropy is to be part of the solution as well as part of the problem, we need to find ways to address that.