From the end of the mediaeval period growing numbers of people left rural areas – and a life of subsistence farming – and moved to the rapidly-expanding towns and cities: drawn by the prospect of jobs, wealth and a better life.

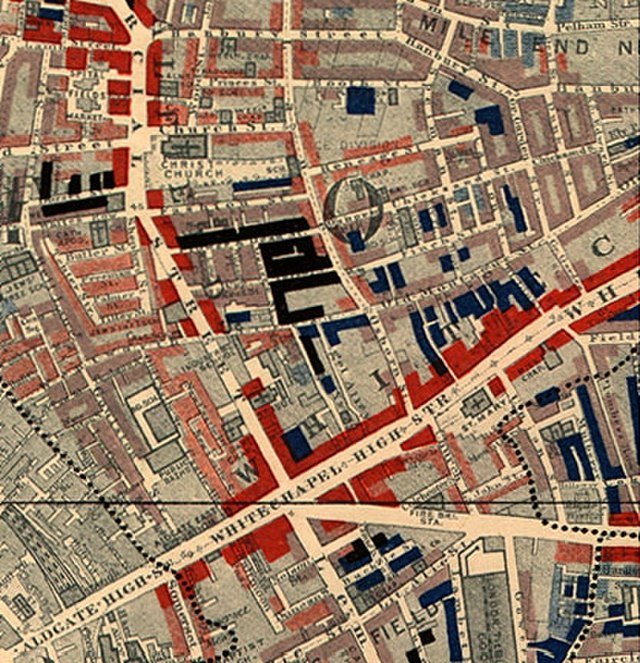

(Wellcome Collection, CC 4.0).

This phenomenon increased exponentially in the 18th and 19th centuries, driven first by the Agricultural and then the Industrial Revolution. New technologies and farming methods reduced the need for human labour and thus drove even more workers and their families out of the countryside and into the cities, where a huge range of new industries created vast demand for labour.

This shift had major implications for the development of philanthropy. The scale and nature of social problems changed dramatically: whilst there had always been rural poverty, those in the countryside were usually able to find work and had access to land on which to grow their own crops. In the cities, however, entire industries were often subject to massive fluctuations in demand so employment levels could drop to virtually zero, thus creating an entire new underclass of the unemployed.

These people no longer had the means to provide for their own subsistence, and the vastly increased population density meant that ill-health and disease were rife. Living conditions also had a dehumanising effect, and led to many knock-on effects in terms of increased crime and vice. Surrounded by squalor and degradation, human life often came to be seen as cheap, and problems like alcoholism and prostitution reached epidemic proportions.

The traditional methods and approaches of philanthropy were not suited to this urban environment. Philanthropy (and the almsgiving that preceded it) had been something that took place at a highly localised, parish level and, as David Owen argued, “to translate the person-to-person charity from the village or the small town to an urban slum seemed, and indeed was, an impossible hope.”

It had been possible previously to make decisions about where and how to give on the basis of seeing the problems and meeting those in need, to assess whether they were genuinely worthy of assistance. However, in an urban setting, this was no longer possible as there were simply far too many people in need for a philanthropist to interact with them all individually.

It became clear that the only way of dealing with urban poverty was to look for solutions to some of its underlying causes, and that philanthropy would have to change in order to do this.

This was one of the driving forces behind the development of “associational philanthropy”, which began in the mid 17th century. This period saw the birth of the ‘joint stock corporation’: a new structure allowing individuals to come together and pursue business interests collectively. At the same time, individuals also started to came together to pursue their philanthropic interests by pooling donations into intermediary organisations, which would then distribute them according to agreed criteria.

According to David Owen:

“It was out of the question for the philanthropist, however well disposed, to seek out the cases of greatest need and to become familiar with them. The consequence was, of course, to stimulate the growth of charitable societies serving as intermediaries between individual philanthropist and beneficiary… [Thus] the nineteenth century saw the charitable organisation come to full, indeed almost rankly luxuriant, bloom.”

These intermediary organisations were staffed by people who might not themselves be wealthy but had expertise and understanding of social problems, and were thus able to direct the resources of the wealthy more effectively. This is essentially the start of the modern notion of a charity as an organisation, which has proved to be an extremely enduring model.

These professional charitable organisations also brought with them a greater emphasis on using research and evidence – particularly the new methods of social science – in order to try to understand the nature and underlying causes of the challenges facing cities. The introduction of the Census in 1801 laid bare for the first time the true scale and nature of poverty, and figures like Charles Booth, the Rowntrees (Joseph and his son Seebohm), and the Webbs (Beatrice and Sidney) subsequently dedicated their lives to social research on the lives of the poor.

All this research had a huge impact on the understanding of poverty, as well as on views about the role of philanthropy. Once the scale of the challenge became clear, many came round to thinking that charitable efforts would never by themselves be enough and that further government intervention was needed. This eventually led to many changes in policy and practice that we can still recognise today, including the introduction of old-age pensions and the establishment of the welfare state.

The other major challenge in the newly urbanised setting was to ensure that people were still aware of the needs around them and thus motivated to give. At first this was not much of a problem because rich and poor tended still to live in close physical proximity, so it was impossible to ignore the reality of poverty and illness. The famous London philanthropist Thomas Coram, for example, often attributed his dedication to the cause of abandoned children (or “foundlings”) to his experiences of walking from his home to work in the City of London through a less salubrious area and seeing many deserted children but the roadside, both alive and dead.

However, as towns and cities grew, the poor became segregated into over-populated ghettos of low-quality housing (often in the shadow of the factories in which they worked), and those with wealth gravitated towards their own enclaves elsewhere. This meant that the lives of the rich could become dislocated from wider problems in society, which many worried led to the motivation to give becoming weaker.

Friedrich Engels (the future co-author of the Communist Manifesto) produced a report in 1845 on The Condition of the Working Class in Manchester, in which he identified the dislocation of rich from poor as one of the city’s major problems. The historian and former Labour MP Tristram Hunt recounts Engels perception of the situation:

“One of the most telling aspects of Manchester life was that the other half, the bourgeoisie, rarely had to come face to face with the horrors of proletariat existence. The divide between the two nations was more than financial. It was physical. The prosperous middle classes made their way to and from the city centre as the demands of their business necessitated. And on their way, according to Engels, ‘the members of this money aristocracy’ take a route which avoids them having to see ‘The grimy misery that lurks to the right and the left’… Engels believed he had never seen ‘so systematic a shutting out of the working-class from the thoroughfares, so tender a concealment of everything which might affront the eye and the nerves of the bourgeousie’.”

And this is still a challenge today. Modern research in the US has shown that wealthy people living in areas that are economically homogenous are less likely to give to charity than those in economically diverse areas. Although the good news is that that this seems relatively easy to tackle, as researchers found that the effect can be reversed simply by giving people a prompt (e.g. a short video on child poverty). As one of the researchers explains it:

“Simply seeing someone in need at the grocery store—or looking down the street at a neighbour’s modest house—can serve as basic psychological reminders of the needs of other people… Absent that, wealth will have these egregious effects insulating you more and more.”

As the graph above demonstrates, the world is continuing to urbanise. Right now, 55% of the global population lives in urban areas, and the World Bank predicts that this will rise to nearly 70% by 2050. Hence it is more important than ever that we understand the unique drivers and barriers for giving in the context of our towns and cities.