29th June 2022

As political controversy over food banks rages once more, we take a look at the deep historical connections between philanthropy and how we understand poverty.

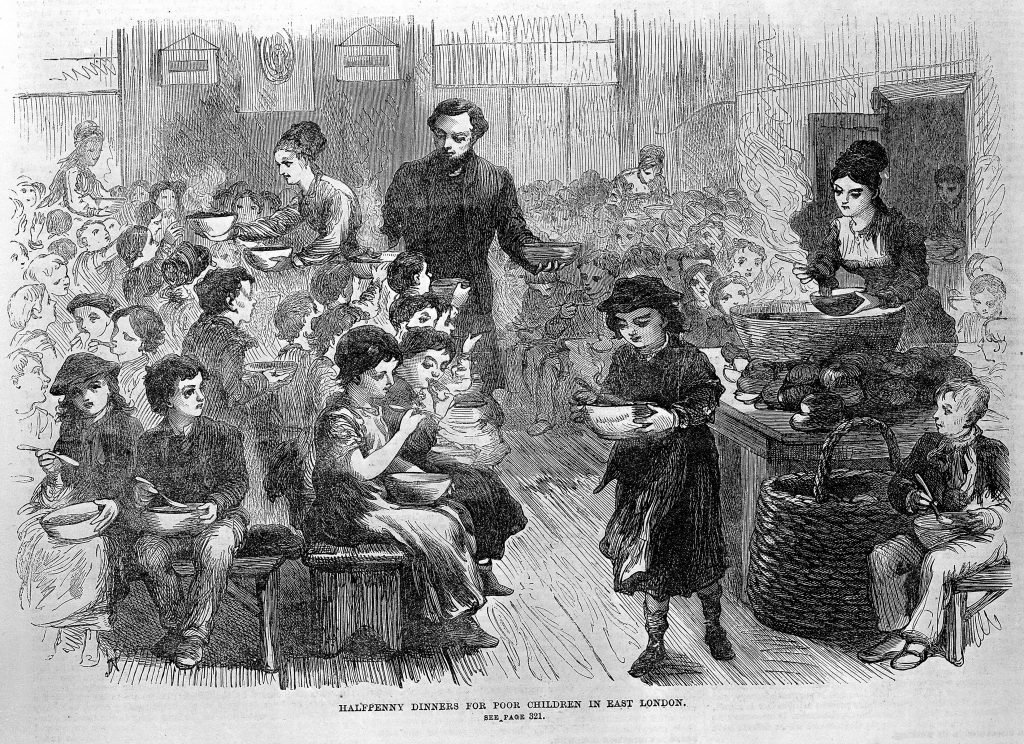

A UK Member of Parliament, Lee Anderson, caused a furore this week by claiming that the rise in people using food banks is partly down to people “not being able to cook or budget properly”. Critics accused him of being “out of touch” and holding “Victorian” views on the nature of poverty and charity. But his comments betray an ideological view whose roots in fact go back much further than the Victorians. The two key elements of this worldview are a belief that poverty should be seen as an individual moral failing, rather than a reflection of structural flaws in society; and the idea that when it comes to addressing poverty we should distinguish between those who are the ”deserving” recipients of our charity or sympathy, and those who are “undeserving”.

This is a viewpoint with a long history – a history that it is vital for those working in philanthropy and civil society to understand for several reasons. For one thing, punitive and judgmental views of poverty are far from uncommon. There are still many people who believe that those in poverty are to some extent there as a result of their own lack of moral fibre or work ethic; or that being poor represents some kind of choice. Dog-whistle rhetoric about “benefits scroungers” and “welfare queens”, meanwhile, is commonly used by critics of state welfare to whip up resentment among voters or taxpayers by stoking fears that they are being taken advantage of by others who are gaming the system.

More stringent methods of distinguishing between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor through means testing or stricter eligibility criteria are often presented as the solution to these problems, even if this comes at the cost of making it harder for those in genuine need to claim the support to which they are entitled. For civil society organsiations, it is important to understand such views so that they can counter them effectively. And indeed, this week saw many poverty charities and campaign groups speak out critically against Lee Anderson’s claims.

