This is the third and final part of an essay mini-series exploring the nature and role of philanthropic foundations. Here we consider some of the key themes that have emerged throughout the long history of critique and criticisms of foundations, and how these might inform our understanding of current debates.

14th November 2023

(Read part 1 HERE and part 2 HERE).

In parts I and II of this essay mini-series we explored what foundations are and took a whistle-stop tour through their history (it might not have felt it was that whistle-stop, but trust me – that was very much the short version!). Let’s turn now to what this tells us about the role of foundations in society and the arguments for and against them. I’m going to divide this up into a series of themes and look briefly at why they have been important historically and why many of them are still highly relevant to current debates about foundations.

Death, perpetuity & the dead hand

It should be clear from the historical outline we sketched earlier that foundations have always been closely linked with death. The endowment idea, wherever it has arisen, has been an attempt to cheat the inevitability of death, by allowing an individual to extent their will and personality into the future in the shape of a legal entity that carries out good works in their name. (For more on the relationship between death and foundations, I would recommend checking out this great paper by Tobias Jung and Kevin Orr). As we have seen, this function of foundations has always attracted criticism and controversy from those who feel that it allows the “dead hand of the donor” to exert undue influence over the living.

Efforts have been made at various times to address these concerns – in the early 20th century the Sears & Roebuck CEO Julius Rosenwald established his own foundation with a limited lifespan, making it clear that he was ‘opposed to gifts in perpetuity for any purpose’ because ‘whilst charity tends to do good, perpetual charities tend to do evil’. More recently, the duty free billionaire Chuck Feeney (who died recently) became famous for giving away almost all his fortune through his Atlantic Philanthropies foundation during his lifetime. There are also examples of perpetually-endowed foundations that have taken the decision to turn themselves into limited-life foundations and “spend down” over a set period (such as the Edward W Hazen foundation). But these examples are noteworthy precisely because they are very much the exception rather than the norm. The default is still for endowments to be established in perpetuity, and so questions about whether we need to counter the influence of the dead hand of the donor remain highly relevant when it comes to foundations.

The current debate tends to be framed in terms whether foundations should exist in perpetuity or be forced to spend down. Proponents of the former argue that one of the main strengths of the foundation form is that it enables a long term view when it comes to addressing issues, and that this is particularly valuable at a time when political and market cycles have become ever shorter. There is undoubtedly some truth in this, and if all foundations were to spend down in the next 10 years I suspect the short-term benefits would be outweighed by the challenges of having to deal with the remaining longer-term challenges without the help of foundations. Those who argue in favour of spending down, however, might argue that some of the issues we face today – in particular the climate crisis – are so urgent and existential that we need to deploy more resources now simply in order to ensure that we have a meaningful future. The arguments for long-term stability and patience, and those for short term urgency and action, both seem to have merits; so the question for foundations when it comes to their own existence and potential end is where to draw the appropriate line between now and forever.

Taxes

It is often said that the only two certainties in life are death and taxes. This is certainly true of foundations, since as well as allowing donors to avoid death, they have long played a role in enabling them to avoid taxes. And, as we have seen, this has brought criticism from those who feel as though the benefits of offering tax advantages to foundations are not outweighed by the loss of revenue that this means for the state. At times this criticism has become particularly acute, as in the US in the 1960s when the concerns over foundation corporate shareholdings and other abuses came to a head and resulted in the new measures in the 1969 Tax Act which reshaped the nonprofit sector.

The tax-advantaged nature of foundations is an important part of the backdrop to current debates and controversies too. When it comes to concerns about whether UK foundations are not paying out enough and should be subjected to a mandatory payout rate, for instance; or concerns that large sums of money in the US are being paid into Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) but not being given out again to nonprofits, one of the defensive arguments often made is that independent institutions or private individuals should be free to choose what to do with their own resources. But of course this ignores the fact that DAFs and foundations enjoy tax advantages, so in some sense they are subsidised by the state through the tax money that we all collectively contribute and therefore (the critics would certainly argue) we all have a stake in what they do, even if only indirectly.

