The relationship between religion and philanthropy is deep and long-standing. For a long time the two were inextricably linked, as virtually all giving was guided by religious teaching and done via religious institutions. However, the Reformation in 15th Britain – which saw a schism between Catholicism and Protestantism following the decision of Henry VIII to leave the Church of Rome – together with the rise of a new form of secular humanism in continental Europe during the 16th century (epitomised by figures such as Erasmus) eventually paved the way for a new secular conception of philanthropy, which would be distinct from the religious almsgiving of medieval times.

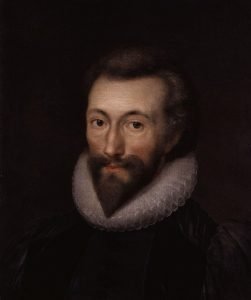

This secularisation was a very slow process, however; and religious teaching continued to play a major part in motivating and shaping philanthropy for a long time. Protestant preachers and writers in the 15th and 16th centuries, keen to find new ways to distinguish their religion, often caricatured Catholic giving as “superstitious” and derided it as inferior to their own brand of “worldly” philanthropy. The poet John Donne, for instance, claimed that:

“There have been in this kingdome, since the blessed reformation of religion, more publick charitable works perform’d, more hospitals and colleges erected and endowed in threescore, than in some hundreds of years of superstition before.”

The secularisation of philanthropy only really took root with the advent of the enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the arguments of influential thinkers like Mary Wollstonecraft, Emmanuel Kant and Thomas Paine led to the emergence of new views on the interplay of rights, responsibilities, charity and justice in our society.

The link between religious identity and philanthropy remained important for many, however. This was particularly true of minority groups, for whom systems of mutual aid and charity were often vital because they were excluded from the support that mainstream society offered. This was the case for the many dissenting groups of Protestants- including most notably, perhaps, the Quakers; whose willingness to combine commercial success with a strong habit of giving saw them produce many celebrated philanthropic families such as the Cadburys and the Rowntrees. It was also true of Britain’s Jewish community, which likewise gave rise to many significant philanthropists like Frederick David Mocatta and Baron Maurice de Hirsch.

Religion remains an important element of philanthropy to this day. Faith and religious teaching are key factors that motivate and inform the giving of donors at all levels; even if the causes they focus on and the approaches they use reflect are not always religious in themselves and reflect our more secular modern understanding of philanthropy.