We explore why “trust-based philanthropy” has gained ground as an idea, what it is framed as an alternative to, and why there is still a gap between rhetoric and practice.

13th June 2024

Over the past few weeks, one topic has dominated most of my conversations, reading and thinking about philanthropy: trust. The news that Melinda French Gates is planning to adopt a no-strings-attached approach in her post-Gates Foundation solo ventures similar to that taken by Mackenzie Scott has brought with it a new spike of interest in the whole question of “trust-based philanthropy”. At the same time, the current Summer edition of the Stanford Social Innovation Review (once very much the spiritual home of technocratic, impact-focussed philanthropy) provocatively declares on its front cover that “Strategic Philanthropy is Dead” and asks “What’s Next?” (With the obvious implication that trust-based philanthropy is a big part of the answer to that question). On a personal note, I was lucky enough to be in Ghent, Belgium to moderate one of the closing plenary sessions for the Philea Forum, where the topic for the whole conference was trust; and I also travelled to Frankfurt to take part in a workshop for grantmakers, where I gave a talk on – you guessed it – trust based grantmaking.

Trust has been a motif within a lot of debate about philanthropy and civil society in recent years, so the current wave of interest certainly hasn’t come out of nowhere. However, it does feel as though we have arrived at a moment where trust has become a particularly hot topic for the philanthro-sphere. To some extent this is a natural extension of pre-existing conversations about how and why we need to reform philanthropy; but it also reflects the fact that 2024 is a year in which a significant number of important elections are taking place across the world, against a backdrop of concerns about the potential for new technological tools to spread misinformation and polarisation, and so the question of how we develop and maintain trust feels more crucial than ever before.

When it comes to the relationship between trust and philanthropy, the issue can be parsed in many different ways, leading to a range of distinct questions. For instance:

-How do we ensure public trust in philanthropy as an idea and a sector?

-Will the apparent long-term decline in public trust in institutions across many different geographic areas have a detrimental effect on philanthropy and civil society?

-What new challenges are there in the digital world for our notions of trust and authenticity, and what does this mean for civil society organisations and funders?

-What role can philanthropy play in addressing the potential negative impacts of technology on public trust?

These are all interesting and important questions. They are not, however, what I want to talk about in this blog (although I have talked about some of them elsewhere already, and no doubt I will come back to all of them at some point). What I want to focus on here is how trust manifests within the practice of philanthropy, in terms of the relationship between funders and recipients – which is what is most often meant when references are made to “trust-based philanthropy”.

And the key question to my mind is: why is all philanthropic funding not already trust-based? One thing that has struck me about many of the conversations I have been part of over the last few weeks and months is that when the question of funders placing greater trust in recipients by doing things like shifting decision-making power, giving unrestricted funding, or modifying approaches to measurement and evaluation, there tends to be furious agreement that these are all Good Ideas. (I am, of course, wary about drawing any strong conclusions that there is broad consensus on these issues across the philanthropy world, as it may well be that the sample I am basing my inferences on is narrow and unrepresentative. However, I do genuinely feel as though I have heard a sufficient range of similar sentiments across different contexts at this point to have at least an anecdotal sense that something real is going on).

Why, then, is there still such a gap between all the warm words about trust-based philanthropy, and the reality that most grantmaking is still being done using more ‘traditional’ approaches? Are people being disingenuous, and only paying lip service to the importance of trusting relationships in the knowledge that they are unlikely to ever actually change how they do things? Or are there barriers holding people back from acting on their best intentions?

What is trust-based grantmaking?

The first thing we should do is define what we mean by “trust-based philanthropy”; but before we do that, we probably need to make sure we are confident in our understanding of what “trust” means. Which may be easier said than done, since it is definitely one of those concepts that proves stubbornly resistant to being pinned down. The Oxford English Dictionary defines at least one sense of the word “trust” as “firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something; confidence or faith in a person or thing, or in an attribute of a person or thing”. The academic Rachel Botsman, meanwhile, who has published widely on the nature of trust in the modern age, rather more pithily defines it as “a confident relationship with the unknown”. These definitions may not tell us all we need to know about trust, but they do give useful pointers to some of its key characteristics: in particular, the invocation of ‘belief’, ‘faith’, ‘confidence’ and ‘the unknown’ highlights the fact that one of the key functions of trust is enabling us to act in situations where we have imperfect or incomplete information. And, as pointed out by the historian Timothy Synder in a short video message ahead of the closing plenary at the Philea Forum, “trust” has an object – it is a relationship we have with a person or thing. So in situations where we do not have (or cannot have) all of the required information to make wholly evidence-based decisions, trust allows us instead to lean on our relationships with particular individuals or institutions to justify our decision and actions.

In the context of philanthropy, what does it mean to adopt a “trust-based approach”? One way to understand this might be to ask what the alternative is: if relationships between funders and grantees are not based on trust, then they must be based on other mechanisms that are aimed at providing a degree of certainty – such as contractual obligations, carefully-defined grant criteria, short-term funding cycles and demands for measurement and reporting. These kinds of mechanisms are taken to be characteristic of “strategic philanthropy”, which is often posed as the antithesis to trust-based philanthropy and has for a long time been the de facto norm for giving and grantmaking (particularly by institutional funders such as foundations). So at this point we need to ask why is it that strategic philanthropy came to be the dominant paradigm, and why is that paradigm now being challenged?