But there is another reason civil society needs to engage with these ideas; and one that brings to light an uncomfortable truth. The fact is that distinctions between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor have throughout history been inextricably linked to views on charity and philanthropy, because the way we think about charity has been a major driver for the enduring power of this idea; and conversely the idea has shaped the ways we give and the way charitable organisations work. Some would even argue that it continues to do so today; and is still problematically embedded in the very structures we use for funding and delivering support to those in poverty.

It is important, therefore, that we understand where these ideas have come from and how they have influenced our views and practices if we are to move beyond them and avoid letting them undermine efforts to address poverty. In this article I am going to sketch out some of that history and ask where it leaves us as we look to the future.

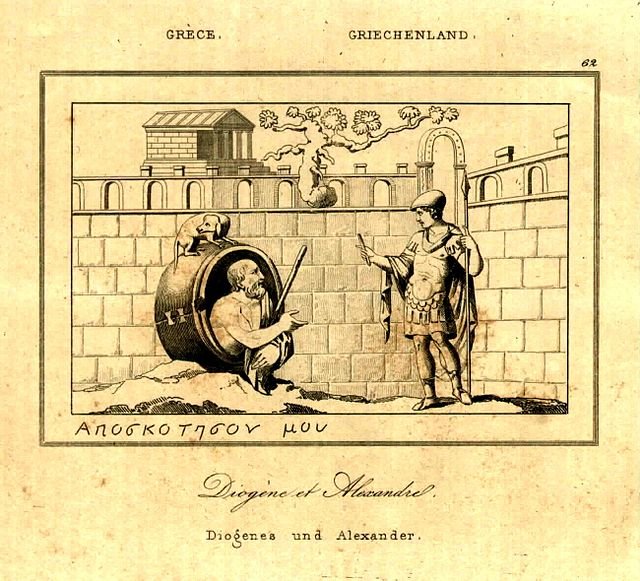

Classical Roots

The Ancient Greeks and Romans had very different notions of poverty and how it should be addressed within society to those we hold today (or, at least, to the views most of us hold…) So, we should be careful about assuming that language and concepts translate directly, since many scholars would argue that there are significant discontinuities we need to take into account. However, it is worth looking at how notions of poverty in the classical word related to their ideas regarding philanthropy, as we can certainly identify elements that seem to have crept back into later thinking.

The first thing to note is that when talking about “the poor”, the Greeks and Romans generally weren’t using the term to imply people in absolute poverty or destitution. Rather, as the classical scholar A. R. Hands notes, they were referring to “the vast majority of the people in any city-state who, having no claim to the income of a large estate, lacked that degree of leisure and independence regarded as essential to the life of a gentleman”. These people were seen as “poor” not because they were on the breadline, but because they had to endure (in Juvenal’s words) “the degradation of having to work”. The attitude of wealthier citizens towards these toilers was one of mild contempt rather than pity, and they certainly didn’t feel obliged to give to them simply because of their lack of wealth.

The Greeks and Romans did of course understand that there might be those who existed in something more like genuine poverty. In some case this would have been because illness or injury prevented people from working, and in these circumstances the individuals in question might have received some sympathy (although probably not much — these were, after all, societies that viewed weakness with disdain and went so far as to dispose of unwanted children by deliberately exposing them to the elements). In the case of those who were able-bodied but not working, however, they would be viewed as beggars and treated with little or no sympathy at all. It is noted, for instance, that in the plays of Aristophanes “beggarly poverty is painted without love and almost without pity”. This was largely because in Ancient Greek and Roman society unemployment was seen as an entirely avoidable evil that could be dealt with through legislation (or alternatively by banishment), so it was assumed that anyone not working had chosen to do so and thus deserved no sympathy.

