c.1900-1935:

Early 20th Century Growth of the State

Recognition of the need for state intervention has intensified by the end of the Victorian era, with a growing consensus that philanthropy could not by itself meet the needs of society.

The social historian Benjamin Kirkman Gray, writing in 1905, declares that “private individuals were confident of their power to discharge a public function, and the government was wiling to have it so. It was left to experience to determine that the work was ill done and by no means equal to the need.”

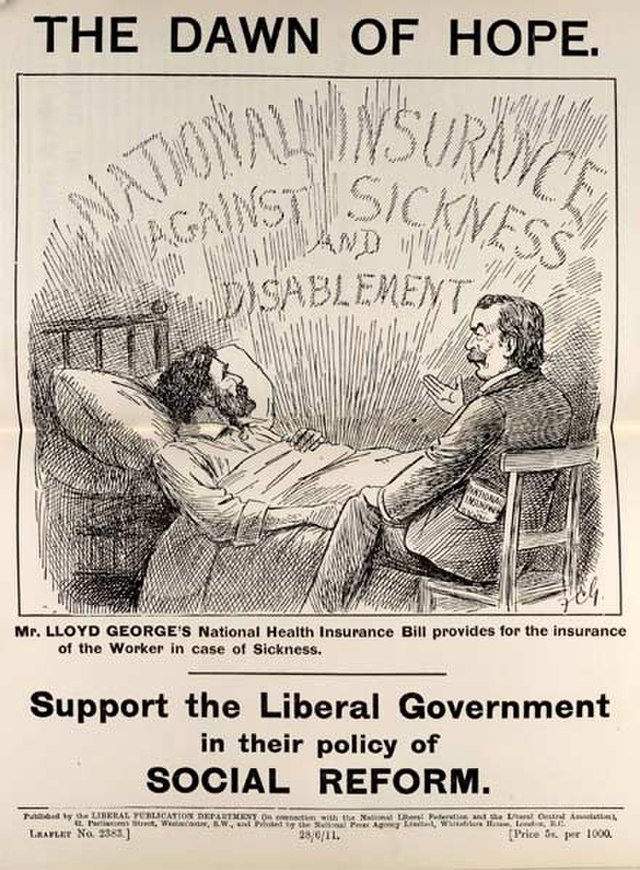

The Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 and the National Insurance Act of 1911 introduce new state mechanisms to provide for people no longer able to work due to ill health or old age.

The Liberal governments of the early 20th Century do, however, remain positive about philanthropy and voluntary action while laying the groundwork for far greater state involvement in welfare services. Winston Churchill, during his time as a Liberal, states a belief that it would be best to ‘underpin the existing voluntary agencies by a comprehensive system – necessarily at a lower level – of state action.’