The History of Strategic Philanthropy

The basic idea behind strategic philanthropy – that it is the role of the funder to identify the key issues and their potential solutions, and to determine the most effective distribution of resources to achieve specific desired outcomes that are then rigorously measured – has been so pervasive within philanthropy for such a long time that it might have come to seem to some almost like an a priori truth. But like everything in philanthropy, it is in fact the product of a long history and a wide range of contextual factors, so it is worth examining that history to understand how this idea came to be so dominant and why it is now being challenged.

In their lead article on “where strategic philanthropy went wrong” for the aforementioned 2024 summer edition of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, Mark Kramer and Steve Phillips lay a large portion of the blame for the emergence of the ideal of strategic philanthropy at the feet of Andrew Carnegie. And they are certainly right to point out that Carnegie’s assertion in his hugely influential Gospel of Wealth that “the man of wealth [must become] the … agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves” seems horribly patronising and paternalistic to most modern eyes. (Indeed, whenever I have heard people in the philanthropy world approvingly citing Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth without any caveats over the years, I have tended to wonder whether it is best to assume they haven’t actually read it, or whether they just have objectionable views….?) However, I don’t think the full story we need to tell starts with Carnegie. In fact, it goes back much further than that.

This isn’t the place to go into all the details (for that, you will have to wait for the award winning 20-part Netflix documentary on the history of philanthropy that I’m sure I will get round to pitching at some point), but the key thing to note is that there is long history of people trying to make philanthropy more “rational” or “discerning” in one way or another. In many ways this reflects the fact that there is an inherent tension at the core of philanthropy; between its expression at an individual level, as voluntary acts of giving (which are driven by a wide range of factors, many of which are unconscious or irrational) and its expression at a systemic level, as a mechanism for the allocation of assets within society that sits alongside the state and the market. At this latter, macro, level there is an understandable desire to maximise ‘efficiency’ and ‘effectiveness’, by matching supply with demand and reducing wasted effort. But at the same time there is a realisation that trying to do this through coercive policymaking or legislation may be counterproductive, as it undermines the fundamentally voluntary nature of the individual acts of philanthropy that make up the whole. So instead, many have tried to square the circle by proposing ways in which the influence of the “heart” (i.e. emotion and subjective choice) on giving can be replaced by the “head” (i.e. rational, evidence-based decision making).

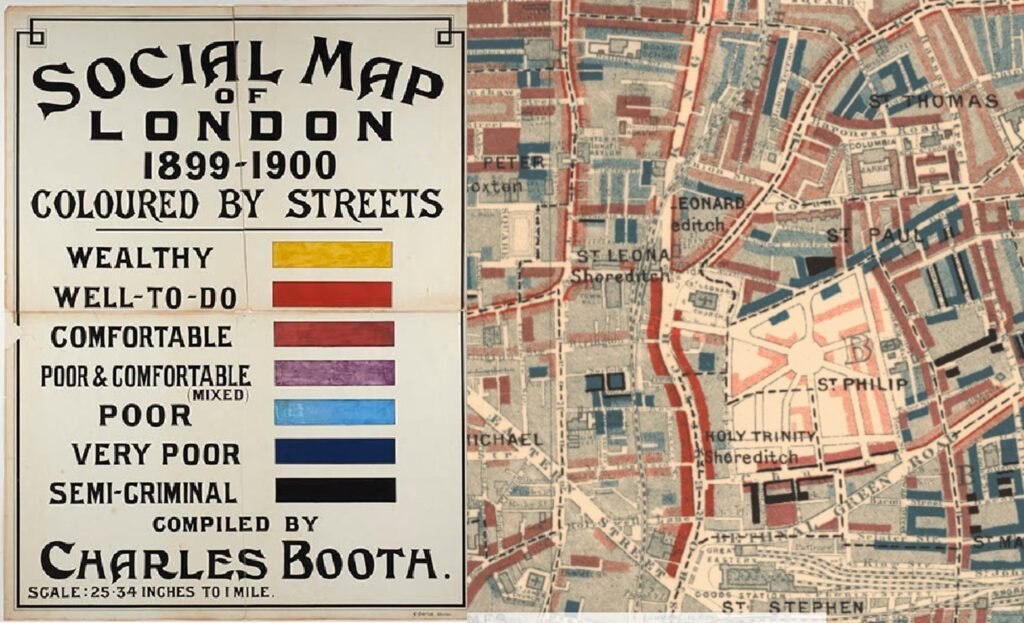

Often the desire to make giving more rational has manifested in the form of the idea that we need to be more ‘discriminating’ as donors about who are the ‘deserving’ objects of our support and who are ‘undeserving’. If you want to know more about the roots of this idea all the way back to the ancient world, and how it evolved through the middle ages, you can read all about it in a previous WPM article; but for our purposes here we can pick up the story at the Enlightenment. This was a time when many fundamental ideas about society were being reformulated according to new principles of science and rationality, so it is unsurprising that the idea of making charity more rational was an important part of the mix. The Scottish philosopher David Hume typified a common view of the time – that the impulse to give is laudable, but that it needs to be tamed – when he said:

“Giving alms to common beggars is naturally praised; because it seems to carry relief to the distressed and indigent: but when we observe the encouragement thence arising to idleness and debauchery, we regard that species of charity rather as a weakness than as a virtue.”