There is then a choice about what to do: do we challenge the idea that foundations should enjoy tax advantages on the basis of their perceived failings to distribute enough money or be sufficiently transparent? (And if so, what is the potential cost of doing so?) Or do we have to accept the fundamental validity of giving tax breaks to foundations and their donors and just suck up the bad stuff? (And if we are taking this course, what actually is the justification for governmental tax breaks on philanthropy? That in itself is a whole other can of worms that would require and equally long article to unpick, so will have to wait for another time…) Or is it possible to navigate a course between these two options, in which we accept that there is some fundamental validity to the idea that foundations and their donors should receive tax breaks, but also argue the nature of these tax breaks is not determined by this basic justification and that it is therefore acceptable to design them with a view to shaping foundation practice in particular ways. Some might argue, for instance, that foundations should have to meet minimum transparency requirements in order to qualify for tax breaks; or that they should be able to show demonstrable levels of impact. Any such ideas would be complex to implement, and might well bring the risk of unintended consequences (and I strongly suspect they would meet fierce opposition from many existing foundations!), but if scrutiny of foundations continues to grow these kinds of reforming proposals will almost certainly become a bigger part of the debate.

Risk & Innovation

We touched briefly in the previous section on the question of how the tax-advantaged status of foundations is justified (before hastily skirting round it), but one feature common to many proposed justifications that is worth touching upon is the idea that foundations partly owe their legitimacy and their privileges to the role they play in being able to take risks and therefore drive innovation and “discovery” in society. This risk-taking role is often taken to be axiomatic: foundations have sometimes been described as “society’s risk capital”, and the Director of the Carnegie UK Trust declared when giving evidence to a government inquiry in 1952 that “it is the business of trusts to live dangerously”.

This raises some important questions: firstly, is it actually necessary for all foundation work to be “risk-taking” and “innovative”, or is it OK to fund at least some things that are tried and tested but just need resourcing? The argument sometimes made is that those kinds of activities could surely be financed by other means (e.g. government funding, charging for services etc), but this doesn’t seem to be necessarily true. There are many things that government can’t or won’t fund (particularly in this era of straitened public sector budgets), and which it is either not feasible or appropriate to charge for, and in this situation surely there is at least a pragmatic argument for accepting that it is OK for foundations to fund these activities (even if it is not theoretically ideal).

The second question we might ask is: even if we accept that foundations need to be risk-taking or innovative to some extent, what does this actually mean? We often equate “innovation” with “doing new stuff”, but there is also a case to be made that funding existing things to continue and grow, or funding work aimed at ensuring we don’t lose things we already have, is an equally important kind of risk taking. The third and final question we might then ask is: if we have a proper understanding of risk and innovation and believe they are a necessary part of foundation’s role, how many foundations are actually achieving this in practice? Historically, one can find many examples of foundations funding research that resulted in medical breakthroughs or scientific innovations, or of foundations supporting unpopular or marginalised causes and taking them on a journey from the ‘margins to the mainstream’ that resulted in genuine societal progress, but we need to be careful not to assume from these heroic examples that all foundations are therefore bold risk-taking pioneers willing to put themselves and their reputations on the line to push society forward. The concern that some critics express is that large parts of the foundation world are in fact quite risk-averse and small-“c” conservative – willing only to fund things that they feel are “safe bets”, so that their own self-image and reputation as grantmakers is maintained. If risk-taking and innovation are core parts of the justification for the legitimacy of foundations as a whole, then this is obviously a real problem.

