29th June 2022

Following concerns about links between social good tech provider Blackbaud and the NRA, we assess how this fits into wider debates about “tainted” money and the ethics of tech platforms.

There was controversy in the nonprofit sectors on both sides of the Atlantic this week, thanks to a TechCrunch article exposing the long-standing and seemingly very close relationship between “social good” cloud computing provider Blackbaud and the National Rifle Association (NRA). In the wake of another spate of tragic school shootings in the US, which has once again brought criticism of the NRA’s lobbying and its role in undermining calls for tighter firearms restrictions, many raised questions about whether Blackbaud’s ongoing ties with the organisation are ethically defensible.

This would probably have generated debate if any company had been at the centre of the story, but the fact that Blackbaud is almost certainly the biggest provider of software and platform services in the nonprofit world (it makes market-leading products like the fundraising CRM software Raisers Edge, and has also owned the UK’s well-known JustGiving platform since 2017) means that many organisations have skin in the game and now find themselves having to grapple with what these revelations mean for them, so the issues are felt particularly keenly.

This story also sits pretty much at the centre of a Venn diagram of some of the topics I am most interested in, namely:

- How should we deal with “tainted money” in philanthropy?

- What responsibilities do giving platforms have in terms of where they take money from and where they allow it to go?

- Are there are limits to the idea that plurality in civil society is an inherent good? (And who gets to decide where those limits are?)

- Is the idea of social good in the corporate world in danger of being used as a tool for “purpose washing”?

Given that (and given that I have had quite a few conversations about this in the last few days with various people!) I thought I would offer a couple of thoughts on the key questions and issues.

Is this an example of the “tainted money” problem?

When I first saw this story, I immediately assumed it was just the latest example of the long-standing challenges posed by “tainted donations”: i.e. gifts made from wealth that has been created in ethically dubious ways, and therefore pose dilemmas for recipients about whether it is better to accept them — on the grounds that one can ‘put bad money to good uses’ — or to stay clear of them. (For more on the history of the tainted donations debate, check out this Twitter thread I made).

However, on further reflection I’m not sure this is quite right. We aren’t talking here about the NRA itself making donations to other organisations (which for many would be a clear red flag, although I am sure that there are also plenty of organisation that would be fine with taking the money). What we are talking about is whether dealing with a company that also deals with the NRA is morally OK. And it is worth parsing further what “dealing with Blackbaud” mean here, as this can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Some organisations may be receiving money in the form of donations or sponsorship from the company; others may simply use their software products; and others may just be recipients of donations made via Blackbaud’s various platforms.

When it comes to organisations receiving money directly from Blackbaud, we are fairly close to the standard problem of tainted donations i.e., it is OK to take “bad” money, or should it be refused/returned? I usually suggest 5 key questions to ask here:

- Why is the money deemed to be problematic?

- Can it be clearly demonstrated that some good is going to be done with the money?

- Does acceptance of the gift imply condoning the donor’s values or business activities?

- Is the donor going to get some clear reputational benefit from the gift (whether tangible in the form of naming rights/sponsorship etc, or intangible in the form of a “halo effect”)?

- Will the donor exercise any degree of control over how the donation is used?

My view is that the closer you can get to a situation in which the source of wealth is not unarguably toxic, the donor is getting little or no reputational benefit from their gift, and that donor is exercising little or no power over how the money is used, then the more likely it is that a case can be made for taking the money. (Although this is not an exact science, and these things very much have to be done on a case-by-case basis). In the particular instance of Blackbaud and the NRA the first question posed about is perhaps the most interesting, as rather than questioning the moral status of the donor themselves (i.e. Blackbaud) on the basis of something they have done, we are being asked to assess whether they are guilty by association with another party (i.e. the NRA) who are assumed to be morally problematic, which feels a bit different to many straightforward cases of tainted donations.

Blackbaud may well object that their relationship with the NRA is just one commercial relationship among many others, and that it is unfair to single it out in this way as grounds for questioning their ethics. However this may not be that strong a line of argument since, as the original article makes clear, a core part of the issue is that the company’s relationship with the NRA appears to be particularly close — going beyond simply offering software to encompass “managing sentiment” and other services — and it is this is giving other organisations reason to question the situation.

For organisations who are merely users of Blackbaud products, rather than recipients of donations or sponsorship, the situation feels less more akin to the concerns of consumers about companies they shop with (and in particular the questions social media users raise about whether they should stop using platforms like Facebook because of the activities of their parent companies). In some ways this seems less problematic than the donation case, since assuming there are viable alternatives to Blackbaud’s products, any organisation is presumably free to switch to them for whatever reason it pleases and does not necessarily have to justify that decision in the way that they would have to justify turning down a donation. (Although if there is a financial cost associated with switching providers, then presumably they would have to justify that?)