The important thing, for Hume and others, was that you had to find a rational way of determining which individuals or causes were “most deserving” of your giving and ensure that (as far as possible) you only gave to these and not to any others. In some cases the costs of getting it wring could be high: the city of Hamburg, for instance, introduced a law in 1788 which stipulated that people could be sent to prison for giving ‘badly’ (i.e. in an indiscriminating way) to charity. This is obviously an extreme example, but the idea that giving needed to be “discriminating” became increasingly influential throughout the 19th century into the 20th.

An important additional factor was the growing urbanisation and industrialisation of society, as it meant that the nature and scale of poverty changed, making the direct, person-to-person approach that had defined traditional almsgiving no longer feasible. Instead those who wanted to give to alleviate poverty and suffering had to find new methods, which they often did by forming new organisational entities (modelled on the recent commercial innovation of the joint stock corporation), through which multiple donors could pool resources and appoint a professional staff to manage their distribution. This new kind of “associational philanthropy”, which gave rise to what would later come to be called charitable organisations, grew exponentially throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. And this is particularly important from the point of view of our interest in trust, because it marks a point at which the nature of trust within philanthropy changed. As Rachel Botsman outlines in her recent BBC radio series The Trust Shift, in broad terms we can see trust evolving from something that only occurs at a local level (between individuals) to something that exists at a national or international level through the creation of institutions in which we can place our trust. In the case of philanthropy, this meant that donors could now choose to trust (or indeed, not to in many cases!) the charitable organisations that they supported, rather than having to relying on their own relationships of trust with individual recipients.

Bringing us back to where we started, Andrew Carnegie was obviously heavily influenced by all of this existing thinking, and was clear about his views on what he saw as the ‘evils’ of indiscriminate philanthropy, writing: “He is the only true reformer who is as careful and as anxious not to aid the unworthy as he is to aid the worthy, and, perhaps, even more so, for in almsgiving more injury is probably done by rewarding vice than by relieving virtue”. The reason this is particularly important is that through his writings on philanthropy, and through the creation of many philanthropic institutions whose approach was based on this core principle of making giving more ‘rational’ and ‘discriminating’, Carnegie has had an enormous influence on shaping a template for philanthropy in the US (and beyond) that has endured until the present day.

In practice, what it means to take a ‘rational’ or ‘strategic’ approach to giving has evolved over time, usually reflecting the logics and worldview of the dominant modes of wealth creation of a given era. The mid 20th century, for example, saw the philanthropy world adopt many of the new concepts and tools of corporate managerialism; the late 20th and early 21st century saw the embrace of the logic of finance (with the rise of “philanthrocapitalism”, and “venture philanthropy”, and the idea that giving is a form of ‘investment’ that is seeking a ‘return’); and then in recent years we have seen a growing emphasis on technological tools and the use of data as the technology industry has become the major driver of economic growth. Whilst each of these expressions of what it means to be ‘strategic’ differs to some extent, what is common to all of them is the idea that those with wealth not only have resources that can be usefully directed toward addressing society’s problems, but that the tools and worldview that have enabled them to get rich in the first place should also provide the basis for determining how their money can most effectively be given away.

Why is strategic philanthropy being challenged?

Given this long history, why is it that the paradigm of strategic philanthropy is now being challenged? (And is this in fact an entirely new development?) In part it is about changes in philanthropy practice: at the very top level, for instance, there are a growing number of elite donors who are challenging the norms of strategic philanthropy. The highest-profile example so far has been Mackenzie Scott, who has attracted a great deal of interest not just for the scale and pace of her giving, but for her no-strings-attached approach to funding the organisations she supports (and you can read more on how Scott is challenging the status quo in philanthropy in another WPM article). But there are other examples too: Leah-Hunt Hendrix, for instance, is using the wealth she has inherited from her family’s oil fortune to embrace radical causes and approaches based on principles of solidarity and community organising (for more on that, check out this other WPM article); whilst Melinda French Gates h as made it clear that in her post-Bill solo philanthropic work she will be adopting a markedly different model from the classic strategic philanthropy approach taken by the Gates Foundation.

(Image by UK Department for International Development, CC BY-SA 2.0)

These changes in practice are, of course, not happening just at the top echelons of philanthropy. There are many foundations and donors operating at a more modest (although often still significant!) level who have moved away from (or are in the process of moving away from) the strategic philanthropy paradigm. Initiatives such as the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project in the US, and IVAR’s Open and Trusting Grantmaking project in the UK are bringing together funders with a shared interest in exploring trust-based approaches, and providing them with the tools they need to made changes in practice. Further momentum for this kind of work came during the Covid-19 pandemic, as there were suddenly new and acute needs to be addressed and many funders that had been operating in traditional (e.g. programmatic, restricted) ways were forced to experiment with more flexible, trust-based approaches. For some funders this was something of a revelation, and they have subsequently been keen to explore how all or part of their work could be done in a similar way in future. (Although there are also concerns that some of the momentum may be starting to wane, and that norms and practices in grantmaking are reverting to their old defaults).