Pluralism

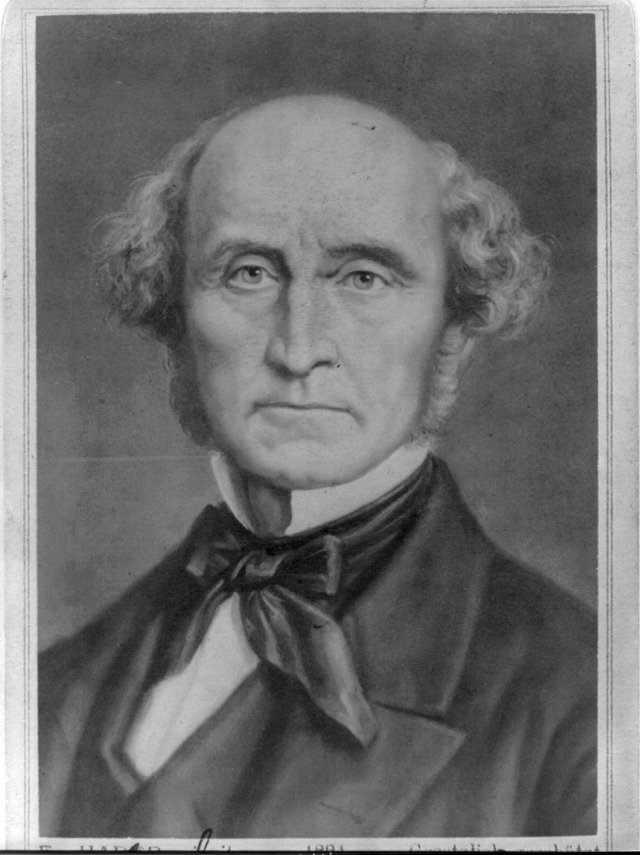

Another argument in favour of foundations, linked to the one above about risk and innovation, is that regardless of exactly what it is they fund, they bring value to society simply by funding lots of different stuff and thus encouraging pluralism of ideas and actions. In particular, it is argued, they can fund things that don’t enjoy popular support, or run counter to the status quo of a particular time, and thereby play an important role in overcoming the “tyranny of the majority” that can occur in a democracy, whereby minority interests and views are never able to find expression through the electoral system. The classic statement of this idea comes from John Stuart Mill, who argued in an 1869 essay on “Endowments” that:

“Endowments… [are] a precious safeguard for uncustomary modes of thought and practice, against the repression, sometimes amounting to suppression, to which they are even more exposed as society in other respects grows more civilised.”

In the same year, the social reformer Thomas Hare argued that:

“Endowments [are] an important element in the experimental branches of political and social science. No doubt the nation at large may take on itself the cost of such tentative efforts, but this involves taxation; and the assent of the majority to increased taxes could not be justly demanded by philanthropist or projectors, and certainly would not be obtained until their speculations had taken such a hold upon the public mind as no longer to require an exceptional support or propagation. The most important steps in human progress may be opposed to the prejudices, not only of the multitude, but even of the learned and leaders of thought in a particular epoch.”

The danger, of course, is that even if this kind of argument sells us on the value of pluralism, the reality might not live up to our theoretical ideals . For one thing, can we assume that everyone involved is acting in good faith? That seems dangerously naïve given that there are plenty of bad actors out there who would be willing to profess enthusiasm for the idea of plurality simply because they know that will serve their own interests better. For another thing, even if those involved are not acting in bad faith, we need to bear in mind that the majority of foundations represent those who have benefitted from the status quo, and are therefore going to be more inclined to protect it to some extent. Ben Whitaker put this concern very neatly in his 1974 book The Foundations:

“A convincing rationale for foundations requires more than the standard incantations regarding the virtues of pluralism and innovation… all good philanthropoids recite on arising and retiring. A conviction that the theoretical concept of independent foundations is a potentially beneficial one is not the same as believing that their present operation should not be drastically improved. Currently, their efforts are too often open to the criticism that they are principally used merely to lubricate the machinery of the status quo, for almost all the people who control foundations belong to segments of society whose privileges predispose them to be basically satisfied with its present structure – and indeed frequently have a vested interest in preventing any seriously radical reforms.”

In the past, many have argued that the value of pluralism that we get from allowing foundations to proliferate unencumbered is sufficiently great that we should be willing to accept the existence of some things that we find problematic or disagreeable as the necessary cost. The Rockefeller Foundation’s Warren Weaver, for instance argued in 1967 that:

“If we believe in democracy and in the right to express dissenting ideas, a small amount of pathology must be tolerated in order to maintain the health of the main social body, somewhat as protective antibodies are produced in the human body by injecting small amounts of material associated with disease. The edge of desirable experimentation must continuously be tested with vigour and variety, and can be located only by occasionally crossing it. We accept a small risk to make a large gain.”

More recently, however, the tide seems to have turned against the idea that pluralism is an inherent good in itself, with many now arguing that some things that donors or foundations do represent too high a price to pay, and should be delegitimised rather than accepted. An op-ed in the Chronicle of Philanthropy earlier this year sparked a furious debate in the US philanthropy sector and highlighted the fact that on this question there are currently deep divisions of opinion. (For a fascinating historical perspective on the pluralism debate in the US, check out this recent Urban Institute report by Ben Soskis).

Anti-Democratic

The flipside to the arguments in favour of foundations outlined above, on the grounds of innovation and pluralism, is that in both cases one of the main reasons foundations are well-placed to demonstrate these strengths is precisely because they are not really accountable to anyone. And that lack of accountability (together with a lack of transparency), critics argue, makes them profoundly anti-democratic, as they represent a means for those with wealth to bypass the machinery of electoral democracy and exert undue influence on public debate and public policy without being accountable to voters or to shareholders in the way that governments or companies are.