As a result of all this, alleviating poverty was not really a focus for philanthropic giving in the ancient world. However, we can still find the idea that we must differentiate between deserving and undeserving cases beginning to emerge. As Hands notes “the emphasis in classical literature is not ‘give to the penniless’, but ‘give to the good when they ask you’”, and this idea that recipients must be ‘worthy’ or ‘deserving’ was echoed by many thinkers including Aristotle, Cicero, Cato and Theognis, so “the generous man would not give to ‘any Tom, Dick or Harry’”. We can also discern early versions of an idea that was to come back with a vengeance in subsequent millennia: that giving in an indiscriminate way to those who were “undeserving” was not only wasteful from the donor’s point of view, but actively harmful to the recipient, because it undermined independence and the drive to self-help. Hence Plutarch quotes a Spartan replying to an entreaty from a beggar: “But if I gave to you, you would proceed to beg all the more; it was the man who gave to you in the first place who made you idle and so is responsible for your disgraceful state.”

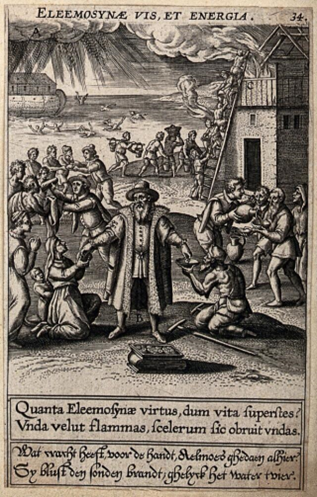

Medieval Charity

Views on the nature of poverty and giving (in the Western world at least) began to change with the rise of Christianity. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and the subsequent rise of the Byzantine Empire in the East, the Judeo-Christian notion of Caritas (charity) gradually took prominence over the Greco-Roman concept of philanthropy, and this went on to shape medieval thinking.

For most medieval thinkers, poverty was not a problem that could be “solved“, but rather an unavoidable (and perhaps even actively desirable?) feature of the world. As historian Suzanne Roberts writes “Medieval charity never intended to eliminate or solve social problems. Medieval people had no social theory of poverty, and they did not expect to change the social order; following Saint Paul, they believed that the poor would always be among them”. So poverty was assumed to reflects God’s design: some people are poor whilst others are rich, and that is just the way things were. The poor could enjoy the knowledge that they were closer to God, since poverty was a virtue (even if they may not have felt especially lucky at the time…). The rich, meanwhile, had a duty to offload the spiritual burden that came with wealth by giving alms to the poor. There was no sense, however, in which that the purpose of the giving was to try and alter this order in any way.

It is worth noting that this is closely linked to medieval Christian thinking on the nature of property. According to the teachings of the time, the rich were not owners of their worldly property, but merely stewards during their lifetimes, with a duty to give back to the poor through almsgiving. As Thomas Aquinas put it in the Summa Theologica: “man ought to possess external things, not as his own, but as common; so that, to wit, he is ready to communicate them to others in their need”. Furthermore, it was seen as a good thing that there were poor people — both because they were themselves closer to God (hence the famous teaching that it was easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven), and because the presence of the poor offered an opportunity for the rich to prove their worth through charity.

As a result of all this, notions of Christian charity differed sharply from Greco-Roman concepts of philanthropy — both in emphasizing care for the poor and in placing the focus on what the act of giving meant for the donor (rather than on what the gift achieved necessarily). The caricature view of Medieval almsgiving, therefore, is that it was entirely undiscriminating and distributed to anyone in need or apparent need without any determination of whether they were “deserving” or not. However, whilst this might have been true of a lot of giving during the early Medieval period, the picture became more complex as time wore on. Periods of famine and war brought new economic challenges, and as a result poverty increased in scale and intensity. In order to address this, many began to return to the idea of distinguishing between the deserving and undeserving poor. The historian Brian Pullan notes that Catholic legal scholars as far back as the 12th and 13th centuries who were commenting on Gratian’s Decretum had established an “order of charity”, which recommended a range of criteria for determining between more and less deserving cases when giving larger amounts. Suzanne Roberts, meanwhile notes that: “As the social function of charity became increasingly important, the balance of religious and administrative concerns which characterized the high Middle Ages shifted. The evangelical conception of charity with its inclusive attitude towards all the needy began to want. The discriminating model, with its concern for wise allocation of limited resources, seemed a better guide for giving in a difficult and uncertain era.”