Then for those organisations whose only link to Blackbaud is that they may receive donations via the company’s platforms, the link becomes even more tenuous. Does a charity, for instance, which receives funding from an individual who has fundraised using the Blackbaud-owned JustGiving platform have any grounds for taking moral issue? The money has not come from Blackbaud, or from the NRA, and the charity has presumably had no say in the choice of platform, so on what basis could they object? (Other than that a small portion of the gift is going towards the platform’s operating costs). Which is not to say that a charity in this situation (or indeed one that has no links whatsoever to Blackbaud) cannot have views about the appropriateness of the company’s links to the NRA; it just means that the weight of the moral dilemma for their own organisation seems pretty negligible.

Would the same concerns apply to any other service provider?

When we get to the point of thinking about what organisations that merely use Blackbaud’s software or receive donations via their platforms should do, this raises another important question: should we be asking the same questions of all the other service providers they may have links with? Many nonprofits might be justifiably unhappy that their software provider has a cosy relationship with the NRA, but what about their bank, or pension provider or the social media platforms they use? If these companies also have relationships with the NRA or other organisations whose values and activities the nonprofit objects to, should they also stop using their services? We have seen some moves in this direction in the form of nonprofits trying to ensure their own ethical supply chains, and when it comes to social media platforms there have been occasional, more proactive calls to “delete Facebook” and the like. However, the reality for most nonprofits is that they are almost certainly using the services of companies who are also providing services to people and organisations the nonprofit may take issue with.

This recalls George Bernard Shaw’s somewhat pragmatic objection to the notion of tainted donations:

“Practically all the spare money in the country consists of a mass of rent, interest and profit, every penny of which is bound up with crime, drink, prostitution, disease, and all the evil fruits of poverty, as inextricably as with enterprise, wealth, commercial probity, and national prosperity. The notion that you can earmark certain coins as tainted is an unpractical individualist superstition.”

Shaw’s point is that financial systems are so interconnected that once you start questioning some money you might as well question it all. There is a slight air of “whataboutism” to this argument, and I’m not sure we should be so quick to conclude that there is no way of differentiating between better or worse ways of creating wealth, but it does bring home the point that if we are going to raise ethical concerns about where money has come from, we need to be consistent. In terms of the current situation with Blackbaud and the NRA, this doesn’t mean that we should dismiss nonprofits’ concerns, but we should put them in the wider context of whether similar concerns apply to other donors or service providers and what should be done about it if so.

The Responsibilities of Giving Platforms & Corporate Social Purpose

One potential response to the argument outlined above is to suggest that Blackbaud should not be viewed in the same way as all other service providers, and should in fact be held to a higher ethical standard. This might either be on the grounds that acting as a platform for philanthropic giving brings specific responsibilities, or because the company goes further and specifically positions itself as having a “social purpose” and providing products designed around “social good”.

The first rationale reflects a debate that has been brewing over the last couple of years about the rise of “platform philanthropy” and what responsibilities the organisations operating giving platforms bear in terms of who they accept money from and where they allow it to go. (I wrote a piece for Alliance magazine about the ethics of platform philanthropy in 2020 and took a deep dive into the topic in a recent episode of the Philanthropisms podcast). The default has always been to claim that such platforms are merely neutral intermediaries, but increasingly this claim has come under fire from those who claim that such neutrality is a myth and that purported decisions to remain neutral in reality almost always involve taking sides. (Global Giving, which is itself a platform, has led some really interesting work on these questions).

When it comes to the Blackbaud/NRA case, therefore, critics might argue that it is not enough for Blackbaud to defend their actions on the grounds that they are “merely a neutral intermediary” because they should be going further and actively taking an ethical decision to refuse to take money from (or pass money on to) certain organisations, even if those organisations are legally deemed to be legitimate. I have quite a bit of sympathy with this view, but it does raise some thorny questions. For example, who gets to decide what is or isn’t on the platform? And on what basis is the decision taken? Whilst as an individual I may have ethical qualms about particular cause areas or organisations (as, indeed, I very much do about the NRA), that is not really enough in organisational governance terms to justify barring them from a platform (unless I happen to be the founder/owner of the platform and can essentially impose my own views). In most case, it would be necessary to make a separate case from an organisational point of view for why doing business with the group or individual in person would be problematic. This could be on the basis of a principled argument that it would run counter to the values or morals of your own organisation, or it could be on the basis of a more pragmatic argument that doing business with that individual or group would bring reputational risk or damage your relationship with other stakeholders.