There is a sense in which this criticism is undeniably true: foundations are unavoidably anti-democratic if your understanding of what constitutes democracy extends only as far as the sphere of government and the electoral system. If, however, you are willing to allow a broader conception of democracy which includes various checks and balances on the power of the state – such as an independent judiciary, a free press and a healthy civil society – then foundations can be argued to be an important element of a democracy understood in this way. The challenge, of course, is that this is another one of those points at which a theoretical rationale might be far easier to accept than the reality of how it tends it play out in practice. In this case, the debate usually ends up being about particular examples of the influence of foundations or philanthropy that people find egregious because they come from the opposite side of an issue or the wider political spectrum. As David Callahan puts it in his 2017 book The Givers:

“When donors hold views we detest, we tend to see them as unfairly tilting policy debates with their money. Yet when we like their causes, we often view them as heroically stepping forward to level the playing field against powerful special interests or backward public majorities… These sort of a la carte reactions don’t make a lot of sense. Really, the question should be whether we think it’s okay overall for any philanthropists to have so much power to advance their own vision of a better society?”

When it comes to foundations and their role in a democracy, we therefore need to ask ourselves whether we feel it necessary to exclude certain approaches or points of view that we think are unacceptable, in the knowledge that others might well challenge approaches or points of view that we do agree with. And if so, where the lines are drawn (and who gets to draw them).

Lack of transparency

We have mentioned in passing a few times already that transparency (or lack thereof) has been a long-standing point of criticism for foundations. To give a sense of why, it is worth noting that best estimates suggest that only around 10 per cent of US private foundations even have a website. (I’m not sure what the equivalent figure would be in the UK or elsewhere, but I’m willing to bet it wouldn’t be significantly higher). Now, in some cases this will simply be a reflection of that fact that a foundation doesn’t have the infrastructure or staff to maintain a web presence (which is fair enough), whilst in other cases it might well reflect an explicit desire to remain anonymous or avoid scrutiny; either way, the net result is that the foundation world remains remarkably opaque. There are pockets of light emerging in this picture: the efforts of initiatives like 360 Giving in the UK or Glasspockets in the US to make foundations more open and transparent are certainly helping to improve things, but there is still a lot further to go.

Even as foundations take tentative steps to become more open, the overall situation might actually get worse if donors increasingly turn to other vehicles that are even less transparent. There has been a significant growth in the use of Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) in the US over the past few decades for instance (and some growth in the UK, although nowhere near as much). There is also a more recent trend for elite donors in the US (particularly those from a tech background) to use entirely non-charitable structures for their philanthropy, such as Limited Liability Companies (LLCs). A wide range of rationales is put forward for the use of both DAFs and LLCs, but it is undoubtedly the case that an important one is the fact that they are subject to even less stringent requirements in terms of transparency than the fairly minimal demands made of traditional foundations, and this is a real cause of concern for some critics. (For some recent commentary on the use of LLCs, check out this Alliance magazine article by Aaron Horvath and Micah McElroy).

Making giving “better”

For a large part of their history, as we have seen, foundations represented above all else an effort to project the values and wishes of a donor beyond their own lifetime. But since at least the late 19th and early 20th century, they have also represented something else: a desire to systematise, to formalise and to rationalise what was seen as a natural but unruly instinct towards generosity into something more “strategic” and “scientific” that could be harnessed in the service of grand ambitions to “improve the condition of mankind.” Victorian England had seen the emergence of the Charity Organisation Society (COS) movement, which aimed to combat what it saw as the “scourge of indiscriminate giving” and to educate people about the “correct” way to give in order to ensure that money did not make its way into the hands of the “undeserving poor”. The COS made many enemies through its combative and dogmatic approach, but it also proved to be highly influential on thinking about philanthropy – both in the UK and the US, where its ideas morphed into the doctrine of “scientific charity”, which became fundamental to the approach of many major philanthropists of the early 20th century (most notably Carnegie and Rockefeller), and as a result has come to exert a significant influence on how we think about foundations ever since.