The current challenge to strategic philanthropy is also partly about rhetoric. In recent years there has been a growing wave of scrutiny and critique of philanthropy. Many of the key criticisms (e.g. that philanthropy exacerbates power imbalances, that it is anti-democratic, that it is a symptom of problematic wealth inequality rather than a solution to it, etc) are particularly aimed at a version of philanthropy that reflects the strategic paradigm (i.e. top-down, donor-driven, technocratic). As such, among those arguing for reform of philanthropy (rather than outright rejection), adoption of trust-based principles is often seen as an important part of the solution. Perhaps most striking in recent months in terms of the rhetorical shift, has been the enthusiastic embrace of trust-based philanthropy at a number of major publications that would at one time have been seen as sitting squarely on the strategic side of the fence: we have already mentioned SSIR a number of times, but earlier this year The Economist (which was the intellectual birthplace of philanthrocapitalism not that long ago) also ran a special feature on philanthropy in which it noted approvingly that “”No strings giving” is transforming philanthropy”. It is hard to know whether articles like this are merely reflecting the prevailing mood or trying to influence it, but either way it seems like a clear indicator that something is going on.

Arguments against Strategic Philanthropy

We have established that many people are pushing back on the paradigm of strategic philanthropy right now, but what is it that they actually object to? I think we can discern at least three distinct arguments.

“Strategic philanthropy doesn’t work”

The first argument levelled against strategic philanthropy, and the most fundamental one, is that it just doesn’t work. If taken on its own terms, the whole point of strategic philanthropy is that it is claimed to be the most effective means of achieving given outcomes through giving resources away. But what if that isn’t true? Kramer & Phillips argue in their leader for the summer 2024 issue of SSIR that this is precisely the case at a macro level, and that “when it comes to solving our society’s most urgent challenges… strategic philanthropy has been astonishingly ineffective”, since, they point out, “over the past four decades, US philanthropic giving has expanded exponentially, while most social or environmental problems have persisted or worsened.” One might argue that this is an unfairly high bar, as these problems are all complex and intractable, and if the claim was that strategic philanthropy could only be judged successful if it single-handedly solved these issues then I would agree. However, the question here is not whether strategic philanthropy is the solution by itself (although it is worth pointing out that some advocates for strategic philanthropy have occasionally suggested as much…); the question is whether strategic philanthropy is more effective than any other method of distributing money that we could have chosen. Particularly if these alternative methods don’t come with as much baggage. And here strategic philanthropy might have a problem: experiments in recent years with things like unconditional cash transfers and randomised grant allocation have taken various elements of the strategic philanthropy paradigm (i.e. the idea that the funder needs to choose the “best” recipients, or the idea that restrictions need to be placed on how funding can be used) and posed the question “what if we just, well… didn’t do that?” The results of these experiments so far suggest that the outcomes are at least as good if not better using these alternative approaches, which one might take as a pretty serious challenge to the principles on which strategic philanthropy stands.

“Strategic philanthropy is dehumanising”

Let’s put aside for now the question of whether strategic philanthropy works by its own measures. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t; but the argument made by some critics is that even if the approach is effective in some senses, that effectiveness comes at an unacceptable cost, because the imposition of top-down control by donors or funders is dehumanising for recipients and undermines the fundamental value of the gift relationship in building genuine human connections.