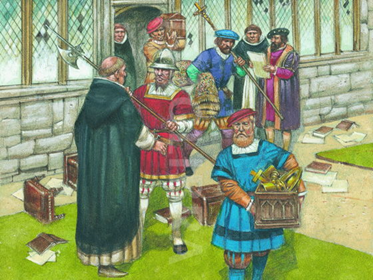

The Reformation & the Poor Laws

The Reformation in the 15th century had a big impact on the ways in which people thought about and practiced charity. Henry VIII’s decision to split from the Catholic Church following the Pope’s refusal to endorse his wish to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, led to the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the systematic seizing by the State of many of the assets of Catholic institutions in England. As a result, according to historian Paul Slack, “the Reformation destroyed much of the institutional fabric which had provided charity for the poor in the past: monasteries, guilds and fraternities.”

At the same time Protestants were promoting a new approach to charity that claimed to be based on meeting the immediate needs of society rather than the needs of the donor’s immortal soul. Influential preachers like Thomas Becon gleefully lambasted medieval Catholic charity, claiming that it had “perverted the charitable impulse” by “persuading amiable but misguided men to pour funds into great monasteries for the bellied hypocrites… and free chapels for soul-carriers and purgatory-rakers.” Protestant charity by contrast, they claimed “was characterised by modesty and by the effective concentration of resources on pressing areas of human need”. Unsurprisingly, the idea of being discriminating when it came to the recipients of charity was at the heart of this new approach.

The gap left by the deliberate destruction of so much of the medieval Church apparatus for aiding the poor also brought new challenges for Tudor society. By the end of the 16th century, problems of poverty were so severe that the government was forced to introduce Poor Law legislation. The state now accepted, for the first time really, a measure of responsibility for the welfare of its citizens; a responsibility which had previously been thought the rest with the family or the church. As this required the introduction of local levies to pay for any welfare needs, all citizens now had a stake as taxpayers; which meant that many were keen to ensure that their money was “well spent” and did not go to “the wrong people”. Hence the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor became more important than ever.

Whilst the Tudor government had been forced to introduce Poor Laws on paper, however, they were keen — as far as possible — to avoid having to implement them in practice (particularly as it meant imposing deeply unpopular taxes). That is why the introduction of English Poor Law Legislation in 1598 was swiftly followed by the introduction of the Statute of Charitable Uses in 1601: this latter legislation was primarily designed to make charitable endowments more “effective” by directing them towards causes that were in line with the government’s own policy priorities. That way the burden of state responsibility for welfare could be lessened. But in order for this to work, it was more important than ever for there to be a sharp focus on ensuring that giving was suitably discriminating. As historian Paul Slack argues, “the poor law set out to reform remodel charity. It should be purposive and discriminatory. Begging and casual almsgiving were to be abolished. The generous instincts of donors should be disciplined by attention to the recipients.”

The Enlightenment, Industrialisation and Associational Philanthropy

Historians sometimes talk about “the long 18th century” (typically taken to span from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 to the Battle of Waterloo in 1815), and this is certainly a period that saw seismic shifts in our understanding of poverty and the ideas and practices of philanthropy. The radical new political and economic developments of The Enlightenment, for instance, led people to believe for the first time that poverty might be a structural problem that could potentially be corrected; rather than simply a permanent fact we must accept (as the medieval view would have had it). Views on the nature of this problem differed widely, however. One school of thought (stemming from the work of thinkers such as Grotius, Pufendorf and Locke) argued that property ownership was a matter of natural rights — so those who had wealth had earned it by the sweat of their brows, and those who didn’t were clearly just not trying hard enough. This once again gave rise to the idea (last seen among the Greco-Romans) that poverty was primarily a result of lack of character or willingness to work on the part of the individual, and that charity must be therefore discriminating for fear of breeding idleness and reliance. Hence we have the philosopher David Hume arguing that “Giving alms to common beggars is naturally praised; because it seems to carry relief to the distressed and indigent: but when we observe the encouragement thence arising to idleness and debauchery, we regard that species of charity rather as a weakness than as a virtue.”