The latter can be a challenge because reputational risk is often hard to quantify, whilst the former assumes that your organisation has some clear and pre-existing statement of what its values and morals actually are. In the case of Blackbaud (and a growing number of others) this might be given greater weight by the fact that the company claims to have a “social purpose” and to strive for “social good”, which presumably means that they have views on what is good or bad for society. Critics might therefore argue that they should be in a better position to take a principled stand against the NRA. Of course, this assumes that we all agree on what “the good” is, but it is far from clear that this is the case. Civil society is an inherently pluralistic thing (as per Kendall and Knapp’s description of the UK charity sector as a “loose and baggy monster”). It encompasses a huge range of organisations, with views about the world that are just as diverse and contradictory as those of the individuals who make up our society. So whilst many with civil society will take issue with the NRA for its role in perpetuating the cycle of tragic shooting incidents in the US, others will see it as a defender of civil liberties and 2nd Amendment Constitutional rights. And others, even though they may not like the NRA itself, may believe that it is the fundamental value of civil society plurality that needs to be defended above all else, and thus argue that the inclusion of groups like the NRA may be the price we have to pay.

These are not simple issues, and they don’t lend themselves to simple answers. Which doesn’t mean that we should shy away from engaging with them, but does mean that we should acknowledge that the decisions giving platforms have to take about where to draw the boundaries of acceptability are far from straightforward.

What should nonprofits do about the Blackbaud/NRA story?

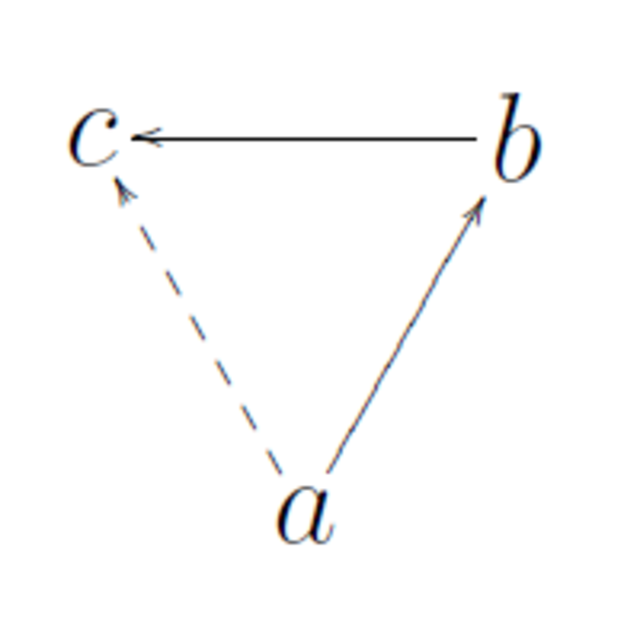

The key question for most organisations in the wake of the Blackbaud/NRA story is what (if anything) they should be doing about it. As we outlined above, this depends in part on whether they have an existing relationship with Blackbaud (and whether that is as a grant/sponsorship recipient, a service user or the recipient of donations made via a Blackbaud platform), but it also depends on unpicking some fairly deep and complex questions about civil society plurality, who defines social good, the responsibilities of platforms and the extent to which ethical concerns are transitive through customer relationships (i.e. If I do business with company A and they do business with questionable person B, does that mean I should be concerned about my links with B?)

Those organisations who currently use Blackbaud services and take issue with their relationship with the NRA are, of course, free to take their business elsewhere — either just to protect their own integrity or with the intention of using their consumer power to convince Blackbaud to re-evaluate its NRA links (although this would presumably require co-ordinated action from a larger number of nonprofit customers). For those organisations that receive grants or sponsorship from Blackbaud, meanwhile, the situation is a bit more complicated, since turning these down is a more intentional and symbolically-loaded act, so more thought needs to be given to the basis on which the decision is being taken and to the relative risks of taking or not taking the money. (As in addition to carrying a clear financial risk, turning down a donation may also bring its own reputational risk if other stakeholders take issue with the decision to do so).

None of which is to say that we shouldn’t take the concerns that this story has brought to light seriously, or do nothing in response to them. In fact, I would urge precisely the opposite: that all of us in the nonprofit world should being doing more when it comes to putting money in wider context. But I think that needs to go beyond just this one example; and that any response to the Blackbaud/NRA story should be focussed not just on the specifics of this case but on using it as a spur for putting in place principles and procedures that can guide future response in situations where it is necessary to scrutinise the sources of donations or question the ethics of commercial relationships and supply chains. Because, given the growth of platform philanthropy and the demands for greater transparency around sources of funding, it seems certain to be only a matter of time before another scandal like this comes along and raises all the same questions.