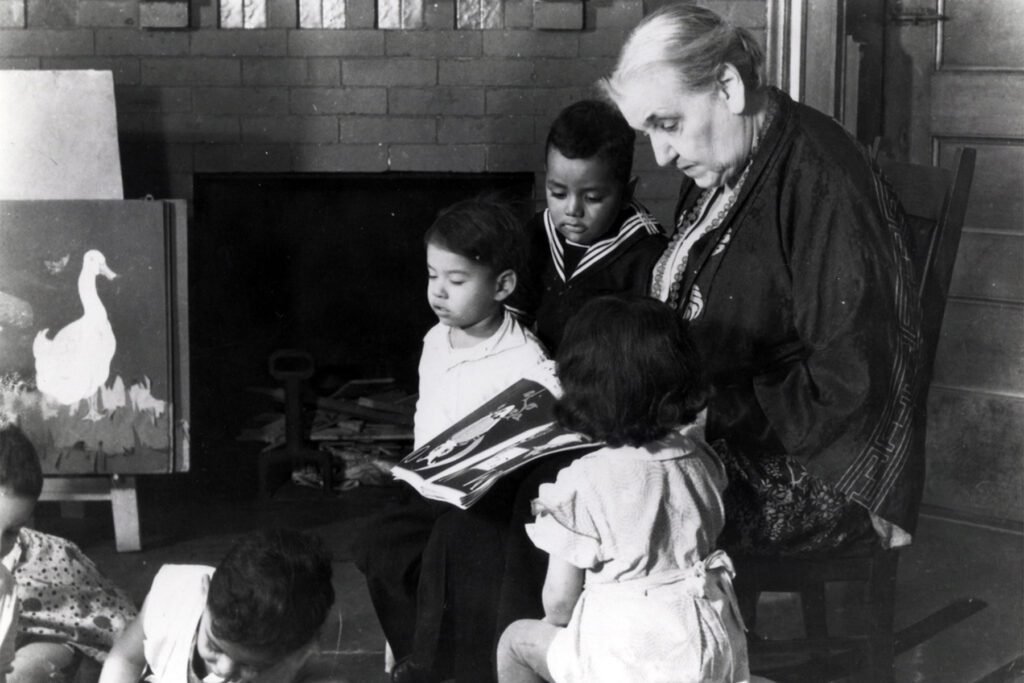

This is not a new line of argument: we saw already that there has been a long history of trying to make philanthropy more “rational”, and there has been an equally long history of pushing back on this idea. The American social reformer Jane Addams, herself a noted philanthropist (and the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize), wrote that “even those of us who feel most sorely the need of more order in altruistic effort and see the end to be desired, find something distasteful in the juxtaposition of the words “organized” and “charity”… at bottom we distrust a scheme which substitutes a theory of social conduct for the natural promptings of the heart, even although we appreciate the complexity of the situation.” The writer Ambrose Bierce, meanwhile, acknowledged that “indubitably much is wasted and some mischief done by indiscriminate giving” but argued that “there is something to be said for “undirected relief” all the same” because “it blesses not only him who receives, but him who gives”. And the philosopher George Herbert Mead argued that:

“Organized charity covers but a small part of the field within which these kindly impulses express themselves. Among our own kith and kin, among our friends, in those undertakings that seek to advance human welfare and lessen its suffering in numberless ways, in “the little nameless unremembered acts of kindness and of love,” these impulses are called out, and in few of them could we justify their exercise by a reasoned statement of consequences. Indeed, in many of them, such a rationalization of the impulse would diminish if not extinguish its worth and beauty. In kindness, the genuineness and strength of the impulse weigh heavily in our estimate of its worth and that of its author.”

Retaining human connection in giving is also important because without it an overly detached, rational approach can lead even those with the best of intentions to lose sight of the potential unintended consequences and harms of their actions. The starkest example of this can be found in the first half of the 20th century, when many progressive-minded philanthropists and funders, influenced by the application of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection to human societies, came to support various highly problematic eugenic theories as a means to address issues of ill health, poverty and disability at a population level. Some organisations which still exist today and have this in their past (like the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation) have acknowledged these elements of their history, but there is certainly further to go in addressing this difficult history as a whole. In the meantime, philanthropy’s entanglement with eugenics offers an important warning from history about what can happen when ‘rational’, society-level solutions are pursued at the cost of respect for individual human lives. (For more on the murky history of philanthropy and eugenics, read this previous WPM article).

“Strategic Philanthropy fosters injustice”

The last of the three arguments against strategic philanthropy I want to highlight is that it creates or exacerbates issues of injustice. Now, there is a long history of pointing out that charity and justice are two different things (a history that you can explore at length in a previous WPM article). From women’s rights pioneer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft’s assertion in the 18th century that “it is justice, not charity that is wanting in the world”, through to civil rights leader Dr Martin Luther King’s famous reminder that: “Philanthropy is commendable, but it must not cause the philanthropist to overlook the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary”, many writers and thinkers have been keen to point out that charity is not the same thing as justice; that charity might not be a good way of delivering justice; and that in fact, charity might actually get in the way of justice (by providing a palliative that undermines calls for more fundamental reform). Again, these arguments – whilst aimed at philanthropy as a whole – are stronger when applied to forms of philanthropy in which the donor retains a high degree of power and control; as in this case the suspicion that the giving does little to address any of the fundamental structural injustices of the status quo (and may even be acting as a form of social control) feels harder to refute.

These kinds of arguments about the need to make philanthropy more aimed towards justice are an important part of the thinking of many of the high-profile philanthropists today who are embracing trust-based approaches. They clear feel that these kinds of approaches allow for far more in the way of genuine shifts of power from donors to recipients, as well as allowing grantee organisations the freedom not just to address the symptoms of inequality and injustice, but to challenge their underlying causes.

It is worth saying that whilst there certainly seems to be a groundswell of momentum currently for radical approaches to philanthropy that place justice at their core, the idea is not in itself an entirely new one. There have long been donors who have expressed concerns that their wealth is the product of injustice and grappled with the question of how best (if at all) philanthropy can be used to address such concerns. Back in 1922, for instance, Charles Garland, inherited a million dollars from his Wall Street financier father, which he initially wanted to turn down on the grounds that he did not want to take money from “a system which starves thousands while hundreds are stuffed… which leaves a sick woman helpless and offers its services to a healthy man”, but was eventually convinced to accept in order to fund progressive causes. He did this through the “American Fund for Public Service”, a limited life foundation he established and through which he handed over the decision-making power about how the money should be used to a board of representatives of various progressive causes, explaining that:

“I feel personally that the money should be distributed as fast as it can be put into reliable hands. There is nothing that stands in the way of sensible expenditures of money so much as does the possession of too much money. And the longer you have it the harder it is to see straight. I feel that if the money is not spent now, it will be spent too much by mind and too little by heart.”