At the same time another school of thought emerged, which argued that whilst the distribution of property in the world was not ordained by God, it was also not reflective of individual merit and labour; rather it was a result of unfair and inequitable laws and systems that advantaged some at the expense of others. Those who took this view argued that in one sense the poor were all deserving: not of charity, however, but of justice, since they had the right to demand the share of society’s wealth to which they were entitled but had been denied.

Hence we have the pioneering women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, declaring that “it is justice, not charity, that is wanting in the world” but arguing that to the rich “the rights of men are grating sounds that set their teeth on edge” so that “if the poor are in distress, they will make some benevolent exertions to assist them; they will confer obligations, but not do justice.” Her husband, the political philosopher William Godwin, agreed — decrying what he saw as “a system of clemency and charity, instead of a system of justice”, which resulted in the poor being forced into a position of servility in which they “regard the slender comforts they obtain, not as their incontrovertible due, but as the good pleasure and grace of their opulent neighbours.” Even the philosopher Immanuel Kant, not normally seen as a radical, argued in his Lecture on Ethics that “although we may be entirely within our rights, according to the laws of the land and the rules of our social structure , we may nevertheless be participating in a general injustice, and in giving to an unfortunate man we do not give him a gratuity but only help to return to him that of which the general injustice of our system has deprived him.”

The other major impact on philanthropy during the long 18th century came from industrialisation and urbanisation. As populations shifted from rural areas into rapidly growing towns and cities to find new work in the factories and mills that sprang up around the country, the nature and scale of issues of poverty, disease and ill health changed too. New methods of charity were therefore needed since, according historian David Owen, “it was out of the question for the philanthropist, however well disposed, to seek out the cases of greatest need and become familiar with them… to translate the person-to-person charity from the village or the small town to an urban slum was an impossible task.” One result of this was the growth of “associated philanthropy”, modelled on the new joint-stock corporations that emerged at around the same time, in which donors could come together in order to pool resources in an intermediary organisation that could then draw in additional expertise to ensure money was wisely and effectively distributed. This effectively marked the birth of the voluntary organisation as we know it today, and the model proliferated rapidly. The ongoing fear of indiscriminate giving was an important element in this growth because, as historian Michael Roberts notes, “the claim to be able to resolve the dilemma of the culturally sensitised yet apprehensive giver — a giver afraid of wasting resources on the relief of less needy (and often deceitful) supplicants) — was to be a mainstay of charitable associational self-justification throughout the next 150 years.”

The Victorians: Indiscriminate Giving & Charity Organisation

The introduction of the Census in 1801 laid bare for the first time the scale of poverty in the new urban society of the UK. For some this was a clear basis for demanding that the state should take a greater share of responsibility for meeting welfare needs. However, for others philanthropy was the solution, and for the majority of the 19th century their view won out. An 1865 editorial in The Times neatly sums up this Victorian view of the desirability of voluntary, rather than state, welfare provision:

“Among the many considerations which make an Englishman proud of his country there is hardly one which can so justly excite his patriotic satisfaction as the contemplation of its vast, numerous and richly‑endowed charities. Much of that which the church or the state has collectively done in other countries, the voluntary benevolence of individuals has done in this . . . It is this spontaneity of action which distinguishes our social, as it distinguishes our legislative proceedings. We do not wait for the instigation of the Government or the dictation of a central bureau. The individual eye sees, the individual hand indicates, the social malady. Individuals’ charity finds the remedy. If the experiment succeeds, Parliament and Government follow in the wake, often after an interval of years. But it rarely, very rarely happens that in England any great scheme of comprehensive benevolence is initiated by the Government, which is only too happy to await the results of private enterprise and private experience.’”

As a result of this reliance on philanthropy to meet the needs of society, there was more focus that ever on the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor, and the idea that giving need to be discriminating. To the extent, indeed, that the “indiscriminate alms-giver” became the go-to bogeyman for many Victorian philanthropists. Dr Guy, for instance, wrote that :

“if you will somehow contrive to handcuff the indiscriminate alms-giver, I will promise you for reason I could assign, these inevitable consequences: no destitution, lessened poor rates, prions emptier, fewer gin shops, less crowded mad houses, sure signs of underpopulation, and an England worth living in.”