Today there is an ongoing debate about whether foundations should adopt “trust-based” or “strategic” approaches to giving (and also, it should be said, plenty of debate about whether this is a false binary, and we should all stop talking about it…). Proponents of trust-based approaches argue that the paradigm of strategic giving is based on an inherently top-down conception where what is “strategic” is determined by the donor, and their will and worldview is then imposed on recipient organisations or communities who have little say in the matter. Instead, they argue, funders should see it as their role to empower grantees, by providing them with resources that do not come with restrictive conditions or onerous reporting requirements, but are unrestricted and based on long-term, trusting relationships. Proponents of strategic giving, meanwhile, argue that is the responsibility of donors, funders and advisers to ensure that philanthropic resources are used in a way that achieves maximum impact, and that this can only be done by retaining a high degree of control and involvement (and often by applying “business principles” or an “investment mindset”).

The strategic giving side of the argument has a clear lineage back to Carnegie and Rockefeller, and for a long time represented the dominant line of thinking within the world of foundations. More recently, however, there has been a resurgence of interest in trust-based models; one which seeks to position them not as a sentimental throwback to a unsophisticated pre-scientific approach to philanthropy, but rather as an effective approach to grantmaking that also addresses some of the challenger arising from the natural power imbalance when those in possession of resources interact with those who have need of them. Whether one side in this debate “wins out”, or whether we will find a suitable compromise between the two remains to be seen.

Power imbalance

One of the criticisms of strategic giving, as outlined above, is that it places too much power in the hands of the funder in relation to the recipient. To some extent, however, this is merely exacerbating an existing problem rather than creating a new one, since the very nature of philanthropy (at least when understood as a transfer of resources from ”haves” to “have-nots”) means that it results in asymmetrical power dynamics. Since foundations generally represent large accumulations of philanthropic assets, the power imbalances between them and their grantees can often be significant.

There have been plenty of examples of foundations throughout the 20th century and into the 21st that have been keenly aware of these challenges and have tried to overcome them in one way or another. In some cases that was driven by a founder who wanted to find ways of doing their philanthropy that allowed them to give away power as well as money. For example Charles Garland, whose radical views and distaste for capitalism at first saw him reject an inheritance of nearly $1 million dollars from his father (who had been a securities broker) in 1919, before various prominent progressive figures such as Upton Sinclair convinced him that he should accept the money and put it to good uses, which he did in the form of the American Fund for Public Service– a limited-life foundation which existed between 1921 and 1941. Garland himself did not want to make decisions about how the money was distributed, so he appointed a board of progressive experts and empowered them to distribute the money instead. There is also the example of Julius Rosenwald, whose second phase of philanthropy through his Rosenwald fund saw him give out hundreds of small, no-strings-attached grants to Black individuals (including artists, musicians, scientists and doctors), many of whom went on to be prominent cultural figures and in some cases leading lights of the early civil rights movement. Rosenwald’s daughter, Edith Rosenwald-Stern, adopted a similar approach to her own philanthropy and through her Stern Fund she supported many progressive and radical causes such as voter registration. Later in the 20th century, a group of social justice foundations came together as the Funding Exchange in 1979 (founded by, among others, George Pillsbury – an heir to the Pillsbury fortune (of “doughboy” fame)), and experimented with various approaches designed to democratise the process of philanthropy, such as participatory grantmaking (the Haymarket People’s Fund, which was a core member of the Funding Exchange, is often cited as an early pioneer of this kind of approach). And right now there are funders such as FRIDA/Young Feminist Fund or Borealis Philanthropy that are continuing to explore ways in which the foundation model can be adapted and refined to rebalance power in favour of the organisations and communities that might once have been seen merely as grateful recipients.

History shows, however, that overcoming the inherent power imbalances in philanthropy can be hard, even if the intent is there. Scholars like Megan Ming Francis and Claire Dunning have used historical examples to argue that even in the cases of the seemingly most progressive or radical funders, the structural and cultural realities of the foundation model mean that there is a risk of hidden strings being attached to apparently unrestricted funding, or a risk of “movement capture” occurring – where social movements or grassroots organisations are co-opted by funders who may (consciously or unconsciously) seek to shift their priorities or to discourage them from using certain tactics that are seen as too confrontational. At a time when new forms of technology-enabled social movement are playing an increasingly prominent role in driving action on social issues, it is more important than ever that we are aware of the potential challenges that may come from power imbalances in the relationships between foundations and social movements.