Garland is not the only person to use his inherited wealth in this way in the past either: in the 1970s George Pillsbury (an heir to the Pillsbury baking fortune) helped to found the Haymarket People’s Fund in Boston, a radical pioneer in participatory grantmaking, where communities that would traditionally have been the recipients of grants were instead given the power to decide how resources should be allocated (and which is still going strong today). In 1979 Pillsbury also helped to set up the Funding Exchange, a network of like-minded wealthy people and foundations interested in adopting a social-justice focussed approach to philanthropy, which ran until 2018. (When it closed, the Funding Exchange also published a report about its history entitled Change, Not Charity, which offers a fascinating overview of social justice philanthropy in the US over the course of four decades).

What does this mean for practice in philanthropy?

Given this theoretical and historical framing, what does the push to make philanthropy more “trust-based” actually mean for practitioners today? To my mind it is driving a number of interesting and important trends, as well as raising some challenging questions.

Core cost/Unrestricted funding:

These terms are often used as if they are interchangeable, but they probably shouldn’t be. So, I’m going to follow IVAR in taking unrestricted funding to mean funding that comes with no stipulations about how it is spent (as long as that is in line with an organisation’s mission), whilst core funding means funding that is more specifically for the purposes of supporting an organisation’s own essential running costs. (So unrestricted funding could certainly be used to pay for core costs, but it needn’t be; whilst core cost funding, conversely, can’t be used to pay for all of the things that unrestricted funding can be used for).

It has long been agreed (among civil society organisation, at least) that core funding and unrestricted funding are the holy grail when it comes to support that makes it possible to do their work most effectively. Yet at the same time, this continues to be the hardest kind of support to find. As William Beveridge noted in 1948 in his report on “Voluntary Action”: “it is particularly difficult to get money for administrative expenditure. Yet without some administrative expenditure voluntary agencies cannot be well managed”. And Warren Weaver, the mathematician who was for many years in charge of science funding for the Rockefeller Foundation, argued in his 1967 book on US Philanthropic Foundations that:

“Generally speaking, a philanthropic foundation should make grants with a minimum of strings attached. Indeed, when a grant is made to an institution or for a person of established reputation and demonstrated competence and reliability, the granting foundation should from that moment forward leave the matter in the hands of the recipient, with that minimum of fiscal control required for legal or other formal reasons.

One might say that a philanthropic foundation ought not to make a grant unless it is satisfied that both the practical management and the intellectual direction of the enterprise are competent and trustworthy and, if this is the case, why not let them alone?”

Now the eagle-eyed among you will have noticed that Weaver suggests that the key criterion for receiving core support is being “an institution or a person of established reputation and demonstrated competence and reliability”. And this hints at why, despite all the enthusiasm among recipient organisations and the often warm words from funders, core funding is far thinner on the ground that you might think: because it requires trust. Giving a person or organisation core support is a tangible gesture of trust – you are saying “here, have the money, I trust you to know how best to use it”. But, as we have seen, many of our dominant models and methods of philanthropy are not based on trust, but on control, contracts and measurement; so core funding requires a major shift of mindset.

This has been a particular issue for grassroots organisations and those doing work that might more radically challenge the status quo, as their chances of gaining the trust of donors and funders who themselves have benefitted from that status quo are generally lower than those of organisations and causes perceived as “safer”. As Robert Bothwell notes in his chapter in an edited volume on the history of philanthropy and popular movements:

“Core support can be revolutionary. Perhaps that is why core funding is much more often granted to institutions of higher education or arts and culture – which are not likely to do anything revolutionary – than to grassroots organizations in low-income neighborhoods, activist immigrant groups, or organizations of the disabled and marginalized racial/ethnic groups – which might.”

One of the main ways in which the push for trust-based philanthropy has manifested in practice so far is that there seems to be much more of a concerted effort to acknowledge these issues and to explore what is required in terms of trust between funders and grantees to make core funding the norm, rather than the exception. (For more on core cost funding, see our short WPM guide)

Long term funding:

In addition to removing any strings that might be attached to funding, another important part of the conversation about trust-based philanthropy is making this funding longer-term. The point being, that this another way in which funders can and should show trust in those they are supporting. If you think they are doing good work that is likely to contribute to achieving some outcome that you as a funder care about, then why not fund them for five (or even ten) years, rather than making them reapply for funding every year or two? (Since that creates uncertainty and additional administrative work, and doesn’t really foster much of a sense of trust).

This is particularly important when funding further “upstream” – i.e. research and policy work, advocacy or narrative building that is aimed at addressing underlying structural issues, where the outcomes may be uncertain and impossible to determine over the shorter term. Many in the US have noted that one of the real success storis in terms of long-term, trust-based funding (whether you agree with the aims or not) is to be found in the example of how conservative funders in the latter half of the 20th century up to the present day have supported efforts to shift the policy agenda to the right by funding academics, activists, think tanks and others (often on an unrestricted basis). Efforts whose impact is now being felt in multiple different ways, both politically and culturally.

Changing grant applications:

Some aspects of the trust-based philanthropy conversation are very concrete and practical: for instance, the processes and requirements funders use when it comes to grant applications. Those who are critical of current norms argue that they reinforce power imbalances, and give the impression (whether intentionally or not) of philanthropic funders as high-walled fortresses from which wary philanthropoids occasionally throw down money, rather than them being seen (and seeing themselves) as willing partners keen to provide civil society organisations with the resources they need.