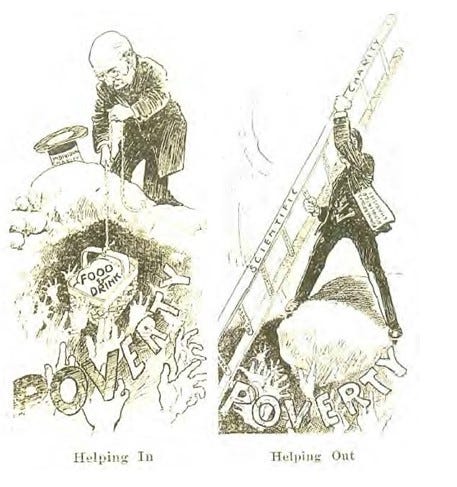

We have seen already that the development of voluntary associations in the 18th century was in part driven by a desire to assuage such concerns, and to reassure donors that their giving was systematic and discriminating. However, this was not enough. As the 19th century wore on criticisms of indiscriminate giving grew louder, culminating in the creation in 1869 of the London Society for Organising Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicity (better known as the Charity Organisation Society, or COS). The COS’s mission was to challenge perceived laxity and inefficiency in charitable giving and Poor Law administration, and thus to put the relief of poverty on a more “scientific” footing. It pursued this mission with the zeal of a religious crusade and in doing so made many enemies — in large part due to its tendency to single out individual charities and philanthropists for harsh criticism, and its uncompromising dismissal of anyone who did not agree with its principles and methods. The COS had many supporters, too, however — including notable philanthropists such as Octavia Hill and William Rathbone VI — and its reach spread throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the creation of many local COS chapters across the UK and in the US.

The movement had a particularly notable effect in America, where the concept of charity organisation was combined with growing enthusiasm for the evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin and the ideas of thinkers like Herbert Spencer to create a new form of “scientific philanthropy”. This became a major influence on some of the biggest-name philanthropists of the time (and, indeed, of all time). For men like John D Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, the challenge of giving away large sums of money in a way that they would consider effective was almost paralysing; hence Carnegie’s famous declaration that “it is more difficult to give money away intelligently than to earn it in the first place”. Scientific philanthropy provided both men (and many of their contemporaries) with a framework for giving large amounts in a systematic fashion (whilst also justifying an emphasis on individual responsibility and self-reliance that fit conveniently with their existing views about wealth and society).

Whilst scientific philanthropy had many advocates in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were also plenty of critics, who saw its focus on discrimination in giving as cruel and dehumanising. These critics often drew comparisons with the humanity and basic kindness at the heart of Christian charity and argued that losing these was too high a price to pay for “efficiency” or “rationality”. The Irish-Amercian poet John Boyle O’Reilly mocked what he called “the organized charity, scrimped and iced, in the name of a cautious statistical Christ”; whilst the writer Ambrose Bierce acknowledged that “indubitably much is wasted and some mischief done by indiscriminate giving” but argued that “there is something to be said for “undirected relief” all the same” because “it blesses not only him who receives, but him who gives”. The American social reformer Jane Addams, herself a noted philanthropist, likewise wrote that “even those of us who feel most sorely the need of more order in altruistic effort and see the end to be desired, find something distasteful in the juxtaposition of the words “organized” and “charity”… at bottom we distrust a scheme which substitutes a theory of social conduct for the natural promptings of the heart, even although we appreciate the complexity of the situation.”

The 20th Century: The Welfare State & its Discontents

The histories of philanthropy in the UK and the US diverge significantly from the start of the 20th century. In the US, the first half of the century saw the institutionalization of philanthropy in the form of the great foundations emerging from vast industrial and financial wealth. The ideas of scientific philanthropy were enshrined in the ethos and operating model of many of these institutions, and as such they came to define the template for philanthropy. A template that has subsequently evolved into models of “effective” and “strategic” philanthropy that still dominate a lot of thinking about philanthropy even today.