Commemoration and social status

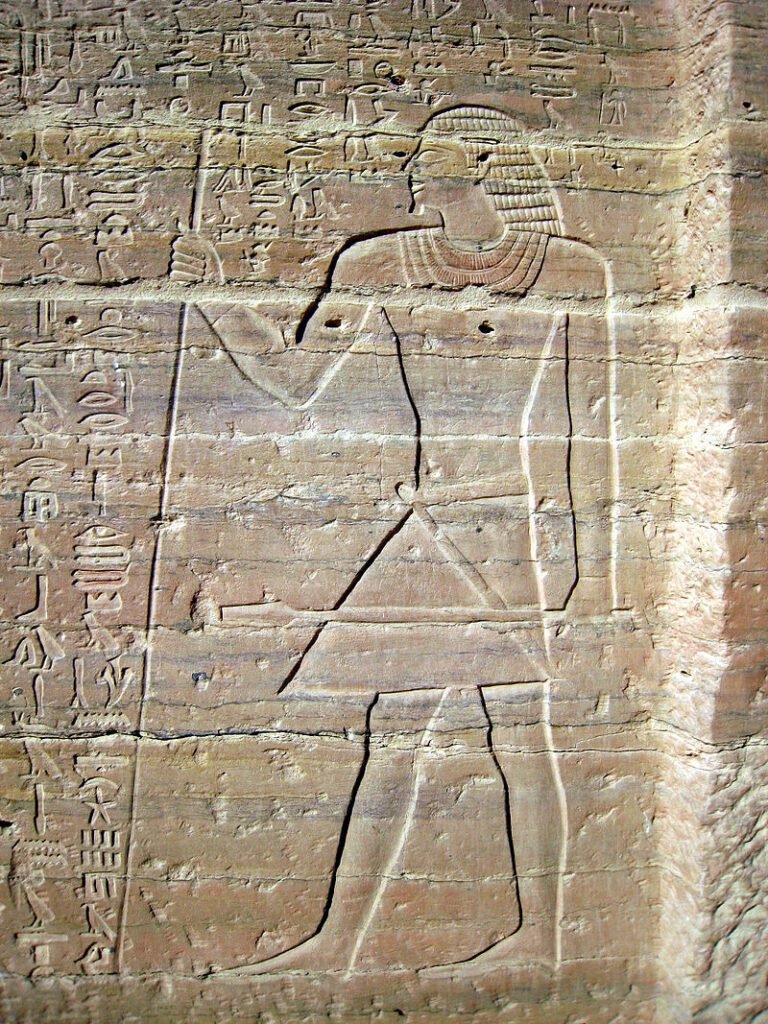

An undeniably important element of the history of foundations is the role they have played as vehicles for commemoration, celebration and the cementing of social status. For as long as people have been performing charitable deeds, they have been keen to ensure that people know about them and remember them after they are gone: a tomb inscription from around 2300 BCE, for example, lists the charitable gifts of the Egyptian nobleman Harkhuf along with a declaration that he had given these gifts because “I desired that it might be well with me in the great god’s presence”. Bequests, eulogies, statues and plaques continued to play a key role in celebrating charitable gifts and the donors who gave them for the next 4,000 years, and as foundation-like structures became more common they played an increasingly important role as vehicles for commemoration as well. W.K Jordan argues in his Philanthropy in England 1480-1660 that the proliferation of charitable trusts during this period was driven in part by a desire on the part of wealthy London merchants to secure their lasting reputation as generous benefactors, and also by the desire of more modestly wealthy merchants in provincial towns around the country to emulate them.

(Image by Karen Green, CC BY-SA 2.0)

There has always been a suspicion, however, that the purpose of some foundations and foundation gifts is not merely to commemorate the donor and their family, but to craft a deliberate lasting narrative about them that is perhaps more favourable than the one they might get if people only remembered them for their business dealings or wealth creation. Figures like Andrew Carnegie and John D Rockefeller are known by many today primarily through their philanthropic legacy and the foundations that bear their name (which have undoubtedly done huge good in the world over the last century), yet during their own time they were hugely controversial figures – criticised by many as “robber barons” whose business practice were ruthless and unethical and could not be outweighed by any amount of good deeds. The writer G.K. Chesterton penned an excoriating attack on Rockefeller in 1909 entitled “Gifts of the Millionaire”, in which he wrote that:

“Philanthropy, as far as I can see, is rapidly becoming the recognisable mark of a wicked man. We have often sneered at the superstition and cowardice of the medieval barons who thought that giving lands to the Church would wipe out the memory of their raids of robberies; but modern capitalists seem to have exactly the same notion; with this not unimportant addition, that in the case of the capitalists the memory of the robberies is really wiped out.”