To overcome these challenges, a growing number of funders are experimenting with different ways of managing grant applications. Some, for example, are now allowing non-written applications, in the form of video submissions or phone call; while others are allowing applicants to re-use applications they might have made to other funders, rather than making them produce similar-but-just-different-enough-to-require-total-rewriting ones each time (which often happens currently). None of these by themselves is going to solve the problem, admittedly; and arguably you don’t need to be an enthusiast for trust-based grantmaking to recognise that grant application processes are problematic and need reform either,

Rethinking measurement:

One of the aspects of the trust-based philanthropy conversation that I find most interesting is what it means for how we design and implement methods for measuring the effectiveness of funding. For most of the time I have been working in the philanthropy field (getting on for 20 years), the general direction of travel has been towards seeking ever more and ever better measures of impact – very much in line with the paradigm of strategic philanthropy. However, in the last couple of years there does seem to have been something of a shift back in the opposite direction; with a growing number of critics asking whether measurement has become simply another tool that allows donors and funders to exert control over those they are funding, and questioning whether we need to radically alter how we think about measurement (or, indeed, accept that there may be some things we can never measure).

This has become a crucial and contentious part of the debate about trust-based philanthropy. Critics (of whom there are plenty) claim that proponents of trust-based philanthropy want to get rid of all measurement, and sometimes seem to accuse them of wanting – in their desire to address issues about power and control – to return to some kind of prelapsarian fantasy world, in which everyone is allowed to do whatever they want without having to measure anything or be held accountable. Advocates for trust-based philanthropy understandably argue that this is a deliberate mischaracterisation, and that whilst there may be some who do genuinely believe we should have no measurement at all, this is by no means a representative view. The majority of those engaging with trust-based philanthropy, they point out, still want to measure whether what they are doing is having an effect; they just want to ensure that they do so in a way that is proportionate and which serves the needs of recipients as well as funders. (For more on current debates on impact measurement, see our short WPM guide)

Collaboration among funders:

The “trust” bit of trust-based philanthropy is often assumed to refer to the relationship between funders and grantees (as, indeed, we have largely done in this article), but that needn’t always be the case. Trust between funders is also an aspect of the conversation; which is why efforts to foster collaboration are an important part of trust-based philanthropy. From the outside, people may sometimes naively assume that philanthropic funders and civil society organisations find it easy to work together all the time because “you all share the same goals, don’t you?” However, anyone who has worked in the nonprofit sector will know that the reality is very different, and that often “egos and logos” (i.e. the desire for personal or organisational profile and acknowledgement) can present a real barrier to collaboration. To overcome these challenges, and to open up the space for more pooled funding and ecosystem-level approaches, we need to develop trusting relationships between funders, as well as between funders and grantees.

Funding grassroots organisations and social movements:

We have seen that a key driver for trust-based philanthropy is a desire to address concerns that current approaches fail to further social justice (or even actively exacerbate injustice in some cases). Trust-based approaches, it is argued, are needed in order to fund grassroots organisations and social movements; and this is a vital part of driving fundamental (and potentially radical) reform to existing systems and structures. So the relationship between philanthropic funders and social movements is an important element of this wider debate. How do we develop trust between these two groups, given that there may be significant differences between in terms of the methods they are comfortable with, the language they use, and how radical or incremental they are willing to be when it comes to addressing issues? And when funders do support social movements, how do they do it responsibly?

The power differentials in this case may be particularly large, and there is a real danger that even well-intentioned funders can do inadvertent harm, for instance by “taming” movements (i.e. diverting them away from activities and tactics that are seen as “risky”) or by causing a process of “movement capture”, in which the priorities of the movement become aligned with those of the funder as a result of their need to maintain resources. (A process that scholars like Megan Ming Francis have identified as happening many times throughout history). The interface between mainstream funders and social movements is therefore one that carries huge promise – in terms of bringing the kinds of fundamental change that many feel is now needed in society – but one that also poses significant risks. And the development of trust is a crucial part of navigating this terrain effectively.

Rehumanising philanthropy:

To some extent the elements of trust-based philanthropy we have identified so far are instrumental: they are seen as necessary and important because they allow us to achieve some other desired goal more effectively. However, it is important to highlight the fact that some who argue in favour of trust-based philanthropy do so for the more fundamental reason that they believe such approaches reflect an important aspect of giving that we have sometimes been in danger of losing: the importance of the human relationship between giver and receiver. In his 2020 opus on the history of philanthropy, Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg, Paul Vallely charts a shift from what he calls “reciprocal philanthropy” (i.e. that based on a mutual relationship of benefit between giver and receiver) to “strategic philanthropy” (i.e. that based on a top-down relationship where the giver has the power to dictate what is done and how). Vallely suggests that an important part of the prescription for overcoming recent criticisms of philanthropy is to redress this balance, and to re-emphasise the value of reciprocal philanthropy. (You can hear me talk to Paul Vallely about this on a 2020 episode of the CAF Giving Thought podcast if you are interested). More recently, in here book The Price of Humanity, author Amy Schiller argues that philanthropy has become too transactional, and that an important part of reforming it for the future will be to recognise the fundamental necessity of putting human interaction at its centre. (You can hear me talk to Amy about this earlier this year on the Philanthropisms podcast).