Philanthropy in the UK, as in many other places around the world, has been influenced by the developments in the US — particularly since the latter half of the 20th century. But our own history developed quite differently, and this has shaped thinking on the nature of poverty and charity in a distinctive way.

By the end of the 19th century, there was a growing sense that the grand Victorian experiment of meeting the welfare needs of society through philanthropy had failed. Benjamin Kirkman Gray, surveying the situation in 1905, wrote that “private individuals were confident of their power to discharge a public function, and the government was willing to have it so. It was left to experience to determine that the work was ill done and was by no means equal to the need.” There was also growing distaste at the perceived moralistic and paternalistic nature of a lot of philanthropy (of which the relentless focus on identifying the “deserving poor” was a major part). This led to more focus on the role of state in the early 20th century; first from Liberal governments who introduced new measures like the National Insurance Act, and then subsequently from the Labour government that swept to power following WWII and launched the welfare state.

This brought with it much more critical views about philanthropy and charity, and the selective and discriminating nature of giving was often a central part of the criticisms. The Labour Health Minister Aneurin Bevan famously derided philanthropy as a “patch-quilt of local paternalisms” and declared in a speech to the House of Commons that “it is repugnant to a civilised community for hospitals to have to rely upon private charity.”

The vision for the welfare state was one of universal provision, so that it would now not be necessary to pick and choose who received support, or to assess whether or not they were deserving. However, over time it became clear that in reality there were many gaps in state provision that still needed to be filled by voluntary provision. The economic hardships of the post-War period also saw new dimensions of poverty emerge, to which the state did not always adapt that quickly. Many voluntary organisations therefore recast their role from one of service provision to one of advocacy and campaigning work designed to challenge the failings of the welfare state. This latter role became ever more important as changes across society in the 1960s and 1970s led to a new spirit of activism and demand for participation, and the formation of campaigning organisations such as Shelter and the Child Poverty Action Group, which played a vital role in challenging society’s understanding of poverty and its causes.

The end of the 20th century then saw the emergence of new political ideologies in the UK. The New Right conservatism of Margaret Thatcher’s governments, in addition to its embrace of markets and its disdain for state action, brought with it a return to a view of poverty as an individual failing and a view of charity that emphasised the need for discrimination and the importance of self-reliance. The New Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown then represented a reaction in many ways to this view- once again embracing the idea that poverty should be seen as a structural and systemic issue. Although in linking the “rights” to welfare provision through the state to the “responsibilities” of meeting the expectations of good citizenship, they carefully echoed the idea that some might be view as deserving whilst others were undeserving (presumably in order to assuage those voters for whom this was a requirement).

The Thatcherite and Blairite governments had widely differing views of the role of charities in many respects, but one element common to both was a focus on outsourcing as the template for the relationship between state and voluntary sector. They implemented this idea in different ways: the Conservatives focusing initally on a model of competitive tendering that pitted charities against private sector organisations, and Labour subsequently adopting a model centred on the active commissioning and procurement of services. However, both had at their core the idea that whilst voluntary organisations should definitely be involved in welfare provision, instead of doing it separate from or alongside the state, they should do it on a contractual basis on behalf of the state. This meant that the balance of power in determining which needs were to be met, and how, was shifted heavily away from the voluntary sector and into the hands of the state. As a result, the government’s views on the nature of poverty and the potential distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor came to shape how many charities delivered their services.

What Now?

It should be clear that the debate over whether poverty reflects a structural failing or an individual one has been around for a long time, as has the idea that some poor people are “deserving” of our help. When politicians or commentators make statements denying the structural roots of poverty and suggest that it represents some sort of failing on the part of poor people themselves it is understandable (and in my view essential) that charities and civil society organisations speak out and challenge them. However, as we have seen, it is important to understand that the historical roots of these ideas are inextricably tied up with our notions of charity and philanthropy. Therefore, we also need to turn the lens inwards and question whether these same ideas continue to exert a hold over (and some would say hold back) the work of philanthropy and charitable organisations when it comes to addressing poverty even today.