Perhaps the modern apotheosis of the idea that foundation philanthropy can be used to craft a positive narrative is, of course, the Sackler Family. For a long time, the Sacklers were known primarily as generous donors to museums and art galleries, and most people probably had little or no idea how they had actually made their money. That all changed as the story gradually came to light of the role that the Sackler’s company Purdue Pharma played in creating and exacerbating the opioid epidemic that is still blighting the US. Now the Sacklers are a byword for tainted money, and an easy go-to example for anyone who wants to argue that philanthropy is a tool for reputation laundering.

(Image by Geographer. CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Sackler story certainly offers a cautionary tale for philanthropy in many different ways; one of which is a reminder that the commemorative role of foundations can be abused, and that this is something we need to guard against. But we should also be careful, as with so many things about philanthropy, not to tip over into blanket cynicism and assume that all commemoration and celebration through foundations and their gifts is therefore illegitimate. What about the many examples in which people have set up foundations in memory of loved ones who have died in order to support work that might address the factor that caused their death and perhaps prevent others from dying in similar ways? Or the examples of famous actors and sportspeople who set up foundations in their own name in order to take advantage of their celebrity to raise awareness and support for particular causes? More often than not we welcome these (and rightly so), which suggests that it is not necessarily using foundations for commemoration and celebration per se that we object to; rather it is a more complex question of the way in which it is done and the motives we perceive to be driving it.

Putting wealth in context

The final point to make is that foundations clearly don’t exist in a vacuum. If it was ever genuinely true that the “left hand” of giving wealth away could be kept separate from the “right hand” of how it is created in the first place, that is certainly not the case today. The controversy over the Sackler family mentioned above is just one example of an increasingly sharp focus on the question of how money has been made and how this affects the legitimacy of trying to do good (and earn reputational rewards) through giving it away. This is not just about money that is being made now, either, since many argue that we need to examine the historical roots of foundation assets in order to understand whether they are direct or indirect products of injustices in the past, through slavery or other exploitative practices; and if so, whether we need to address this through recognition or reparation of some kind.

Putting foundation assets in context is not just about where the money came from in the first place, though – it is also important that we understand how that money is used once it has passed the threshold to become philanthropic capital, but before it is given out in grants or used to fund operations, and the question of how endowments are invested is a crucial part of current debates about foundations. Ben Whitaker noted back in 1974 that:

“Most foundations have viewed their investment policy and their program activities as two entirely distinct matters. Only a small minority of radicals have felt that this attitude contains an inherent anomaly: that foundations could, with their traditional investments, be helping to conserve the very society which their programs were attempting to rectify.”

Thankfully the view that foundations need to consider how their investment align with (or, indeed conflict with) their mission is no longer the preserve of a “small minority of radicals”, but neither is it universal yet by any means. The field of mission related investing (MRI) by foundations is certainly growing, but the number of foundations that have made 100% of their assets fully mission-aligned remains relatively small. The danger here, as pointed out by Whitaker, is that if foundations don’t take an MRI approach, there is always a risk that they will be investing their assets in activities that exacerbate the very problems they are trying to address through their grantmaking. And in fact the problem is worse than this: since the reality is that for most foundations which follow the traditional model of making grants out of returns made on their investments, those grants only ever represent a small fraction of the total assets available to the foundation, so if the far larger amount of endowed assets are invested in ways that do harm, then those harms might well vastly outweigh any good the foundation is ever able to do through its grants. Which is why many feel that the conversation on how foundations can use the full range of their assets more effectively for social impact needs to be moved forward far more quickly.

So What Now?

That was clearly a pretty long journey through the historical context for foundations and where things stand in terms of current debates about their role, so I won’t add too many words now trying to draw everything to a neat conclusion. The main point is that the foundation structure has, in one form or another, been around for a long time, which suggests that it has proven itself useful and that it perhaps reflects something fairly fundamental about the nature of philanthropy. As such, we should be careful about being too hasty in concluding that foundations have had their day, or that the model needs to be abandoned. (Since I strongly suspect that we would end up re-inventing something that looked distinctly foundation-like anyway!) But, as we have also seen, foundations have always attracted criticism and controversy; so even as we accept them as a necessary and important part of the philanthropic landscape, we should acknowledge that there are many questions still to be asked and that these don’t always offer easy answers.