Philanthropy has, throughout the ages, generated controversy of various kinds, as people object to who is giving, what they are giving to and how they are doing it. One particularly notable recurring theme is the belief that some donations are “tainted” because the money being given away was made in ethically dubious ways.

The question then, of course, is whether it is better to accept the gift in the hope of “putting bad money to good uses”, or to turn it down in order to avoid tainting oneself. This is a question people have been grappling with for as long as they have been giving to good causes, and opinion has always been divided.

The Venerable Bede, a monk who is sometimes known as the “Father of English History”, voiced concerns in the early 8th century that too much of the money being given to the church was coming from dubious sources. And in 746 the Council of Clovesho (a church synod attended by Anglo-Saxon kings) decreed that “alms should not be given from goods unjustly plundered or otherwise extracted through force or cruelty”.

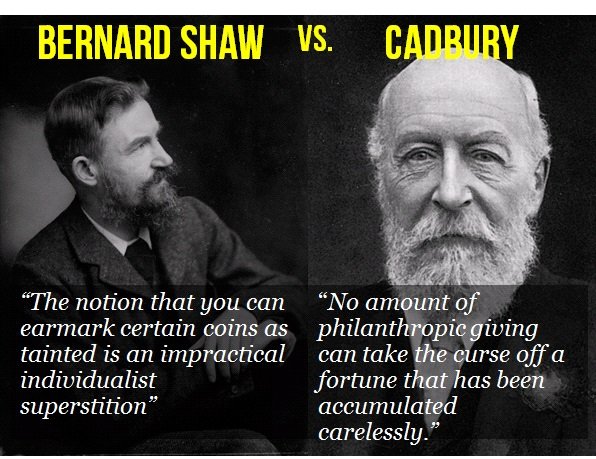

Likewise in the 19th Century the Quaker philanthropist George Cadbury took a holistic view of wealth: as the historian David Owen notes:

“Making money and giving it away formed for Cadbury a single pattern, and making it could be a constructive socially as giving it away. No amount of philanthropic giving could take the curse of a fortune that had been accumulated carelessly or without regard for the welfare of the workpeople who had labored for it.”

The American abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass was also a staunch critic of tainted donations. During his time in the UK in the 1840s, he helped to orchestrate a public campaign against the Free Church of Scotland’s solicitation and acceptance of gifts from American slave-owners- calling on the church to “send the bloodstained money back”.

Others, however, have argued that the distinction between “good” and “bad” money is unworkable and should therefore not be an impediment to philanthropy: according to George Bernard Shaw:

“Practically all the spare money in the country consists of a mass of rent, interest and profit, every penny of which is bound up with crime, drink, prostitution, disease and all the evil fruits of poverty as inextricably as with enterprise, wealth, commercial probity and national prosperity. The notion that you can earmark certain coins as tainted is an unpractical individualist superstition”.

And “General” William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, perhaps expressed it most clearly when he (somewhat apocryphally) said “the only problem with tainted wealth is t’aint enough of it!”

Tainted donations became a major source of political debate in the early 20th century US, thanks to a controversy in 1905 over whether the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions should accept a large donation from J. D. Rockefeller in light of concerns about his monopolistic business practices.

US President Theodore Roosevelt weighred in on the matter, arguing in a 1906 speech that “we should discriminate in the sharpest way between fortunes well won and fortunes ill won”, and that when it came to the latter, “no amount of charity in spending such fortunes in any way compensated for misconduct in making them.”

A number of high profile satirists couldn’t resist getting in on the act either. Mark Twain wrote a mocking letter to Harper’s Weekly in the guise of Satan which began: “Dear Sir and Kinsman – Let us have done with this frivolous talk. The American Board accepts contributions from me every year: then why shouldn’t it from Mr. Rockefeller…?””

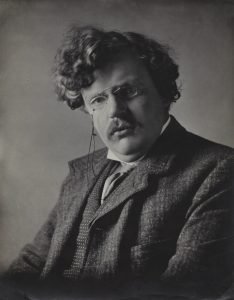

G.K. Chesterton, meanwhile, penned an article entitled “Gifts of the Millionaire” in which he poured scorn on Rockefeller’s philanthropy, arguing that it was nothing more than the latest in a long line of tawdry attempts to buy absolution through giving:

“Philanthropy, as far as I can see, is rapidly becoming the recognisable mark of a wicked man. We have often sneered at the superstition and cowardice of the mediæval barons who thought that giving lands to the Church would wipe out the memory of their raids or robberies; but modern capitalists seem to have exactly the same notion; with this not unimportant addition, that in the case of the capitalists the memory of the robberies is really wiped out. This, after all, seems to be the chief difference between the monks who took land and gave pardons and the charity organisers who take money and give praise; the difference is that the monks wrote down in their books and chronicles, “Received three hundred acres from a bad baron”; whereas the modern experts and editors record the three hundred acres and call him a good Baron.”

The spectre of tainted donations continues to loom large over modern philanthropy. In part this is due to concerns about wealth that was accrued long ago, through profits from slavery or colonialism. In recent years a growing number of universities and cultural institutions have been forced to acknowledge the problematic nature of some of their past donors (and their present wealth) due to pressure from supporters, students and the public.

This was amplified following the wave of Black Lives Matter protests around the world in 2020 sparked by the murder of George Floyd. At this point there were signs that an even more widespread historical reckoning might take place, as many organisations chose to face up to their own pasts. Whether this results in genuine longer-term change in terms of how we deal with historically tainted wealth remains to be seen.

Concerns about tainted donations are not restricted to dubious gifts from the past, of course. There are plenty of living donors whose giving continues to pose ethical issues. Most notable in this regard in recent years has been the Sackler family, whose role in creating and profiting from the US opioid epidemic – as detailed in books such as Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain – has led many cultural and higher education institutions that once benefitted from the Sacklers’ giving to declare they will no longer accept their donations; and in some cases that they will also remove the family’s name from buildings that previously bore them.

The Sacklers are far from being the only example either. In fact, if anything, tainted donation scandals are occurring with greater frequency than ever before. Perhaps this is because more scrutiny is being given to philanthropy so ethical concerns come to light more easily? Or perhaps the ethical criteria we apply have become more demanding so a greater number of cases are seen as problematic?

Either way, concerns about tainted wealth continue to pose a challenge for philanthropy.

Donors may be increasingly wary of giving (or at least doing so in an open and transparent way) if they feel as though this will put them in the firing line of attacks on how they have made their money. Conversely, cash-strapped organisations faced with ethically-questionable donations need to decide whether they can justify taking the money or should refuse it, and this involves grappling with a range of complex issues.

Does acceptance of the gift, for example, imply condoning the donor and thus risk making the recipient organisation complicit in reputation laundering? How does an organisation balance the potential long-term reputational damage of accepting a questionable gift against the definite short-term financial damage of turning it down? Does the gift come with strings attached, so that the donor is able to exert control over how it is spent; or is it entirely at arms-length?

New developments in technology may bring further challenges too. There is a growing trend towards “crypto-philanthropy”, in which people use cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin or Ethereum) to make donations. Since these cryptocurrencies are designed in part to maintain the privacy of users, charities that accept crypto donations may find it even harder to ascertain the source of the funds being given (as a number of charities have already found, to their cost).

Tainted donations and the ethical challenges they bring seem certain to remain a major issue for philanthropy in coming years.