If you have any sympathy with these arguments (and personally I do), then the importance of trust-based philanthropy is not simply as a means of getting to some other end, but as an end in itself. Regardless of what else they achieve, connections of trust between all of the various people involved in philanthropy are important because they reflect the importance of individual human connections. And, many would argue, that is by itself hugely powerful.

So What Now?

At the end of one of these long reads, I generally like to give some thought to what it all means and what we need to do next. In this case a large part of the answer, in my opinion, is “just do more of this sort of stuff”. It should be clear to anyone reading that I think trust-based philanthropy is important, and that it poses a vital challenge to a lot of received wisdom about philanthropy, grantmaking and the role of funders. But there are also still some questions that, to my mind, we need to explore further.

Who needs to trust who?

The focus of a lot of discussion of trust based philanthropy (in this article and elsewhere) is on how we get funders to place more trust in grantees, and that is undoubtedly important. However, we should keep in mind that this is by no means the only relevant relationship of trust: what about the trust that grantees have in funders? Or the trust funders have in other funders? Or the trust civil society organisations have in each other? Or the trust that the wider public has in philanthropic funders, civil society organisations, or the whole concept of philanthropy? Or the trust that we all have, as a society, in our institutions, our leaders and each other? These are all important too, and whilst we might want to avoid complicating the conversation about trust-based philanthropy by including them under this umbrella (much as I have chosen to do here), we shouldn’t lose sight of the need to explore them elsewhere.

How do we understand success in trust-based philanthropy?

One of the things that seems slightly missing (at least to me) in the narratives about trust-based philanthropy so far is whether we need to reinterpret what “success” means in a trust-based framework. In many ways our current models for what it means to be “good” at philanthropic funding are bound up with the paradigm of strategic philanthropy: it is all about what you, as the funder, did to identify the problem and the potential solution and whether your particular intervention can be said to have measurably contributed towards a particular desired outcome being delivered. But how does that translate to the context of trust-based philanthropy? If you are giving organisations or social movements resources over a long period of time, with no stipulations about how they are spent, then does the success simply come at the point of handing over the money? Or are you still measuring the success against some other yardstick, in terms of particular outcomes? If so, are those outcomes ones that the recipient has defined for themselves (or co-created with you), or are they ones that stem from your own mission as a funder?

This is important; for one thing because there is a danger that if we judge the success of trust-based philanthropy against inappropriate measures that are based on the worldview of strategic philanthropy, we are setting it up to fail. (As a case in point, one only has to note all of the people who have looked at Mackenzie Scott’s approach and said something along the lines of “yes, but do we know yet whether it is effective…?”) For another thing, there is the matter of basic human psychology: most of us want to know in some way or other that we are doing a good job, and that includes people working in philanthropic funding organisations. If we are unable to offer a compelling narrative about what it means as a funder to do trust-based philanthropy well, my worry is that this will act as a barrier for those who would otherwise be minded to embrace the approach.

Are there limits or risks to trust-based philanthropy?

My take in this article on the potential of trust-based philanthropy has been pretty unapologetically positive. But it is important that we question whether there might be drawbacks or limitations to trust-based approaches. I should say that I don’t mean “what about the risk that a grantee doesn’t do the right thing with the money?”, as I take it that acceptance of this risk is to some extent the fundamental point of talking about trust. (If you knew for a fact that money was always going to be used effectively in the way you wanted it to be, it wouldn’t really require any trust, would it?) Rather, what I mean is that there might be situations in which it is not entirely possible or appropriate to take an entirely trust-based approach.

Is it, for instance, justifiable to give a grantee restricted funding for a relatively short period of time as a way of developing a relationship with them, with a view to then supporting them on a longer-term basis with unrestricted basis once trust has been established? Or what about a situation in which a grantee might themselves appreciate funding being restricted for certain purposes? For instances, they might need funding for capital costs, or for the costs of investing in digital transformation, or for doing a particular piece of research, and there might be concerns that if the money is not earmarked it will be diverted elsewhere. (Which obviously shouldn’t happen if everyone in that organisation is on entirely the same page, but again I come back to the point that anyone who has worked in this field will know that is not always the case…)

There may also be the risk of unintended consequences when adopting a trust-based approach. Can it, for example, potentially become exclusionary? If a funder bases all of its grantmaking on having trusting relationships, might this lead it to have a bias towards organisations it already knows (or those that its peers know and recommend)? If so, how do organisations and groups that are “outside the tent” ever get in? It is noteworthy that Mackenzie Scott, one of the most high-profile figureheads of trust-based philanthropy, has within the last year reintroduced an element of open grant applications into her approach, precisely because she and her team were aware of the dangers of becoming trapped within their own bubble. This proved to be so successful at bringing to light new projects and organisations that Scott ended up giving far more through this open call than originally intended ($640 million, when the limit had been set at $250 million), and looks set to balance her giving in future between seeking out grantees for herself and issuing open calls for applications.

Why isn’t there more trust-based philanthropy already?

And so we finally come back to the big question – the one I posed right at the start of this article: if trust-based philanthropy is so compelling, why is it that even among those who speak so warmly about it, it is not necessarily the norm in practice yet? Hopefully this article has helped to outline some of the potential barriers – which it should be clear are a mixture of historical, cultural and practical – and also pointed to some of what needs to be done to overcome them. The challenge now is just to get on and do it.